In race for president, Gen Xers are finding reality bites

Loading...

You remember Generation X. Or maybe you donโt. Itโs not your fault. History has more or less ignored my cohort since the oldest among us began turning 30 about a quarter-century ago, as if we exist but donโt much matter. Sort of like MTV.

Decisive proof of our irrelevance has arrived with the 2020 presidential race. Five of the 12 candidates who qualified for Tuesdayโs fourth Democratic debate represent Gen X. Yet their combined barely crack double digits. In appearance and ambition, they defy the enduring image of Xers as flannel-clad slackers. But in performance, theyโre still slouching toward nowhere.

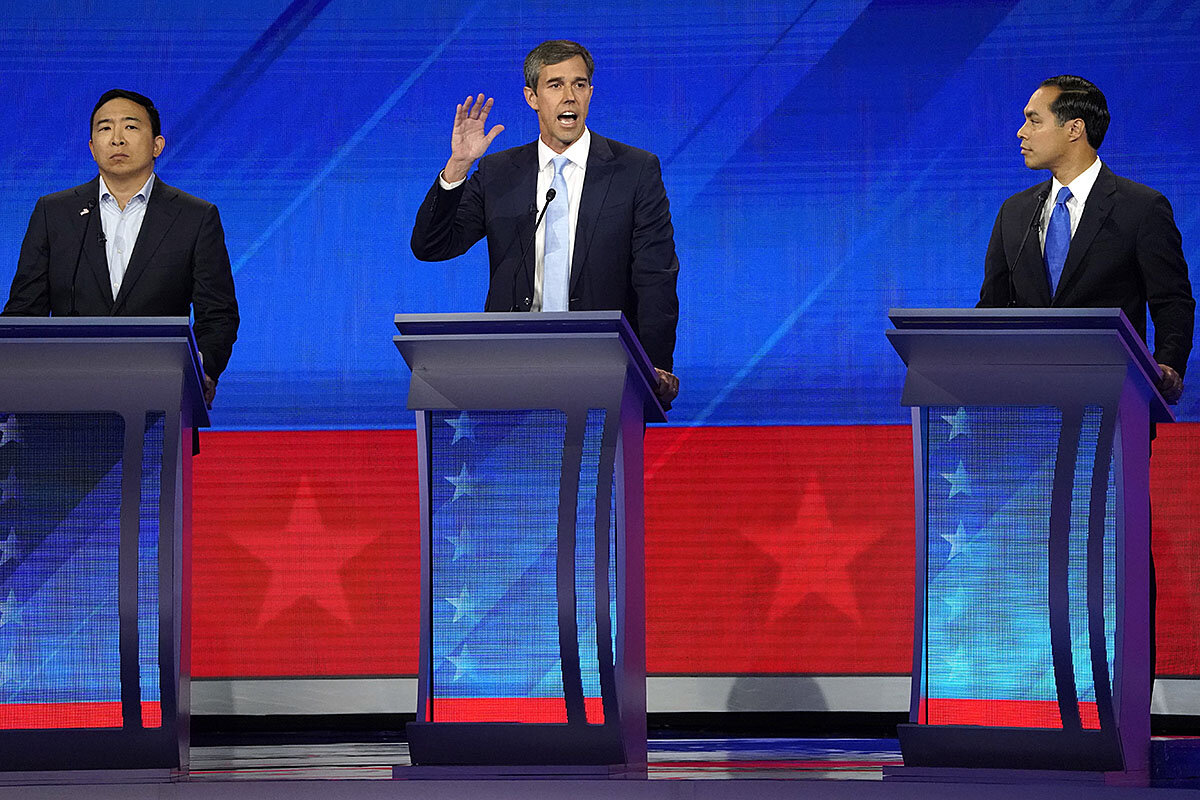

Considering our age, this decade should be the political prime of Generation X, typically defined as those born from 1965 to 1980 or sometimes 1961 to 1981. At least we showed up for the 2020 campaign โ give us that much. Under the broader time frame, 14 Democratic candidates from this cycle count as Xers, including the quintet who will take part in tonightโs debate: Cory Booker, Julian Castro, Kamala Harris, Beto OโRourke, and Andrew Yang.

Why We Wrote This

The forgotten cohort between baby boomers and millennials is fielding a number of Democratic candidates for president. But like the authorโs generation as a whole, theyโre being upstaged by those older and younger than they are.

But even with a critical mass in the field this time around โ after Gen X Sens. Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio failed to win the Republican nomination in 2016 โ our generation is finding itself upstaged once again by our elders and juniors.

Among the five leading Democratic candidates, former Vice President Joe Biden and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders hail from the silent generation; Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren belongs to the baby boomers; and millennials claim Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana. The lone Xer is Senator Harris, whose support latelyย even in her home state of California.

In many respects, Gen Xโs meager showing seems fitting, given our status as the overlooked middle child of generations. A smaller cohort wedged between the behemoths of the baby boomers and millennials, we lack their collective self-esteem โ or self-regard, depending on your view. If boomers are the Me Generation and millennials are Generation Me, Xers could be dubbed Generation Meh.

Our ambivalence about political life persists into middle age. It isnโt that our for apathy prevents us from voting; Generation X turns up at the polls in . But the futile 2016 bids of Senators Cruz and Rubio and the floundering of this yearโs Gen X candidates suggest doubts about the Xer brand among voters in our own generation as much as any other.

A possible reason for the muted support arises from the riddle of self-identity that shadows Gen X. In algebra, โxโ is the unknown variable โ and from the start, uncertainty marked our generation.

We grew up as the countryโs divorce and violent crime rates soared and the AIDS epidemic emerged and spread. The savings and loan crisis erupted, the real estate market collapsed, and the economy fell into a recession in the early 1990s. All the while, a bipartisan torrent of corruption poured forth from Washington, ranging from the Iran-Contra affair and the Keating Five to the House Post Office scandal and President Bill Clintonโs impeachment.

The venality and vice in D.C. sowed a mistrust of politicians and politics in Generation X. As we flailed in an economy weakened, in part, by the avarice of elected officials, the idea of one day seeking office held little allure. We were unsure of what we wanted but knew it wasnโt that. Why devote our lives to perpetuating deception?

The Gen X candidate who most embodies that ambivalence is Mr. OโRourke, the former congressman and punk rocker from El Paso, Texas. Last year, seeking to unseat Senator Cruz, a fellow Texan and Xer, he ran a kind of anti-campaign that drew donations from across the country and captivated the national media. Beyond his skateboarding skills and sweat-stained shirts, he displayed a disarming willingness to admit he didnโt possess all the answers.

Mr. OโRourkeโs aversion to polished assuredness nearly carried him to an upset. But the same quality hobbled him on the national stage early in the presidential race. His conflicted journey of self-discovery made him appear indecisive and out of his depth, as if forever trapped in the parallel Gen X world of โReality Bites.โ

More recently, following a mass shooting in El Paso, he has altered his public persona, echoing the raw, sometimes profane anger of gun control supporters and calling for a ban on semiautomatic rifles. Pundits have talked about Mr. OโRourke and his campaign gaining clarity, yet he continues to lag in the polls. His message has found shape but he remains indistinct.

Meanwhile, Senator Harris, the leading Gen X candidate, has proven unable to solve the puzzle of her ambiguity, even after serving 15 years in various political offices. In a recent , she mused out loud about her inability to define herself to voters. โThe challenge is, I think, people rightly want to have a sense of who somebody is,โ she told the magazine. โIโve been thinking a lot about it recently, โcause I know I need to frame it.โ

Judging from her sinking poll numbers, voters appear disinclined to trust a candidate who still struggles to โframeโ her identity in her mid-50s. One trait shared by the other four top Democratic contenders is persuasive self-conviction. They have figured themselves out. Nobody wants a question mark for president, not even Xers.

Then again, perhaps Senator Harris simply reflects the lasting identity crisis that afflicts Generation X as a whole. a few years ago revealed that only 41% of Xers associate as part of their cohort. The rest identify as baby boomers, millennials, or nothing at all.

If generational vagueness, coupled with a long-held suspicion of politics, keeps Gen X from ever winning the White House,ย we would make history in absentia โ an apt capstone for a cohort that embraced irony as a lifestyle. The latest polls show that many Xers find older or younger candidates more appealing than those from our own generation. In the end, maybe the politicians most like us are the ones we trust the least.