Sacred spaces: Church buildings repurposed as community hubs

Loading...

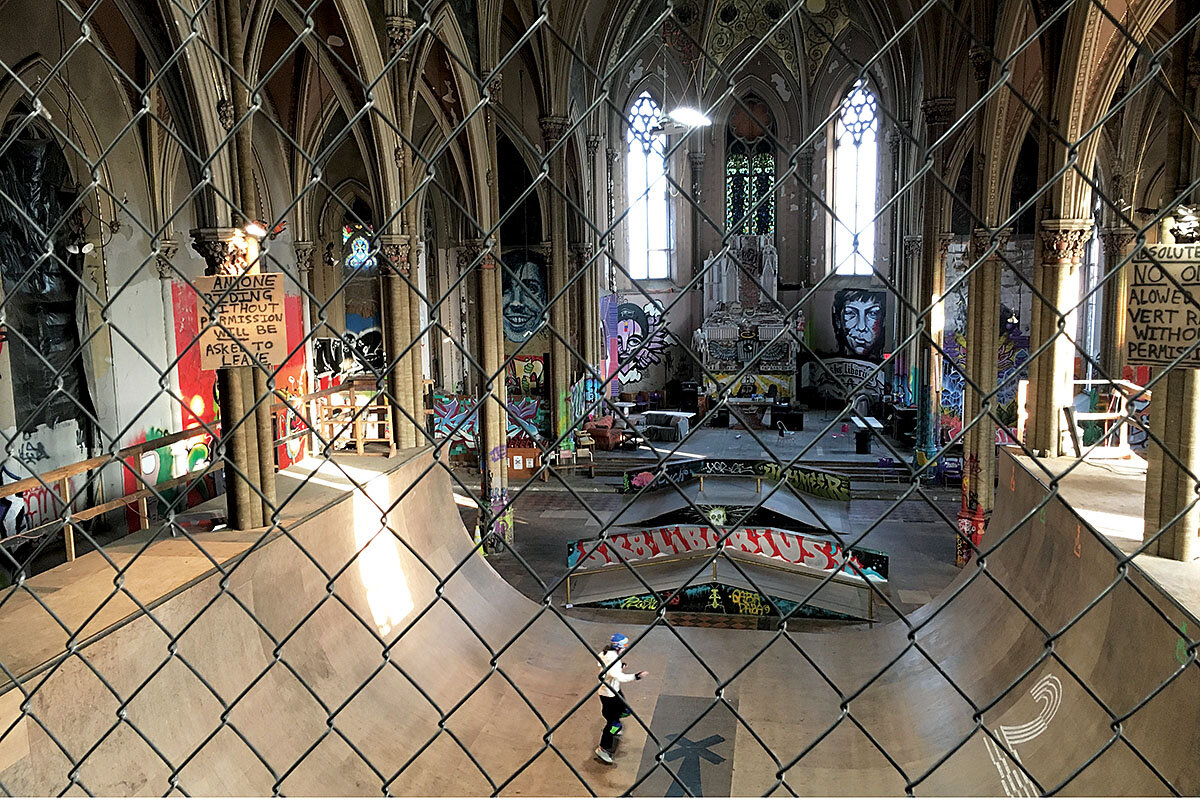

| St. Louis

Victoria Stadnik glides on roller skates down one side of a wooden halfpipe decorated in neon spray paint. Light pours in through stained-glass windows, catching her body as she rotates through the air in the nave of what used to be St. Liborius Catholic Church.Őż

After the church shut down in 1992, the building served briefly as a homeless shelter. Now, St. Liborius is better known as Sk8 Liborius ‚Äď a skate park in use informally for a decade, with plans to open officially in three years.

St. Liborius is one of hundreds of churches across the United States beginning a second life. As congregations dwindle ‚Äď only 47% of American adults reported membership in a religious organization in 2020, down from 70% in 1999 according to a ‚Äď churches are closing doors and changing hands. Developers have jumped at the chance to transform the consecrated spaces into luxury condos, cafes, mansions ‚Äď even a .Őż

Why We Wrote This

As churches close across the U.S., is their role in bringing people together being lost as well? In three cities, communities are repurposing church buildings as a way of ministering to new ‚Äúcongregations.‚ÄĚ

For some, the trend brings with it a sense of dismay.Őż

‚ÄúCongregations are the major community hubs,‚ÄĚ says Ram Cnaan, director of the Program for Religion and Social Policy Research at the University of Pennsylvania. ‚ÄúAnd I‚Äôm talking as a person who is not spiritual, who does not believe in any God, just as a social scientist. Those congregations are the fabric of our society.‚ÄĚ

But in some cities, residents are breathing new life into sacred spaces by giving fresh thought to what it means to serve, and who can constitute a congregation. Groups in St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Hallowell, Maine, are finding that one fundamental purpose of church ‚Äď community uplift ‚Äď can take many forms.Őż

‚ÄúThese places are very powerful links to the history and the evolution of our neighborhoods,‚ÄĚ says Bob Jaeger, president of Partners for Sacred Places, based in Philadelphia. Even though a church ‚Äúmay need repair, even though it may be empty, ... it‚Äôs a bundle of assets. It‚Äôs a bundle of opportunities.‚ÄĚ

For Ms. Stadnik, the skate church offers more than an adrenaline rush.Őż

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs hard to make friends as an adult,‚ÄĚ says Ms. Stadnik, who moved to St. Louis with few connections, as she catches her breath from her halfpipe run. But at Sk8 Liborius, ‚Äúit feels like I unlocked the secret.‚ÄĚ

Falling, then getting up

When Dave Blum, co-owner of¬†, speaks about his plans for the church, his voice echoes out across the sanctuary, ringing with the hope and certainty of a sermon. His team is creating not only a skate park but also an urban art studio where local artists can display and sell their work and children can learn skills ranging from metalworking to photography.Őż¬†

In every empty nook and cranny, he sees the potential to support a new congregation: underserved urban youth. He hopes skateboarding will get kids in the door ‚Äď where vital lessons await.Őż

Skating is about learning how to get up when you fall, both physically and mentally, says Joss Hay, another co-owner. If your friends fall, ‚ÄúYou don‚Äôt tell them to give up. You‚Äôre always lifting them up.‚ÄĚ

The church was completed in 1889, and after years of neglect, it has a long way to go before it can pass an inspection and be formally opened to the public. Emergency exits, bathrooms, window repair, plumbing, electricity, and heat are just a few of the items on a to-do list of fixes estimated at $1 million. But donations are pouring in from supporters, and local skaters like Ms. Stadnik, who also works as a skating coach, spend weekends helping with repair work.

‚ÄúA whole community came together to build these structures because it was important to them. And now, what we‚Äôre trying to do is have a whole community come together to maintain this structure,‚ÄĚ says Mr. Blum.Őż

‚ÄúBecoming America together‚ÄĚ

Welcoming newcomers into the fold is another function churches often fulfill. In Maine, a local nonprofit is continuing that mission by turning a former holy space into a home and community center.

Ali Al Braihi and Mohammed Abdalnabi came to the U.S. as refugees because war ‚Äď in Iraq for the first and Syria for the second ‚Äď made staying home impossible. Their journeys were different, but their families both ended up in Hallowell, Maine. Housing was limited, says Mr. Abdalnabi, and squeezing all nine members of his family into a two-bedroom apartment was ‚Äúrough.‚Ä̬†Mr. Al Braihi had the same difficulty.

Now, the 18 people that make up both families live in what used to be St. Matthew‚Äôs Episcopal Church, a classic white, wooden structure in Hallowell‚Äôs small downtown.Őż

‚ÄúWhat I feel is fortunate and thankful,‚ÄĚ says Mr. Al Braihi, now a college student. His family is Muslim, but he says he appreciates the sacredness of his new home and is just happy to finally have enough space to study.Őż

After closing last summer, St. Matthew’s offered the building to Capital Area New Mainers Project (CANMP), which supports the growing number of refugees and other immigrants in the area.

The congregation chose CANMP because it ‚Äúfelt like we would be carrying on the mission,‚ÄĚ says Chris Myers Asch, CANMP‚Äôs co-founder and executive director. ‚ÄúWe take that responsibility very seriously. It‚Äôs hallowed ground.‚Ä̬†

Mr. Myers Asch and his team of volunteers are currently renovating the sanctuary to create the Hallowell Multicultural Center. When it‚Äôs ready, anyone in the community will be able to host events: dinners, talks, movie screenings, weddings ‚Äď whatever brings people of different backgrounds together.

‚ÄúWe see it as a wonderful space to bring cultures together, to learn from each other, to share stories with each other, to share food, break bread, and really build community,‚ÄĚ says Mr. Myers Asch. It‚Äôs a place, he says, ‚Äúwhere we can celebrate becoming America together, bringing the newest Americans into the fold.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúA labor of love‚ÄĚ

Further down the East Coast, in a church turned recreation center, there‚Äôs a different type of culture unifying the community ‚Äď sports.Őż

When Coach Curt De Veaux discovered that Our Lady of Hope, a Catholic church in a low-income neighborhood of Philadelphia, had sat vacant for 15 years, his wheels started turning.Őż

After nine years as a basketball coach, he understood the power of sports to transform individuals. So he partnered with a local organization to purchase the space and began renovations to turn the church into a youth recreation center.Őż

‚ÄúA lot of kids in the area don‚Äôt have an outlet, or things to do,‚ÄĚ he says.Őż

¬†now offers basketball, volleyball, indoor soccer, lacrosse, spinning bikes, and other types of training at low to no cost to neighborhood youth.Őż

‚ÄúThere are just so many life lessons that you can help a young person navigate,‚ÄĚ says Mr. De Veaux. ‚ÄúI always tell the parents, ‚ÄėIt looks like sports, but it‚Äôs really life,‚Äô whether it‚Äôs emotional control or learning how to work with others, how to respect rules, how to compete, or practice makes perfect.‚ÄĚ

At the end of the day, Mr. De Veaux‚Äôs goal is for the church to continue to be a gift to the neighborhood. Beyond his work at the youth center, he has also organized drives for coats, school uniforms, and sports-related toys.Őż

‚ÄúEvery time I go there, I come in with a list of things I need to get done, and I come out and my list is always longer than when I went in,‚ÄĚ adds Mr. De Veaux, who says it‚Äôs taken plenty of resources, energy, and anguish to stop roof leaks, wrangle the heating system, and bring the church up to standards.Őż

‚ÄúBut it really is a labor of love.‚ÄĚ