A pivotal grade at a pivotal time: What is it like being an eighth grader today?

Loading...

| Oak Park, Ill.

Inside a small staff room at Percy Julian Middle School in Oak Park, Illinois, Lyla Czerniawski and three friends are making a video for incoming sixth graders about middle school life.

As they bat around suggestions, one student interrupts with a question that is arguably the elephant in the room.

ãWait ã did we all like middle school?ã she asks.

Why We Wrote This

Todayãs eighth graders are shaped by pandemic learning and issues with student engagement that followed. What do they have to say about their education ã and how it looks moving forward?

The eighth graders erupt in laughter.

ãYes and no,ã Lyla replies.

How students fare in middle school directly correlates to their high school experience and college and career readiness. Academics tend to agree that eighth grade is particularly formative. Studentsã thoughts about themselves and their place in the world begin to weigh more heavily on the cusp of high school. Amid sagging test scores and chronic absenteeism in the United States, a growing cadre of academic experts point to the importance of student engagement at this age.

ãWe see engagement drop dramatically in the middle grades and then continue to fall off in high school,ã says Ashley N. Leonard, founding director of the To&Through Middle Grades Network at the University of Chicago. ãThis disengagement happens because students are like, ãI donãt see the relevance to my life anymore.ãã

So how do these young teens ã who were third graders when the pandemic began and kindergartners when President Donald Trump first took office ã perceive school and their life beyond childhood?

The answer to that question offers a glimpse into the psyche of this generation of digital natives who eye the world ã and the American education system ã with a dose of skepticism.

College aspirations and realities

Percy Julian Middle School sits on a block surrounded by tidy older homes and stately brick apartment buildings in Oak Park.

This Chicago-adjacent village skews more affluent and educated than other suburbs. Nearly three-quarters of adults age 25 or older living here possess at least a bachelorãs degree. Demographically, itãs slightly more diverse, with a population that is 63% white, 20% Black, 9% Hispanic, and 6% Asian.

ãI used to say that my job was to get them ready to be accepted into the finest colleges and universities that this country has to offer,ã says Ashley Kannan, a longtime history teacher at the school. ãI do remember that word for word.ã

Itãs not a given anymore. Even some of the strongest students groan at the concept of college. Thatãs new here. ãI just havenãt had that [before], especially in a community like Oak Park,ã he says.

For some students, such as Caden Ruess, itãs complicated. He doesnãt miss a beat when asked about his post-high school aspirations. The eighth grader says if he were to ãteleport to senior yearã and select a field of study, he would triple major in political science, pre-law, and anthropology.

That means college for sure, right?

ãNo,ã he says, drawing out the vowel sound. ãItãs so expensive.ã

The eighth graders surveyed by the Monitor expressed mixed enthusiasm about the prospect of college ã and to be fair, that could change within the next four years. A few gave an automatic yes. Others appeared to think postsecondary education was likely in some form, but not a forgone conclusion.

Antonio Alesia, a soft-spoken eighth grader, fiddles with Canva, an online design tool, in his spare time. If he pursues a graphic design career, he says, college might be on the horizon. For now, he is more interested in snagging a summer job ã perhaps at a relativeãs yoga studio ã to earn spending money.

His mother, TaTyana Bonds, isnãt pushing him in either direction. Ms. Bonds, who also attended Percy Julian Middle School, tried a bit of college and cosmetology school before ultimately becoming a professional mixologist. She followed her passion and wants Antonio to do the same.

ãIãm not going to make him go to college or apply for colleges,ã she says, adding that his happiness and well-being are more important. ãI tell him every day when I drop him off at school, ãI love you. Make healthy choices. Have a great day.ãã

Total postsecondary enrollment climbed 4.5% in fall 2024, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The spike brought undergraduate enrollment to 1% shy of 2019 levels, assuaging some concerns about tepid interest in higher education. But the number of high school graduates is expected to peak this year and decline for the next decade and a half.

In his classroom, Mr. Kannan has retooled his approach to the college conversation. Now, he views it as ãmore of an individual, case-by-case situation. Whereas before, I think I looked at it as a blanket statement.ã

Getting students to be fans of school

Part of the solution may lie in keeping kids motivated ã and interested ã in school.

Rebecca Winthrop, co-author of ãThe Disengaged Teen,ã says student engagement should be viewed as the ice cream of a sundae, not just the cherry on top.

ãWe should put it at the center and then layer other things on top, rather than put other things in the middle and try to add engagement at the end,ã says Ms. Winthrop, who is also director of the Center for Universal Education at The Brookings Institution.

By all accounts, Lyla, the Oak Park eighth grader, is a model student. She pays attention, completes her work, and exudes quiet leadership traits. She balances academics with dance class several times a week after school. But she says coming here each day rarely excites her.

ãMy mom tells me, ãWhy donãt you like school? You have friends. You have good grades,ãã she says. ãBut I donãt know. Iãm just not a huge fan.ã

Tempting as it might be to brush this off as adolescent indifference, Lyla can articulate what does motivate her. In Mr. Kannanãs class, she enjoyed designing T-shirts featuring Reconstruction-era themes. In science, she liked debating ethical questions surrounding controversial experiments.

What could make school better? ãListening to how students say they need to be taught or how they need to learn,ã she says.

Caden, who enjoys strategy games like Catan and hopes to join the high school debate team, has thought about this, too. He envisions a more individualized approach that gives students freedom to move at their own pace. Indeed, some schools and teachers are already heading in that direction.

ãI used to really like most schoolwork, but recently, it has become very same-y and very boring,ã he says. Too often, attending school ãjust feels like itãs there to be there.ã

Their observations donãt surprise Lylaãs father, Mike Czerniawski, who works as a school improvement coordinator for a regional office of education. He says his daughter and her peers seem more comfortable questioning the status quo.

ãMy generation and my parentsã generation were just sort of accepting of like, ãOK, this is schoolã ... without any thought that it even could be different,ã he says.

Mr. Kannan, the teacher, agrees. He for the Chicago Tribune entitled, ãAre the kids all right? They experience school very differently than we did.ã

Before his first class even begins one morning in early March, a girl tears up over a social media post. He quietly talks to her and the other student involved. At lunchtime, his room fills up with students escaping the cafeteria. This is their safe space, away from stressful social scenes or what they perceive as rigid rules. Later in the afternoon, he chats with his eighth graders one-on-one as they complete assignments about the Holocaust. Post-pandemic, he says, direct instruction doesnãt work. Students zone out. But he finds they open up, delivering insightful commentary, when he meets with them individually.

A veteran educator of 28 years, Mr. Kannan worries the education system as a whole isnãt designed for their needs.

ãNuance and complexity is being put to the side for simplicity,ã he says.

His case in point: textbooks and related assignments the school district was evaluating for possible purchase. Students quickly snubbed them.

ãTo be completely honest, I donãt remember much of anything from the textbooks because they were copy-paste,ã eighth grader Adela Portincaso says.

Instead, Adela lights up talking about ãScythe,ã the dystopian novel byô Neal Shustermanô sheãs reading in her English class, and a related opinion research paper.

Her teacher, Laurel Niedospial, let students choose a dystopian novel to read and an accompanying project. Students tend to be more engaged that way, she says, and ãsee the world through a thematic lens.ã

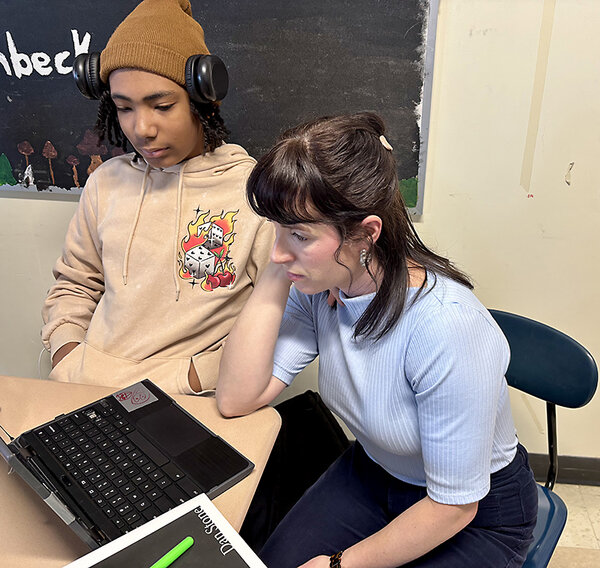

In March, Antonio sits in her classroom, his headphones slightly askew as his fingers whiz across the keyboard. Heãs writing a dystopian short story. Naturally reserved, he is not short on words when describing the plot and his enthusiasm for the project.

ãItãs just something Iãve been interested in,ã he says.

Wanted: ãgood teenage yearsã

Saying goodbye to middle school comes with dual emotions for eighth grader Alaina Paskar.

ãIãm extremely nervous for high school,ã she says at first.

Minutes later: ãIãm just ready to get out now.ã

Her friend dynamics changed this year and so did school leadership for the third time. With a new principal comes new rules.

ãHonestly, that might be something that you might want to write down,ã Alaina says, before rattling off policies about lunch schedules, cellphones, and backpacks.

The topic surfaced multiple times during interviews with students, underscoring their desire for consistency in a school experience that hasnãt always delivered that. COVID-19-era policies brought upheaval at a time when they were transitioning from learning to read to reading to learn. These eighth graders spent the end of third grade and much of fourth grade sidelined to remote instruction.

Though usually quick to shrug off the pandemic, the students acknowledge its lingering effects. Eighth grader Naomi Reed, for instance, says she never learned division. Her parents taught her that math concept instead.

ãIt was just different,ã Naomi says, recalling desks spread wide apart at the end of fourth grade.

Looking ahead, Naomi and her peers say they are eager, even if apprehensive, for a fresh start. New school. New friends. More autonomy and more interesting classes.

ãI feel like I can make a new image of myself,ã she says. Where Naomi does that is yet to be determined. Sheãs on the waitlist for her top choice, a magnet school in neighboring Chicago.

Alaina, for her part, admits she spends time preoccupied about the future. How will it feel to leave her parentsã house one day? What career does she want to pursue? She hasnãt decided but knows she wants ãgood teenage years.ã

ãThe anticipation for going into middle school is way worse than actually doing it,ã she says. ãAnd I hope itãs the same way for high school.ã

That sentiment is what brings Lyla and her three friends to the principalãs office in mid-April. They finished their vlog ã a video blog ã for incoming sixth graders. Itãs filled with advice and slices of their daily life, from boarding buses to using lockers.

Now, they have a request: They want to visit elementary schools and present it to fifth graders.

Ms. Leonard, of the To&Through Middle Grades Network, says this type of student-led initiative needs to be embraced more often.

ãWhen you give young people the opportunity, they will rise to the occasion,ã she says. ãToo often we donãt give them the opportunity because, as adults, weãre too afraid to let things go, and we feel like we need to control it or have a say in it in ways that arenãt always helpful.ã

After the studentsã sales pitch, the principal agrees to their request. The girls leave giddy with excitement.

Itãs their gift to the next generation.