‘You have a right to an attorney.’ Massachusetts bar strike and the Sixth Amendment.

Loading...

| Boston

At the beginning of this year, the phrase “constitutional crisis” was everywhere. Was America heading for one? When would we know if we were in one?

This summer, residents of one state arguably have been embroiled in one, so quietly that most people haven’t noticed. And it’s a state that has been widely viewed as a model for the Sixth Amendment. That’s the one that promises a right to counsel, as in “you have a right to an attorney. If you cannot afford one, one will be appointed for you.”

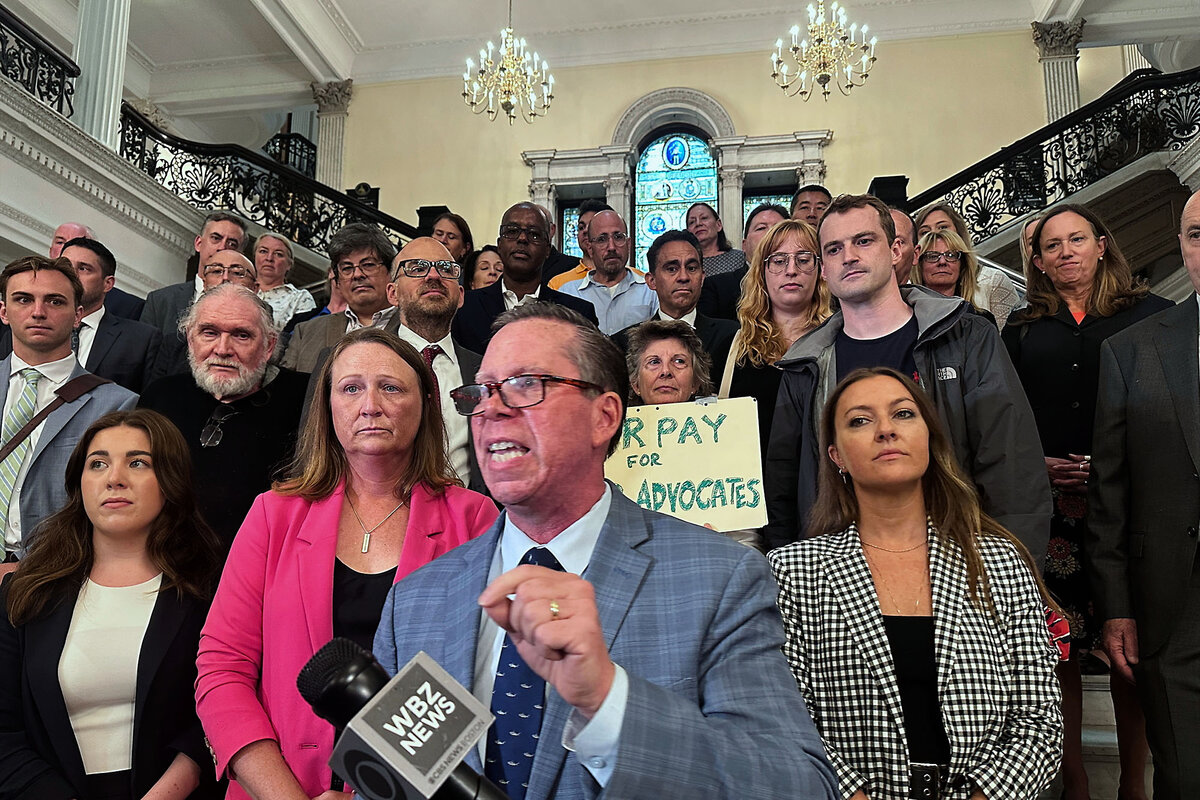

The vast majority of criminal defendants in Massachusetts rely on bar advocates – private attorneys contracted with the courts – for their constitutional right to counsel. Since May, those lawyers have refused to take new cases, staging a work stoppage to press lawmakers for higher wages.

Why We Wrote This

Sixty years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries” in Gideon v. Wainwright. The ruling was largely an unfunded mandate, which left the responsibility for representation to states. Massachusetts stands as both a model and a cautionary tale.

“It’s not a strike; it’s a constitutional reckoning,” says Bill Lane, a criminal defense attorney in Greenfield and former Boston public defender. He became a bar advocate in 2023.

“The wages are so low, there’s no reason for anyone to get into this job,” he says. “The survivability of the bar advocate system is really at stake here.”

The effects have not just been theoretical. Hundreds of criminal defendants have had their¬Ý because there weren‚Äôt enough lawyers to represent them.

Sixty years ago, the United States Supreme Court ruled that “lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries” in Gideon v. Wainwright. However, the ruling was largely an unfunded mandate, which left the responsibility to states to figure out implementation, funding, and oversight. Massachusetts stands as both a model and a cautionary tale.

This summer, the State Legislature acted swiftly, but a deeper question remains: Can states build systems strong enough to fully uphold the Sixth Amendment?

When a $10 an hour raise isn’t enough

As of August, Massachusetts bar advocates earn $75 an hour for district court cases. That’s a $10 an hour raise, with more coming next year. But bar advocates say it’s still paltry compared with nearby states like Maine, which pays $150 an hour, and Rhode Island, which pays $112 hourly for indigent defendants.

The work stoppage has led to more than , including some for violent crimes such as domestic abuse and assaulting a police officer. Since May 27, in district and municipal courts.

The bar strike raises questions about how much states should rely on private lawyers to provide the constitutional right to counsel for those who cannot afford a lawyer, called indigent defense.

Every state relies on a mix of public defenders, who are state employees, and court-appointed private lawyers to provide the right to counsel. But only three states – Maine, North Dakota, and Massachusetts – rely on private attorneys for more than 60% of indigent cases.

Massachusetts tops them all, with bar advocates handling about 80% of indigent defendants. That heavy reliance may be the system’s weak point, says Eve Brensike Primus, director of the Public Defender Training Institute at the University of Michigan Law School.

“If private lawyers handle 80% of indigent defense cases, and indigent defendants make up the vast majority of the criminal docket, it’s kind of a recipe for a crisis,” says Ms. Primus, who says low pay can also lead to “real differences in the quality of representation.” “If you don’t want to be susceptible to these kinds of problems, in the long term, you do need to have a more robust role for fully employed institutional public defenders.”

“An urgent threat to public safety”

Other states that rely heavily on court-appointed attorneys have faced similar shortages.

In Maine, a lack of public defenders contributed to the release of a man with a history of violence in June 2024. Three days later, he killed one person and engaged in an hourslong standoff with police before dying himself. The case drew national attention and prompted efforts to create more permanent public defender offices.

Oregon has faced its own severe backlog, with roughly 4,000 defendants statewide awaiting legal representation. In Multnomah County alone, nearly 300 cases, including felonies, were dismissed because no public defender was available. Former District Attorney Mike Schmidt called the shortage “an urgent threat to public safety.” Oregon is now moving toward a hybrid model, hiring additional public defenders to handle at least 30% of indigent cases by 2035.

Massachusetts is home to a large number of law schools and lawyers. That abundant supply has, ironically, contributed to the low pay.

“Massachusetts is getting an incredible bargain out of bar advocates,” says Robert Kilmartin, a longtime federal attorney who became a bar advocate after retiring to Cape Cod. “But it’s at the expense of the Sixth Amendment.”

He worries that the low pay makes it nearly impossible to recruit and retain talented lawyers. “If we can’t attract good lawyers, the system collapses,” he says. “And that collapse isn’t just about us – it’s about the thousands of people left unrepresented in court.”

with the largest raise in two decades – a $20 increase spread over two years – and pledged to hire 320 new public defenders. By the end of August, the state had hired 22 new staff attorneys.

Massachusetts acted faster than many states, notes Aditi Goel of the Sixth Amendment Center, a nonprofit tracking public defense nationally. “Other states don’t have as sophisticated a structure,” she says. “When they face a crisis, they may not even be aware that there is one.”

However, despite the increase in pay, many bar advocates have not resumed taking new cases. The Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers¬Ý called the raise insufficient to resolve what it described as a ‚Äúconstitutional crisis.‚Äù

The stakes extend far beyond clogged court dockets. A loss of confidence in the system may be as damaging as the backlog itself, says Aliza Hochman Bloom, assistant professor of law and an expert on criminal procedure at Northeastern University.

“Most individuals within our carceral system already have a waning sense of the integrity of the system itself,” says Ms. Bloom. “Lack of access to counsel further erodes that trust.”