Fort Hood trial: Odd legal dance as both sides appear to seek death penalty

Loading...

| Atlanta

What started as a horrific attack, in which Maj. Nidal Hasan is accused of an act of ultimate treachery by shooting scores of unsuspecting fellow soldiers at Fort Hood in 2009, has by turns and twists emerged as a bizarre legal drama playing out in an ultra-fortified compound in Killeen, Texas.

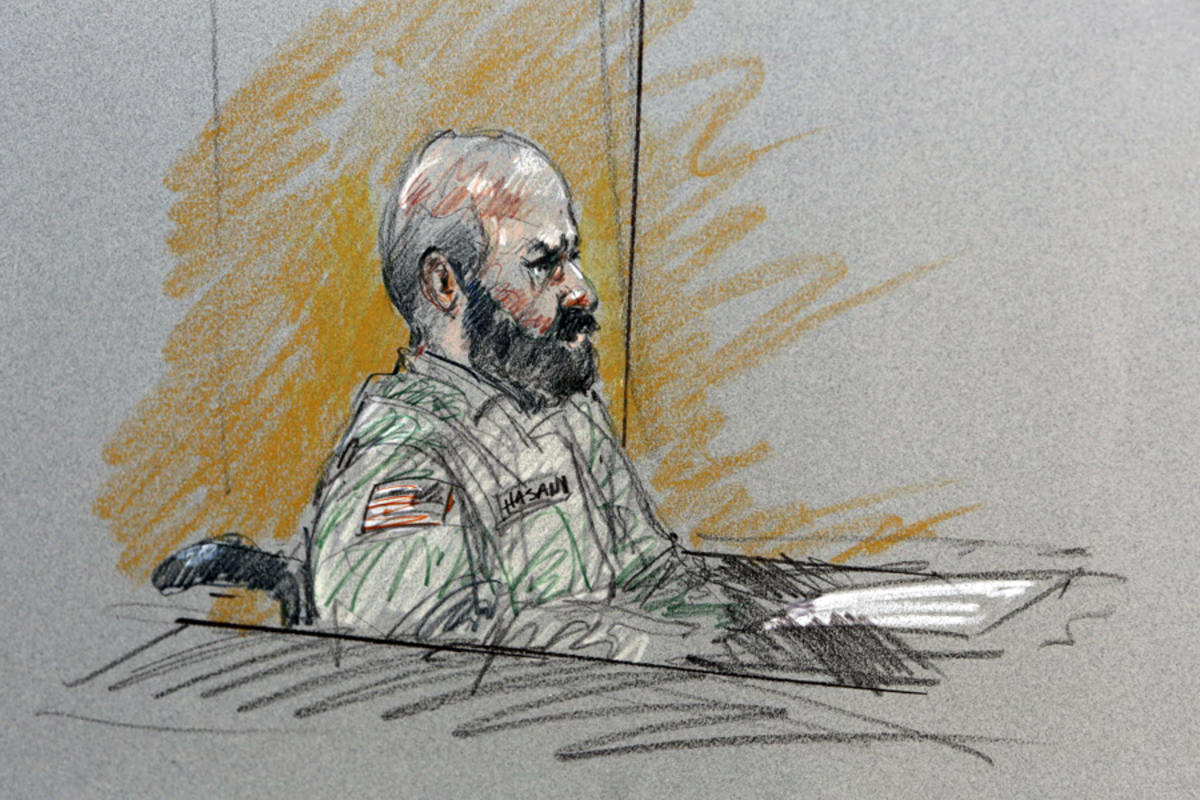

The trial of Major Hasan, a radicalized psychiatrist who has elected to represent himself at trial and who admitted on Tuesday that “I am the shooter,” saw its first major delay on Wednesday after Hasan’s court-appointed standby defense lawyers raised new objections about his defense strategy.

Hasan’s lawyers suggestion that Hasan is ultimately not interested in defending himself added more complexity to a unique situation in which the Army’s main intent is to give Hasan a capital verdict that is iron-clad against appeals by coaxing him to defend himself.

Some Americans feared a circus atmosphere at the trial in which Hasan is given a jihadi soapbox while subjecting victims to cross-examination by their tormentor. While the trial is likely to take more turns, Hasan declined to cross-examine one of his victims on Tuesday, and has so far kept comments restrained and to a minimum.

But given his lawyers’ contention on Wednesday, the trial has become, if not a show trial, a strange sort of legal dance. The court wants to give Hasan every opportunity to avoid the death penalty in order to keep the expected death sentence from being overturned on appeal. (Eleven of the last 16 capital courts martial sentences have been overturned.) Hasan’s goal, meanwhile, may be martyrdom, to die at the hands of Uncle Sam, putting the Army into the position of having to convince Hasan to fight the death penalty in order to execute him.

“This is really one of the most bizarre proceedings in the annals of legal history,” says Aitan Goelman, a government prosecutor in the Oklahoma City bombing trial of Timothy McVeigh. “It sounds like [what we’re seeing] is a long guilty plea. As opposed to a trial where there’s actually material facts … and what his mindset was” in dispute, “it sounds to me like he doesn’t really disagree with the government’s allegations – he just thinks he was justified. The outcomes of those kinds of trials aren’t really in doubt.”

The evidence is seemingly ironclad. Hasan, yelling “God is great!” in Arabic, is accused of firing more than 200 rounds from a semi-automatic rifle into throngs of troops at the Soldier Readiness Center at Fort Hood on Nov. 5, 2009, killing 13 and injuring scores more, many seriously.

The case has come to the court martial courtroom on Fort Hood after many delays and twists. A judge had to be dismissed because of a bureaucratic and philosophical argument about whether Hasan should be able to wear the beard he grew in custody to court, or shave per Army regulations. The beard won out.

Then as the trial was about to start in June, Hasan fired his appointed lawyers, and told the judge, Col. Tara Osborn, that he would use a “defense of others” argument in his own defense – that he was trying to protect the lives of Taliban soldiers and leaders by attacking deploying soldiers. The judge denied that motion.

Hasan also pleaded with the judge to let him admit his guilt, but she said no, largely because military prosecutors are pushing for the death penalty, which can’t be applied in plea deals.

The bulk of the rulings so far have been focused on giving Hasan every benefit of the doubt in order to serve military justice.

“Capital trials are rare, and they’re even more rare in the military jurisdiction, and so you have that fact added to the unusual events in this case, such as the accused wants to represent himself,” says Maj. Gen. (Ret.) John Altenburg, the former appointing authority for military commissions for Guantánamo detainees. “This puts pressure on the judge and prosecutors to exercise great care to ensure he gets a fair trial.”

Hasan’s lawyers filed a motion Wednesday saying that they could no longer in good conscience serve as his back-up counsel, because they believe Hasan is actively vying for the death penalty. That motion led to an early end to a day of testimony as the judge considers her next move.

Hasan, however, argued that the attorneys were wrong. "That [assertion is] a twist of the facts," Hasan said.

The backdrop to the case is also intriguing, with many of the victims bitterly complaining that they’ve been denied combat benefits after the Pentagon deemed the shooting an act of workplace violence instead of an act of war.

The official reasoning for not calling it an act of war is it would jeopardize the case because “defense counsel will argue that Major Hasan cannot receive a fair trial because a branch of government has indirectly declared that Major Hasan is a terrorist – that he is criminally culpable,” according to a Pentagon memo.

Also, victims’ lawyers have filed a lawsuit claiming that the Army failed to pick up on seemingly obvious signs of a problem with Hasan, including an incident in which Army colleagues booed him for defending the use of suicide bombers in a speech. The FBI also knew that Hasan had been in contact with Anwar al-Awlaki, the US-born radical cleric who was killed by a drone strike in Yemen, but bought his explanation that it was simple research.

The victims’ suit contends that the Army “knew or should have known that Hasan was abusing his patients, who were American soldiers returning from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan, by calling them ‘war criminals’ in the course of psychiatric treatment sessions, and promising criminal prosecution against them because these soldiers had killed Taliban and other terrorists in Afghanistan and Iraq.”

As far as the facts of the massacre, however, military prosecutors are charging that Hasan saw himself as a mujahid, a holy warrior who switched sides and killed his comrades, for which he has earned the death penalty.

"He came to believe he had a jihad duty to kill as many soldiers as possible," said Col. Steve Henricks, the lead prosecutor.