Bride price: Young South African women weigh freedom and tradition

Loading...

| DURBAN, South Africa

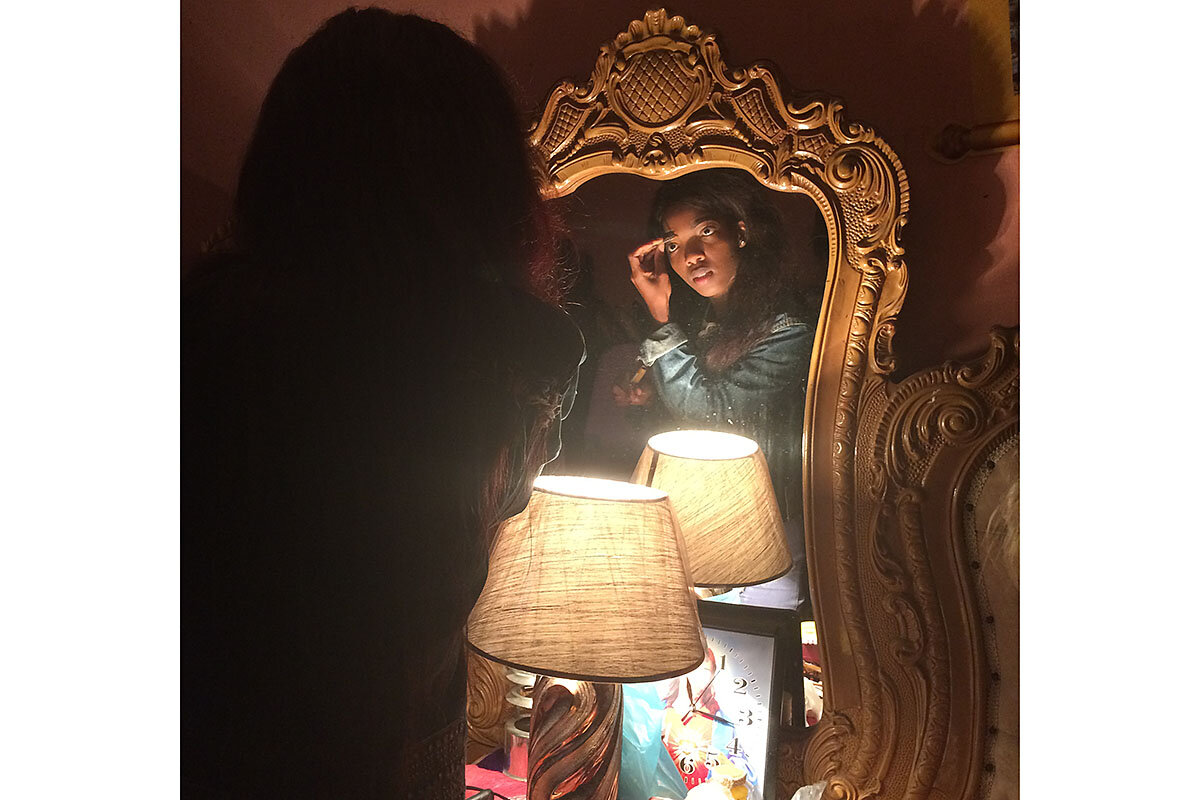

Sinegugu Sikhakhane stares at her reflection in the mirror of her bedroom, testing the makeup she will wear for her engagement party – a celebration of a proposal not made to her, or even with her knowledge.

Ms. Sikhakhane was a third-year university student when her boyfriend approached her family to ask for her hand in marriage, sealing her future with a cash payment. She was not part of the conversation.��

They wouldn’t get married for four years, when a bride price, paid in cattle, would be due, but no other man could ask to marry her.��

Why We Wrote This

Some say the practice of "lobola," or bride price, demeans women. In South Africa, young women are working to reconcile tradition and modern rights by working to find a middle ground.

“I didn’t choose – my family chose for me,” says Sikhakhane, a 22-year-old university graduate, pulling on her denim jacket and shaking loose her thick black hair.

“I love my fiancé. I do love him, but I wasn’t ready for marriage. Now because he has already gone to my family, I have no choice,” she says.��

Similar traditions, in which a groom’s family makes a payment in livestock or cash before a marriage can take place, are practiced across much of Africa, from Libya and Morocco to Zimbabwe and South Africa.��Here, it is known as lobola. The custom is part of a rich, elaborate tradition around marriage in some ethnic groups, one that has the power to forge bonds, supporters say. Critics, however, say it commoditizes women, thus disempowering them.��

Many young women say they respect the traditions of their cultures, but chafe at a transaction that treats them as a commodity and binds them to a life commitment without their consent. They’re addressing this in a variety of ways, from cohabiting to avoid traditional marriage and lobola altogether, to fighting legal battles to abolish lobola.��

“We have the power to make decisions and we respect our culture,” says Sihle Hlophe, a documentary filmmaker living in Johannesburg. “When we question our culture it doesn’t mean that we want to do away with it completely.”

Ms. Hlophe is working on a film due out in 2019, “Lobola: A Bride’s True Price,” that explores the tension women face juggling choices about their lives and the pressure of customs. It tracks her own dilemma as she navigates the expectations of community and family while pursuing personal goals – something she says creates a “huge conflict.”

Some are taking up the issue in court. In Zimbabwe, Harare lawyer Priccilar Vengesai has asked the constitutional court to abolish lobola, or if that fails, to rule that the obligation to make a lobola payment might apply to either the bride or groom’s family.��

Ms. Vengesai said the terms of her previous marriages objectified her.��

“This whole scenario reduced me to a property, whereby a price tag was put on me by my uncles, and my husband paid,” she told newspaper. “This demoralized me, and automatically subjected me to my husband’s control, since I would always feel that I was purchased.”

Ms. Vengesai is not the first to make a legal challenge. A Ugandan court rejected an appeal to ban the practice but ruled that men can’t ask for a refund in case of divorce. Zimbabwe passed a law preventing parents from accepting payment for daughters under the age of 18.��

The practice has its pluses, acknowledges Hlophe, citing the bond that is created between families through the negotiation process.��

“They have robust discussion and they bond and they eat together. They say that the people who are a part of your negotiation party are the people you turn to when you have problems, or when you know you have something to celebrate,” she says. “From that moment on, you are forever family.”

However, Hlophe, who is struggling with whether to consent to a lobola arrangement, or press her future husband for a civil marriage, dislikes that the bride price today is often paid in cash rather than in cattle.

“Cattle is a social currency,” she says, and it has symbolic value in traditional society. “Now in some instances lobola has become largely about money, and how much the bride is worth. I don’t want to be commoditized.”

In a contemporary urban setting, it’s not always realistic to negotiate in terms of cattle. Entrepreneurs have developed apps to calculate the cash equivalent of the cattle price, allowing users to adjust for factors such as education, virginity, and skills. A price of 11 cows, or about $7,000, is considered fair for someone who has finished school and is a virgin, according to the Lobola Calculator app, which was created as a joke but is used by some men to estimate an offer. That’s the price Sikhakhane’s boyfriend agreed to pay her family.

Despite being conflicted about the custom, Sikhakhane says lobola is fair compensation for what her family invested in her. She lives in her mother’s house, and although she is in her mid-20s, she obeys her mother’s decisions.��

“Because I’m still like a child under my mom’s hand and she has sacrificed a lot for me, when I get married the responsibility goes to my husband or my future husband,” she says. “So therefore he needs to pay my mom for all the money she was using sending me to school, clothing me, and feeding me.”

To skirt lobola altogether, young couples are increasingly choosing to cohabit instead of tying the knot, according to a 2011 Witwatersrand University in KwaZulu-Natal province by researchers Dorrit Posel and Stephanie Rudwick.

Half of respondents who were never married cited lobola as the main reason for not marrying, according to the study. Almost all respondents cited the cost of lobola as a concern.

Many men consider their ability to pay a mark of manhood and proof of their ability to provide for a family, however. Those who avoid it may not be recognized as properly married by their communities.

“It is a rite of passage for him in becoming a man in his family, and in my family he might not be considered as really married to me if he doesn’t do it,” says Hlophe.��

The practice puts pressure on women, too. Payment of lobola can affect the power relationship in a marriage, remove decision-making power from women, and increase the risk of domestic violence, says Nizipho Mvune, a doctoral student in gender studies at KwaZulu-Natal University in South Africa.��

“Research suggests that some men become violent when they have reduced economic power, and when they finally pay lobola, they are in a position to call the shots and dictate the terms of relationships,” says Ms. Mvune.��

In Zimbabwe, researchers from the Gender Studies Department of Midlands State University interviewed dozens of people affected by domestic violence. The found that 80 percent of them said ���Dz��DZ�����exacerbated violence based on gender.

Despite the challenges, tradition often reigns. Sikhakhane says she has a duty to her family customs, and a duty to show respect for the ancestors.��

“If you believe in them, then you do all the stuff that needs to be done,” she says. “Some people think, let me just do it for the sake of my family.”

This reporting was supported by Round Earth Media and the SIT study abroad program.��