From life in prison to out on parole: One group easing the transition

Loading...

| San Francisco

During the time he was serving 18 years to life for second-degree murder, Joe Calderon would reflect on an incident from his childhood in which he and his cash-strapped parents were living in the family station wagon. They pulled into a Kentucky Fried Chicken for dinner, but there was only enough money to feed “little Joey.”

While the attendant was distracted, little Joey’s father burst in, jumped over the counter, threw 20 or so pieces of chicken into a bucket, and ran out. Mr. Calderon remembers being overjoyed that there was enough chicken for everyone. In his young mind, it was the beginning of “the little linkages between survival and crime.”

Those linkages would eventually lead to gang involvement and the fatal shooting of a security guard during a botched robbery attempt. His gun was perpetually hot and ready. “I was a knucklehead,” Mr. Calderon says of his turbulent past.

Why We Wrote This

“Lifers” who get a chance at parole have singular needs. In California, one pioneering program to support them enlists ex-offenders. “They’re going to hold you accountable in ways that nobody else can,” says the relative of a lifer.

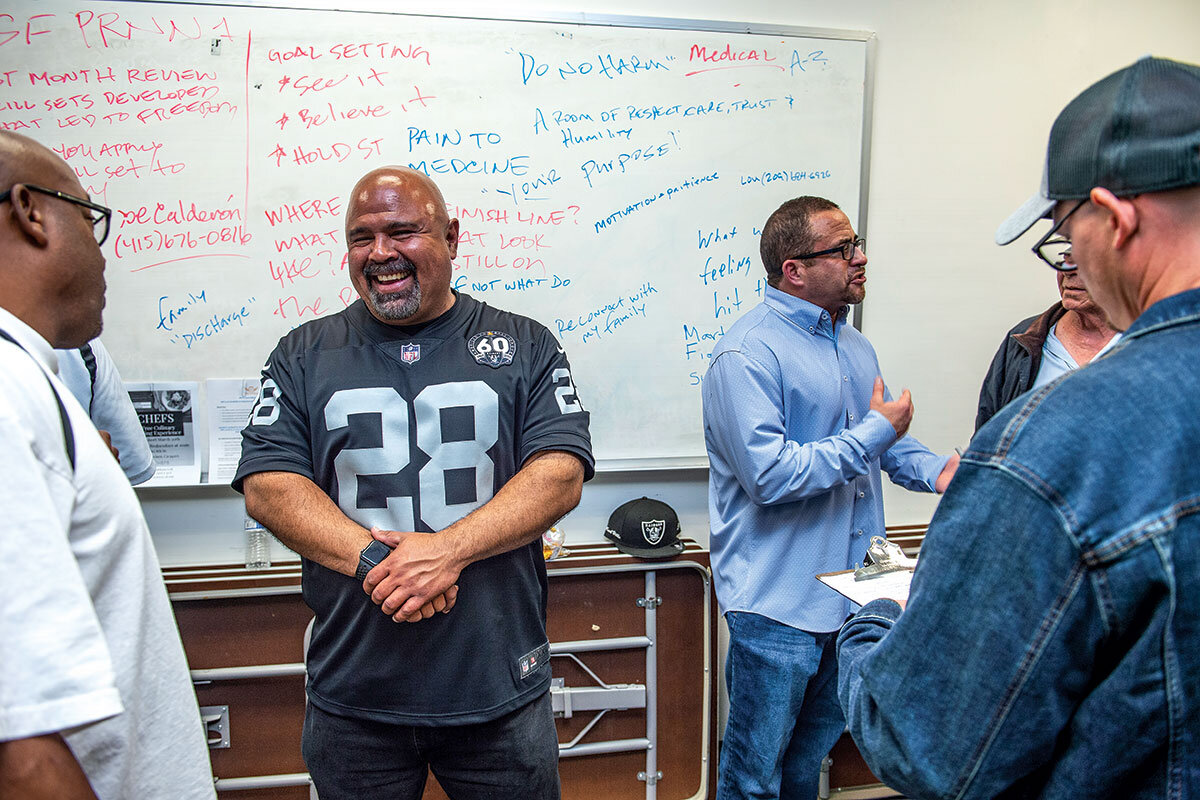

On a recent morning, he was scribbling the words SELF-LOVE on a whiteboard in front of a boisterous roomful of former knucklehead criminals like himself. A disciplined type with the biceps to prove it, Mr. Calderon now serves as a peer mentor and Yoda of sorts to some 50 men, and a smattering of women, who meet on the second Tuesday of every month at the parole office of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation in San Francisco.

They’ve gathered for a pioneering program designed to support the singular needs of “lifers” who are returning to “the free world,” as they tend to call it, after decades in prison. Nearly all did time for murder. At one point, they figured out there were 1,462.5 years of prison time in the room.

“I was addicted to the hustle,” says Mr. Calderon, who is also a senior community health worker for a network of health clinics for the formerly incarcerated.

The parole group, which has a rotating cast of characters and a new theme each month, is officially called the Peer Reentry Navigation Network (PRNN). The program was launched five years ago in response to the unprecedented number of lifers being released in California, which has the largest number of inmates with life sentences in the world, just over 34,000.

For years, the chances of a lifer being released were slim to none, which remains the case in many states. In California, that began to change in 2008 with key legal decisions that shifted the basis for parole from the heinousness of the original crime to the question of whether an inmate, if released, would pose a serious risk to public safety. Since 2010, more than 6,000 people with life terms have been granted parole.

“It’s not prison bravado or social pleasantries,” Mr. Calderon says of the group. “It’s real.”

For the newly released, heady with freedom in the makeshift classroom, the tripwires of daily life lie in wait. Most entered prison young and headstrong and have come home as middle-aged Rip van Winkles with bad backs and a host of more serious chronic conditions. Forty-five to 60 years old on average, with many looking far older due to decades of confinement, they have never used a smartphone, Googled an old flame, memorized a PIN, or swiped a touch screen. They are starting from scratch at a point where others their age are watching their 401(k)s.

They have made it through the excruciatingly complex gauntlet of parole, a protracted process that demands intense introspection and accountability for one’s crimes; years of participation in groups dedicated to substance use disorder, domestic violence, and other issues; and a detailed reentry plan.

But the universe outside the gate is more daunting still. When Mr. Calderon writes SELF-LOVE/HEALING RELATIONSHIPS WITH SELF on the whiteboard, the responses of the group are telling:

I left a lot of guys in prison I love. I did 41 years. I can’t beat myself up for the fact that they’re still there.

They took me away from females, and in my mind, I have a lot to make up for. That’s undue pressure that can distort your thinking. I need to stay in the slow lane. Settling for someone is not self-love.

Safe space for frank talk

The group’s premise is that those who have successfully navigated life on the outside are best suited to light the way for others. Although the atmosphere varies month to month, the meetings always provide safe space for frank talk. It’s a freewheeling blend of mutual aid, self-help, 12-steppish recovery, tips for defusing triggers, and a network for building social capital, with job leads and resources frequently coming from alumni. It also includes advice for the lovelorn – as in, “I’m having a relationship with more than one woman.” Mr. Calderon’s response: “Be careful about cheating. That’s a sign you’re going south fast.”

It’s a place for learning from each other’s mistakes. “I’d suggest that if you have a substance issue, stay on it,” Englebert “Bert” Perlas tells the group one morning before taking off for work as a glazer in an orange construction sweatshirt and caulk-splattered pants. “I thought my 20 years of sobriety in prison meant I got this thing beat. But coming off a hard day’s work ... the beers in the fridge ... the glistening condensation. It was ... ‘that’d be good.’”

The cascading effect of his brief relapse with alcohol led to what he says is a domestic violence charge, two restraining orders, and a parole violation for which he is still in legal limbo. He is prohibited from seeing his 3-year-old daughter, which visibly grieves him. “Sobriety has to be No. 1,” he cautions. “I’m living proof of that.”

Shadd Maruna, a criminologist at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland, considers experts-by-experience like Mr. Calderon to be “wounded healers.” Mr. Calderon thinks of his work as “living amends.” “Helping is my medicine,” he explains. “It keeps me humble.”

The meetings were piloted here in “felon-friendly” San Francisco. Along with Los Angeles, the city has a plethora of services mandated by the parole board and California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, including job skills training and six-month transitional housing, where blood-alcohol and urine tests, metal detectors, and tight curfews are the norm. Los Angeles County and the San Francisco Bay Area are home to what experts say is the densest concentration of released lifers in the country.

The concept for the group was loosely based on a Canadian correction services program, since closed, that trained former lifers to mentor incarcerated people and parolees. “Lifers build communities with each other in prison, so the group is a way of extending the runway,” says Elizabeth Kita, a clinical social worker who helped develop the program for the parole office in San Francisco. “Most have been in groups for decades. So having people they can talk to, check in with, and give and get ‘pull ups’ instead of ‘push downs’ is important.”

The consideration of releasing long-term offenders began in earnest in California under Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown, who morphed from a tough-on-crime governor in his first term to a believer in rehabilitation and second chances. Mr. Brown created a special parole process for inmates who committed their crimes as juveniles and were charged as adults. (Mr. Perlas was one.) In 2011, the governor appointed Jennifer Shaffer as executive officer of the state’s Board of Parole Hearings. At that time, “it was not uncommon for lifers to not know of anyone who had been granted parole and released,” Ms. Shaffer says. “Now every lifer knows someone who went home.”

Unlike younger parolees, whose social networks often remain relatively stable, lifers have been removed from society for decades. Nationwide, the population of prisoners sentenced to life increased by nearly five times between 1989 and 2016, according to the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit criminal justice organization. The escalation, in which African Americans were almost seven times more likely to be incarcerated for violent crimes than white people, was the result of harsh laws that increased mandatory minimums for criminal sentences.

The PRNN, which has since expanded to 28 locales statewide, was designed to exploit the protective factors that studies show help released prisoners succeed. Chief among them is a sense of agency and being around people who model “pro-social” behavior, in criminology-speak.

Researchers have found that people tend to age out of criminality and that lifers who have been released after many years in prison have a low risk of recidivism. “There is a misconception that those who have committed murder will re-offend in violent crime,” says Tarika Daftary-Kapur, an associate professor at Montclair State University in New Jersey, who found a 1.14% recidivism rate in a recent study of juveniles in Philadelphia who were sentenced to life without the possibility of parole and later released.

Ms. Shaffer reminds parolees that they have a responsibility to succeed not just for themselves and the safety of the community but also for those remaining “behind the wall.”

“They’re not higher risk, despite their crimes,” she says. “But they are high stakes.”

For Mr. Calderon, who was 23 at the time of his crime, “heavy changes” occurred within him while holding his daughter Jessica (now 26) during prison visits. “My dad chased skirts and was never around,” he says. “I had told myself if I ever had kids, I’d do better.”

But his status as a respected professional does not always inoculate him from the aftershocks of incarceration, such as getting hypervigilant in public places because of years of watching his back in prison. When he catches himself in vulnerable situations, he picks up the phone and calls a lifer brother.

“Get over ‘I’m going to do it myself,’” Mr. Calderon tells the assembled throng at meetings. “The most important people you have are the people in this room.”

SIX-MONTH GOALS FOR 2020:

Get a driver’s license.

Get my tattoos removed.

Stay drug and alcohol free.

Get a job.

Learn how to tie a tie.

Meet the grandkids I’ve never met.

To not go back where I came from.

Many lifers who have been released say prison saved their lives. They grew up in households where unspeakable trauma and abuse occurred, which can sometimes result in a razor-thin line between victim and perpetrator. “It’s a twisted irony that in prison, one of the most trauma-inducing places ever created, people are expected to find a safe space to heal from trauma and understand their own fears, motivations, and decisions,” says Keith Wattley, a lawyer and founding executive director of the Oakland-based nonprofit UnCommon Law, who specializes in lifers seeking parole. “Personal transformation isn’t something that’s imposed on people; it’s something they demand and create for themselves.”

Wanting to be “Scarface”

Louie Hammonds Sr., who co-facilitates the parole group with Mr. Calderon, was once “Lou-Dog,” a major gang leader on the fearsome south side of Stockton, California. “I wanted to be ‘Scarface,’” Mr. Hammonds muses, referring to the vicious drug lord played by Al Pacino in the 1983 movie. “People would say, ‘Do you see how he died?’ And I’d say, ‘Do you see how he lived?’”

When Mr. Hammonds was 12, a drunken driver crashed into the family car, hurling him and his 10-year-old sister through the windshield. Both children were hospitalized, and his sister died shortly thereafter. He says his mother, a retired military officer, had a nervous breakdown and his father, a bartender, spiraled into addiction. Young Mr. Hammonds found himself overcome with guilt and shame, convinced that “my sister sacrificed her life for mine because she went through the window first.”

He had already been sniffing gas and paint in alleyways. His emotionally distant father had a close friend who was a big shot in a gang. Mr. Hammonds was impressed by a scene he witnessed in an alley where a 5-foot-2-inch gang leader, with a reputation for violence, had scores of bigger and brawnier young men held rapt in his orbit. If he could wield that kind of power, Mr. Hammonds reasoned, perhaps his father would love him.

He transformed himself into the Scarface of Stockton, presiding over a savage milieu in which “keeping up with the Joneses” meant killing them. After shooting an unsuspecting man at a bar seven times with a 9 mm handgun, he was incarcerated and, deemed a security threat, ultimately sent to Pelican Bay State Prison, the notorious supermax that houses the state’s most violent offenders.

“In our belief system,” Mr. Hammonds says of being sent there, “that was a graduation, a bar mitzvah, a coming of age.”

Ruthless and dangerous, Mr. Hammonds was assigned to a high-security housing unit, where gang leaders steeped him in the manifold tactics of war against corrections officers – making knives from clipboards by sharpening the metal fasteners on concrete floors, for instance.

One day, Mr. Hammonds cooked up an excuse to visit the medical unit, his hands shackled to a waist chain. Two officers brandishing batons escorted him. Along the way, Mr. Hammonds realized that one of his sneakers had come untied. He noticed another corrections officer heading their way and waited for the guards accompanying him to press him against the wall so their colleague could pass by. Instead, he recalls, the approaching guard “leans down on one leg and ties my shoe, doing it in a bunny knot like my grandmother used to. Then he walks away. He humbled me. He didn’t break the glass ceiling of my insanity all the way, but he cracked it. He had humanity in him, and when he touched my spirit, he gave me some of that humanity.”

Thus began Mr. Hammonds’ slow journey from the precipice to the multidimensional person he now is – someone who was always inside him, he insists, but whom he never learned to protect. The process involved extensive debriefings with gang investigators and multiple prison transfers.

Today, Mr. Hammonds supervises the citywide COVID-19 response for Urban Alchemy, a California nonprofit that monitors the safety and habitability of public spaces and is committed to hiring former lifers, many from PRNN.

He is keenly aware of the things that trip people up – especially relationships. “You’re dealing with issues and emotions out here that are unfamiliar to you,” Mr. Hammonds observes. “There’s no way to adequately develop in a men’s correctional setting. You’re not being open. You’re afraid to cry. It stunts your development. So you’re behind the curve coming out.”

Reestablishing meaningful connections with family members is by far the thorniest task lifers face. “So many of them are at different stages than you are,” says Mr. Calderon, who has several cousins who are still involved in “the life.” “Many are unhealthy for my reentry [back into society], as much as it hurts my heart.”

A rude awakening

The divide between outside reality and hopes and fantasies nurtured behind bars can be devastating. “I believed I was going to reunite with my son, only to find out it was not something he wanted,” says Aminah Elster. “If you dreamt all those years, how do you deal with that rejection?” Her young son lived with her parents while she was incarcerated, though she had an iffy relationship with both, especially her mother, before she was imprisoned.

Ms. Elster earned a community college degree in prison, where she did 14 years for being an accessory to a murder. Released in 2017, she recently graduated from the University of California, Berkeley in legal studies and coordinates an ambassador program for formerly incarcerated students. She has just started a nonprofit to address gender imbalances in reentry programs like PRNN, which can be rife with testosterone.

She regularly greets newly released lifers at the prison gates. “We have to show people how to love us,” she observed at a PRNN meeting. “Because other folks mimic that.”

Available for lifers 24/7

The idea that a murderer might be capable of undergoing the kind of social, emotional, and moral metamorphosis necessary to be worthy of love is a difficult concept for many people to grasp. Among the skeptics was Martin Figueroa, a guiding force behind the PRNN program who now oversees lifers out on parole for the state department of corrections in Alameda County. “I thought ... this is going to be scary,” he says of his first lifer parolee – a guy named Calderon.

Mr. Figueroa, who has a master’s degree in counseling psychology and won a Jefferson Award for Public Service, grew up in a violent neighborhood similar to his charges, a place where “everyone expects you to be nothing.” He encourages his parolees to call him 24/7.

He also fields calls from distraught family members. In the foreground of every release are the survivors whose lives have been shattered by the acts of violence marking the lifers’ pasts. Mr. Figueroa puts it this way: “How do we balance recovery and public safety? We want to maximize their success reintegrating with society, but we want to honor the victims as well. If a lifer is committed to giving back to the community, it can give the victim’s families solace that the person has turned their life around.”

While he has his parolees’ best interests at heart, public safety comes first. If a released lifer is returned to custody, “a little part of me dies,” he says. “Because I had so much hope for them.”

One cautionary tale

When Clinton Thomas was released from San Quentin in 2014, he quickly became the charismatic and articulate public face of the returning citizen. He was the golden boy who met with the mayor, the ex-lifer who crushed it on public television.

Mr. Thomas had grown up in East Oakland, where his mother, a nurse, developed a heroin addiction. He lived alone with her as the household descended into poverty. Upon her death, his behavior was so out of control that a family member put him on a bus to Texas to live with his father, whom he barely knew. By the time Mr. Thomas returned to Oakland, the streets were overrun with crack cocaine. His best friend, who had dropped out of school after eighth grade, had become “hood rich” with designer clothes and a fancy car. Mr. Thomas wanted in.

He was 17 years old when he persuaded two friends to help steal a suitcase full of cash sitting in a “drug house” down the block. At the time, the neighborhood was a narcotics bazaar and Mr. Thomas had become an excellent salesman. Though his goal that day was mercenary, one of his friends wanted to extract revenge from a girl at the house who he thought had informed the cops about an earlier killing. When the friend pulled out his gun, Mr. Thomas was already bolting out the door and heard the screams as he ran to the nearby railroad tracks – the “little getaway” from his youth where he and other boys would throw rocks and watch pennies get flattened as trains sped by.

Mr. Thomas was arrested in 1991, tried as an adult, and convicted of first-degree murder. He entered the adult system at age 18. He got out 26 years later after a new state law required meaningful parole opportunities for juveniles who were tried as adults and convicted. He was 44.

Mr. Thomas was a stellar parolee. But during Year 3, several problematical developments started to undermine his newfound – and, it would turn out, shaky – stability. Working as a welder, a skill he learned in prison, Mr. Thomas was injured by a falling piece of steel and started taking opioid painkillers so he could continue working. Then he moved on to cocaine to stave off dope sickness.

The illness and death of his older sister – who had been his legal guardian and a sort of second mother – nudged him further downward. Mr. Thomas withdrew from the community of lifers as well as his family. He started violating parole, walking away from his residential substance abuse treatment program, and flying to Miami with one of many girlfriends, in defiance of his 50-mile travel limit. While there, he accidentally pocket-called Mr. Figueroa. He couldn’t bring himself to lie about where he was.

He says he almost dropped the phone. “It broke my heart,” Mr. Figueroa recalls.

Mr. Thomas spent two years back in San Quentin before being released earlier this year. Forsaking his peers after his first parole was a major contributor to his unraveling, says his brother Gary Welch. “I believe you have to stay with the community of lifers out there,” he says. “They’re going to tell you the truth, push you to a higher plateau. They’re going to hold you accountable in ways that nobody else can.”

Mr. Thomas revisited his old haunts in East Oakland recently. He retraced his steps from the faded peach-stucco house where he committed his life crime to the railroad tracks down the block from the childhood home where he and Mr. Welch raised homing pigeons on the roof as youngsters.

He had not set foot on this ground for 32 years and the grief caught him unaware. “I remember the victimization and the hurt,” he says, dabbing his eyes. “My mother taught me better than that.”

He is grateful that he is now in a different place, living in transitional housing with a good job and a fiancée he has known since their teens, and regularly attending the monthly meetings. Mr. Thomas says he has learned the hard way “to never stop communicating with your support system.”

“I didn’t use the tools in my toolbox,” he acknowledged in a phone call from San Quentin last year. “Stress came and I thought I had it licked.”

Back at the PRNN meeting, Mr. Calderon stands at the whiteboard, where he’s written another topic, and responses to it.

FIRST TIME YOU HIT THE GATE:

My family picked me up. They told me “we wear seat belts out here.” I’m still in awe.

My uncle came. I thought, “let’s get out of here before they change their minds.”

We went to Denny’s. It felt weird to have people treating me nice. I felt I was undeserving.

I was wearing a sweatshirt. People weren’t paying any attention to me. It was my dysfunctional thinking that everyone knew where I was coming from.

On the whiteboard, Mr. Calderon writes, “What is your finish line?” “Are you still on the path and if not, what do you do to get there?”

Afterward, Mr. Hammonds suggests to the group: “Let your character be your currency.”

They are all saving up.