Echoes of Northern Ireland peace plan in Trump’s ideas for Gaza

Loading...

| London

After decades of violence, in a conflict long assumed to be beyond hope of resolution, there is “a truly historic opportunity for a new beginning.”

That was the animating spirit behind the plan President Donald Trump launched this week to end two years of devastating war in Gaza and bring peace to the Middle East.

But the words come from the opening page of another plan, aimed at resolving another, equally intractable conflict: the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which ended three decades of sectarian killing in Northern Ireland.

Why We Wrote This

The outlook for peace in Gaza and the wider Middle East is not bright. But prospects for success were not encouraging in Northern Ireland 30 years ago, either. And that is not the only common factor between the two situations.

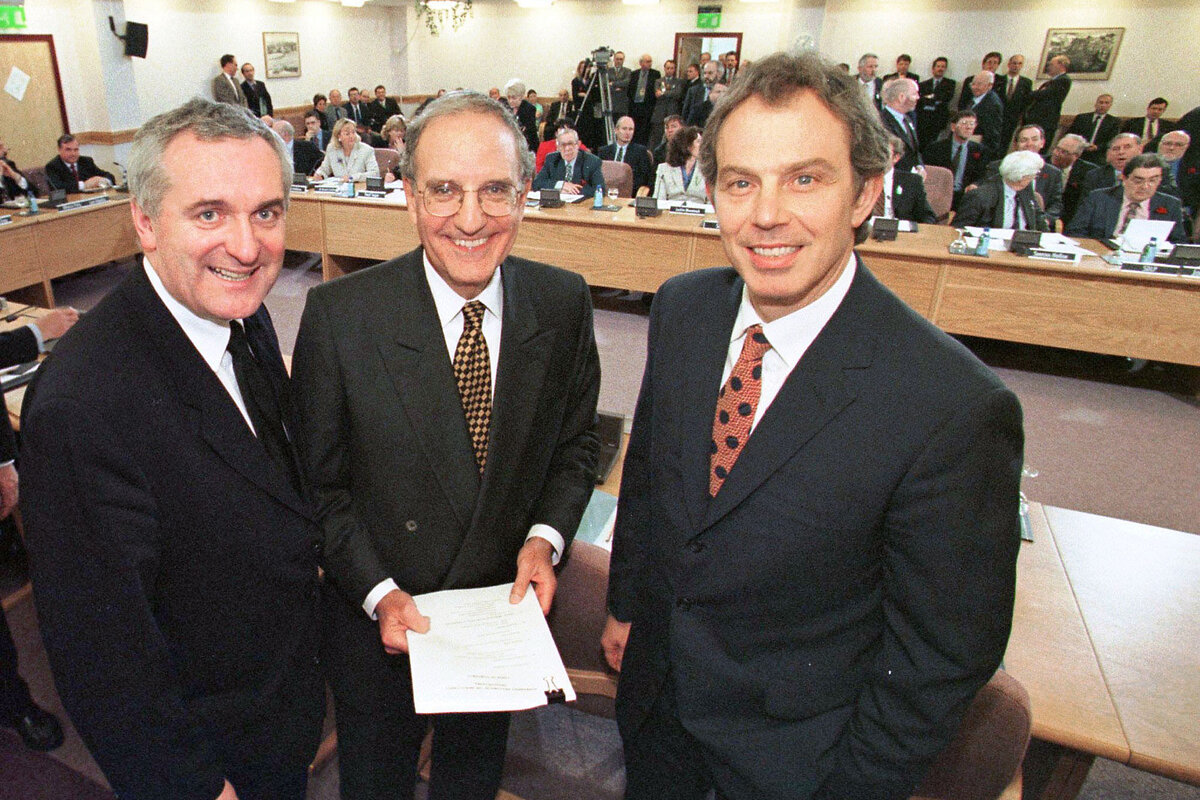

And while Mr. Trump is unquestionably the driving force behind the Gaza initiative, his plan bears remarkable similarities to the peace process in Northern Ireland that former British Prime Minister Tony Blair helped steer to success.

Mr. Blair did get a brief mention at the White House launch of the Gaza plan. Mr. Trump said this “very good man” would be a member of his international oversight body guiding an intended transition to a post-Hamas government.

But far more significant are the strong echoes of the Good Friday agreement in the 20-point Gaza peace plan: its design and strategy, its core assumptions, and a number of its key details.

Mr. Trump’s blueprint rests on the hope that what worked in Northern Ireland will work in Gaza, and on one assumption above all: that Israelis and Palestinians are ready to accept that continued violence won’t get either of them what they want.

The extent to which the Northern Ireland parallel holds true will determine which of three possible Gaza scenarios plays out in the days, weeks, and months ahead.

The plan could hit an early dead end. Hamas or Israel could balk, leading to a renewed Israeli military assault on Gaza with Mr. Trump’s nod of approval.

Or the first stage of the plan might meet with success, an important achievement in itself.

That would involve a ceasefire, an exchange of Israeli hostages held by Hamas and Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails, and – crucially – a respite from months of catastrophic violence and humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

And then there is the ultimate hope: a triumph on the scale of the Good Friday accord, ushering in a stable, secure, economically revived Gaza that opens a path to wider Israeli-Palestinian peace.

Mr. Blair well knows the difficulties and frustrations of Middle East peacemaking.

As British prime minister, he worked with Israeli, Palestinian, and Arab leaders to try to nudge the region toward peace. He continued those efforts after leaving Downing Street, when he became the representative of what is known as the Quartet, a diplomatic group consisting of America, Russia, the European Union, and the United Nations.

Now, however, Mr. Blair is banking on his long-held conviction that the lessons of Northern Ireland could break the Israeli-Palestinian logjam and deliver wider Middle East peace.

Key lessons have been woven into the Gaza plan.

It is a stage-by-stage blueprint, focusing initially on ending the violence and leaving the thorniest political questions for later.

Using the Good Friday mechanism, it aims to build trust steadily through provisions for prisoner releases, amnesties, and the placing of Hamas’ weapons “verifiably beyond use,” as the Northern Ireland agreement put it.

And it all hinges on strong, sustained involvement by outside leaders who the warring parties will listen to and trust.

In Northern Ireland, the fundamental issue was the future political identity of the majority Protestant region – established as part of the United Kingdom when mainly Catholic Ireland became an independent country.

Northern Ireland’s Protestants were unshakably committed to remaining part of the United Kingdom. Many Catholics wanted to join a single, united Ireland. In the 1960s, the argument turned violent, with paramilitaries on both sides engaging in a campaign of punishment beatings, killings, and bombings as thousands of British troops struggled to keep order.

The Good Friday Agreement set out a vision for devolved government including both Protestants and Catholics.

The core question of whether Northern Ireland would remain part of Britain or join the Republic of Ireland was left open, to be resolved at some future stage by popular referendum.

Key to its success was the commitment of the governments of Britain, Ireland, and the United States. Then-President Bill Clinton was deeply invested. George Mitchell, the retired U.S. senator named as his Northern Ireland envoy, played an indispensable role as independent chairman of the negotiations.

Both Mr. Blair and President Trump are evidently hoping key elements of the Northern Ireland approach will prove replicable in Gaza.

But they will also be aware of a key difference.

In Northern Ireland, by the time peace talks got underway, all major political and military actors had concluded that it was in their interest to find a way to end the violence.

And civilians on both sides, despite a deep and abiding mistrust between the Catholic and Protestant communities, had also had enough. Proof of this came in the Northern Ireland referendum required for the agreement to take effect. Eight in 10 people voted. A resounding 71% of them voted yes.

That’s something far from evident in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Still, it had taken Northern Ireland 700 days of intense negotiations to reach such a point. When they began, and at numerous points along the way, success had seemed a distant prospect.

It is that hard-won transformation, most of all, that the authors of Trump's plan hope to replicate.