‘Lawfare’ hits new levels, as Trump pursues those who pursued him

Loading...

| Washington

On Day 1 of his second term, President Donald Trump signed an executive order called “Ending the Weaponization of the Federal Government.”

Among its provisions, instructed both the U.S. attorney general and director of national intelligence to review the activities of their agencies and recommend “appropriate remedial actions.”

Ever since, President Trump has used the vast power at his disposal to go after people and institutions he says have done him wrong. Not since Richard Nixon’s infamous “enemies list” more than a half-century ago has a U.S. chief executive so aggressively pursued a campaign of retribution.

Why We Wrote This

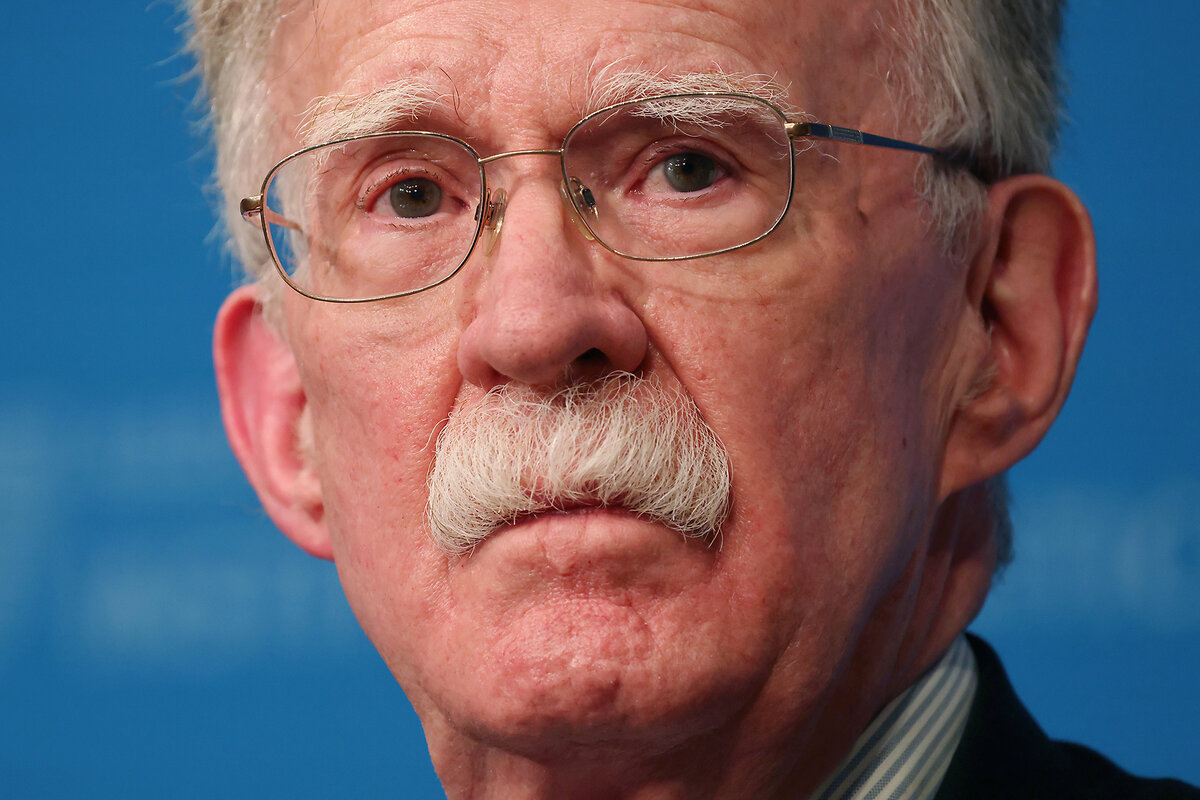

Thursday’s indictment of former national security adviser John Bolton is the latest example of the Trump Justice Department going after people President Donald Trump says have done him wrong.

Thursday’s indictment of John Bolton, Mr. Trump’s former national security adviser, along with the recent indictments of former FBI Director James Comey and current New York Attorney General Letitia James are just the start, the president himself has made clear.

Mr. Trump has taken unprecedented steps to weaponize the federal government in the name of addressing what was, in his and many Republicans’ view, the weaponization of the justice system against him during the last two Democratic administrations. That includes the end of the Obama presidency, when Mr. Trump burst onto the political scene and the FBI investigated potential ties between his campaign and the Russian government.

Whether the Democrats in fact engaged in “weaponization” is very much open to interpretation. The president’s supporters say federal and state investigations into Mr. Trump’s actions were overdone and persecutory. Mr. Trump was criminally indicted four times – twice federally and twice at the state level – and convicted once. He also faced civil suits.

Democrats and many legal experts maintain that the Justice Department under both the Obama and Biden administrations operated independently from the White House, unlike now. (Indeed, the Biden DOJ investigated and prosecuted the president’s own son.) They say investigations like the Trump-Russia probe represented necessary due diligence in the name of protecting national security or even democracy itself – and had the government not pursued them, it would have been a miscarriage of justice.

The legal cases against Mr. Trump all involved evidence, to different degrees, suggesting potential crimes. Mr. Trump’s phone call to Georgia’s secretary of state aimed at overturning the outcome of the 2020 election is a case in point. The current administration’s cases against Mr. Trump’s avowed enemies have mostly been framed by the president himself as consequences for what he labels politically motivated prosecutions.

Still, wittingly or not, by aggressively investigating Mr. Trump – be it the 2022 raid on Mar-a-Lago in search of classified documents or alleged Trump-Russia ties during the 2016 campaign or the Trump-inspired riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 – Democrats did incentivize Mr. Trump and his team to pursue retribution, some analysts say.

“The Democrats absolutely opened a door very wide that you cannot close when you leave office,” says Ron Chapman, a federal criminal defense attorney.

The federal indictment of Attorney General James, a Democrat, over alleged mortgage fraud, is a prime example. In 2022, Ms. James filed a civil lawsuit against Mr. Trump and business associates, alleging fraud in exaggerating the value of Trump properties. They were found guilty, and ordered to pay a penalty of more than $360 million. An appeals court later vacated the penalty; Mr. Trump and company are appealing the guilty verdict.

Ms. James’ long-stated goal had been to prosecute Mr. Trump. During her 2018 campaign for New York attorney general, she pledged to and “hold those in power accountable.” Now under indictment herself, Ms. James is not backing down. Campaigning with New York Democratic mayoral nominee Zohran Mamdani on Monday, she went after Mr. Trump, though not by name.

“Powerful voices,” , are trying to “weaponize justice for political gain.”

Trump making public calls for prosecutions

The lawfare in recent weeks has been intense. Last month, Mr. Trump expressed frustration with U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi in a social media post – and – over delayed action against Mr. Comey, Ms. James, and California Democratic Sen. Adam Schiff.

Other former and current top officials under investigation, if not potential indictment, include former CIA Director John Brennan; former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper; former special counsel Jack Smith; and Lisa Cook, a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

On Wednesday, Mr. Trump named additional legal targets during an Oval Office media availability – saying that Andrew Weissmann (former general counsel at the FBI) and Lisa Monaco (former deputy attorney general) should be investigated along with Mr. Smith, whom he called “deranged” and a “criminal.” The president was flanked by Ms. Bondi and FBI Director Kash Patel.

“I’m the one that had to suffer through [investigations] and ultimately win,” Mr. Trump said. “But what they did was criminal.”

Mr. Bolton was indicted on Thursday on 18 counts involving mishandling of classified information.¬Ý, he was accused of sending ‚Äúdiary‚Äù notes by email on his activities as national security adviser, with some of the information he sent labeled top secret. The emails were later hacked by someone with an Iranian government connection, according to the indictment.

Mr. Trump and Mr. Bolton had a tense relationship during the latter’s 17 months as national security adviser during Mr. Trump’s first term. Mr. Bolton’s memoir, “The Room Where It Happened,” and his public criticism of the president haven’t helped. FBI agents raided Mr. Bolton’s home and office in August in search of classified documents.

The raid on Mr. Bolton’s properties echoed the one on Mr. Trump’s Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago. It also contrasted with the fact that former President Joe Biden was never charged for keeping classified documents in his residence near Wilmington, Delaware, dating from his time as vice president and, before that, a senator. A key difference is that Mr. Biden allowed federal agents to search his property, while Mr. Trump resisted such efforts before the predawn raid.

Mr. Comey was indicted on Sept. 25 on two charges – making a false statement and obstructing a congressional proceeding. Those charges stem from a 2020 Senate hearing on FBI investigations into two matters: Russian interference in the 2016 election and Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server.

At Mr. Comey’s arraignment on Oct. 8, his lawyer called the prosecution “vindictive” and “selective,” and said he would move to dismiss the case.

When the previous U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, Erik Siebert – a Trump appointee – refused to seek a Comey indictment, Mr. Trump pressured him to resign. The interim U.S. attorney, Lindsey Halligan, a former personal lawyer of Mr. Trump’s who had no previous experience as a prosecutor, obliged in bringing the case over the objections of other prosecutors.

Experts on the federal judiciary see a major breach in the norms of how government is supposed to work.

“We’ve just crossed a Rubicon here,” says Mary McCord, executive director of the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown University.

Ever since the Nixon Watergate scandal of the early 1970s, “it has been a priority of both the Department of Justice and the White House to preserve independence” between the two, says Ms. McCord, former chief of the criminal division in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia.

The purpose of that separation, she says, was to prevent a perception by the American people of the Justice Department as “just simply being a tool for the president’s personal political use.”

Now, that separation appears to be gone.

David Sklansky, a law professor at Stanford University, argues that to describe what the Justice Department is doing as “fighting weaponization” is “Orwellian in its misuse of language.”

“You can’t say, ‘I’m all about fighting weaponization’ and in the same breath say, ‘I insist on retribution, I insist that the Department of Justice go after my enemies,’ which is what Trump has done.”

“Norms are not good enough anymore”

Republicans have been gearing up for this fight since long before Mr. Trump retook the White House. In the previous Congress, a House Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government spent two years investigating “the Biden-Harris administration’s weaponized federal government” and in December, issued . A focus was alleged government efforts to censor speech by “Big Tech.”

On Inauguration Day, in addition to signing the “anti-weaponization” order, Mr. Trump also issued a blanket pardon for the nearly 1,600 people convicted or awaiting trial or sentencing for their participation in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol in support of Mr. Trump’s false claim that the 2020 election was stolen.

Revelations about the Jan. 6 investigations continue to drive GOP ire. Last week, Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, shared a document showing the cellphone data (but not the content) of nine congressional Republicans around the time of the riot. Senator Grassley says that the analysis violated the lawmakers’ privacy rights.

The phone data was gathered in 2023 as part of the FBI’s “Arctic Frost” investigation, which informed the criminal case against Mr. Trump over his role on Jan. 6 handled by Mr. Smith – the former special counsel who now faces potential indictment himself. (Mr. Smith also handled the case involving Mr. Trump’s possession of classified documents after leaving office.) The Justice Department is investigating Mr. Smith for possible violations of a law forbidding federal employees from engaging in political activities.

In a recent interview at a forum in London, Mr. Smith dismissed allegations of politicization in the two cases.

“The idea that politics would play a role in big cases like this, it’s absolutely ludicrous and it’s totally contrary to my experience as a prosecutor,” Mr. Smith said in a discussion with , the former FBI counsel whom Mr. Trump also called to prosecute. Mr. Weissmann was a lead investigator in special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. election and allegations of Trump-Russia collusion. The Mueller report, which Mr. Weissmann helped author, found no evidence of collusion.

Historian Barbara Perry notes that after the Watergate-era “Saturday Night Massacre” – the resignation of senior government officials after Nixon fired special prosecutor Archibald Cox – Congress passed legislation aimed at insulating the Justice Department from politics: the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, the Ethics in Government Act, and the Inspector General Act.

Professor Perry, co-director of the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, also cites the words of Mr. Cox himself: The attorney general “will likely be a political ally of the president, but he is not a servant,” Mr. Cox said in 1973. “What distinguishes between the two is the ethical obligation to apply the law in a fair, even-handed, and disinterested way.”

Today, Ms. Perry says, “all of that is blown away. Norms are not good enough anymore.”