Designing life: How college courses in coping are booming

Loading...

| Northampton, Mass.

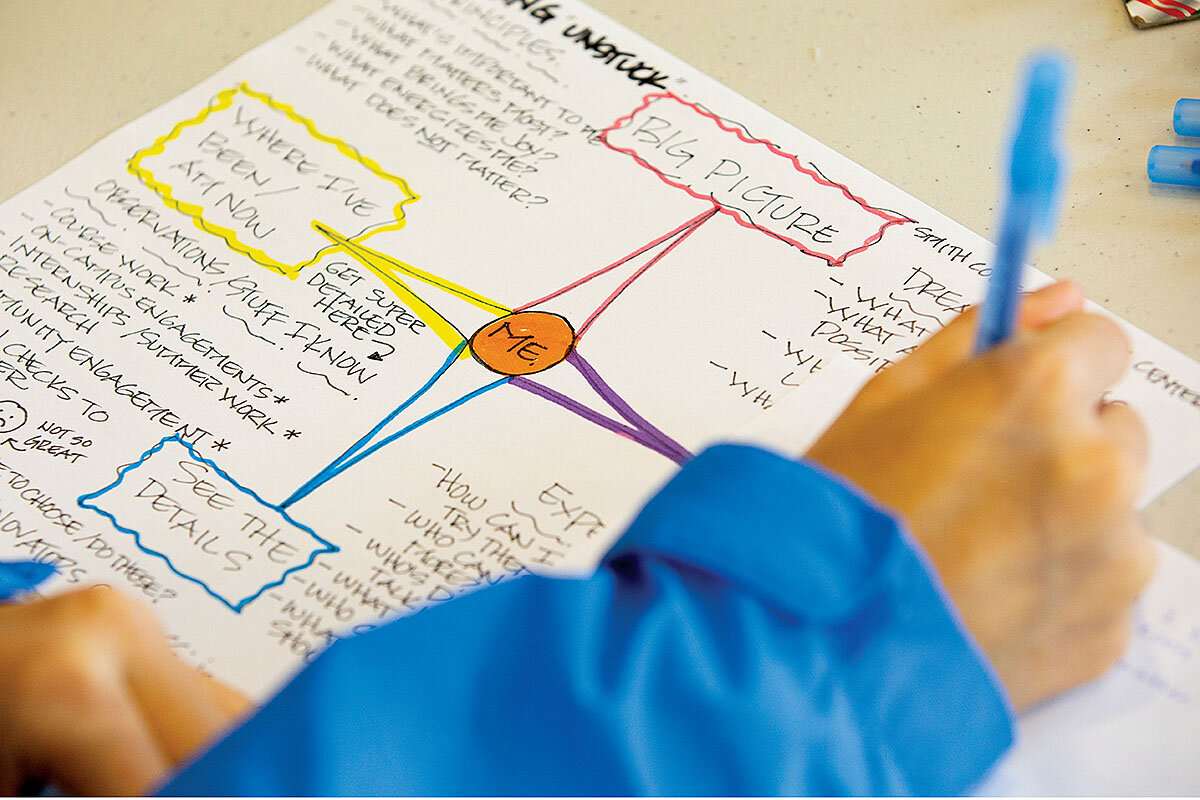

On a recent weekday in a classroom at Smith College, a dozen or so undergraduates hunch over circular tables, scribbling intently. Their teacher strolls around the room, past sticker-covered laptops and water bottles, looking down at the laser-focused students.

“I want you to get really, really detailed,” she says.�� ��

They write.

Why We Wrote This

Higher education of an earlier era focused on contemplation of character, values, and how to live a good life. But today’s shift to achievement as the goal has students seeking more meaning.

“OK,” she says a few moments later, and the students sigh. Not enough time. “Now I want you to check in with your partner.”

There is some awkward shifting of chairs. And then, quietly, they begin to read off their worksheets.

“I just – I don’t know how to fit in all my goals in my weekly schedule.”

“Where do I want to live? What do I want to do?”

“I feel pulled in multiple directions at once.”

“Family is really important to me. Wherever I end up, I want to be near them. But that’s limiting, you know?”

Stacie Hagenbaugh, director of Smith’s Lazarus Center for Career Development, moves quietly around the room. This is the fifth time she has taught the Getting Unstuck When You Don’t Know What’s Next workshop, a new course that has been gaining attention across campus. So she is not surprised by what she’s hearing.��

“Students often get really overwhelmed by all the possibilities,” she says. “There’s so much – the clutter in their heads gets in the way.”

The goal of Getting Unstuck is to help students focus, and to fill what many are increasingly pointing out as a gaping hole in modern college education – a lack of attention to those big life questions about what matters, how to be happy, and what to do next. It is one of a number of similar initiatives that Ms. Hagenbaugh has helped launch on campus over the past three years.��

She is far from alone in her work. Over the past few years, there has been a groundswell of courses nationwide that focus on how to help a notoriously stressed-out generation of college students learn how to approach life better. These initiatives are at big state schools and Ivy League universities; at art schools and business schools; through massive open online courses, or MOOCs; and over podcasts.

And students have responded in huge numbers. At Yale University, when psychology professor Laurie Santos offered a new course last year called Psychology and the Good Life, some 1,200 students – nearly a quarter of the undergraduate population – enrolled. It is now considered the most popular course in the school’s history. At Stanford University, the Designing Your Life class taught by Silicon Valley veterans Dave Evans and Bill Burnett became so popular that it evolved into the Stanford Life Design Lab, which runs undergraduate and graduate courses and other programs across campus. The lab's Life Design Studio has trained teams from 140 universities around the world, according to Gabrielle Santa-Donato, who runs the studio training program. Mr. Evans and Mr. Burnett’s 2016 book, “Designing Your Life,” stemming from the course quickly became a New York Times bestseller. And when Emiliana Simon-Thomas, the science director of the University of California, Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, recently released her Science of Happiness course on the edX platform, more than 600,000 people enrolled.

“I think we’re at a tipping point with universities,” says Julia Lang, assistant director for career education at Tulane University’s Taylor Center for Social Innovation and Design Thinking. “How are universities remaining relevant? How are we creating students who are prepared to become change agents in society?”��

To help answer these questions, Ms. Lang began a life design course for a few students in 2016. Since then it has grown exponentially across the university; today it has more than two dozen sections taking place everywhere from the career center to the athletics department.

“College students are filled with so much information, but nobody has taken the time to ask them who they are and what do they care about and what sort of life do you want to build,” Ms. Lang says. “There is a huge need.”

Behind Gen Z student stress

The intensity of that need is, perhaps, found in some of the statistics about the mental health of this generation of students. A 2018 report from the American College Health Association found that more than 60% of college students said they had experienced “overwhelming anxiety” within the past year; the rates of depression among young people have doubled in the past decade. Talk to university administrators, and many say that student mental health is among their most pressing concerns.

There are many explanations for this apparent rising stress level among undergraduates. Some administrators suggest that a generation of helicopter parents has left children unable to function independently.��

“Students are coming to college with parents who have been so closely attending to every move,” says Julie Lythcott-Haims, a former dean of students at Stanford who wrote the book “How to Raise an Adult.” “When they’re outside the house, they are with parents. When they’re inside the house, they are with parents. They are never alone. I think we are going to learn years hence that the constant observation and tethering will really weaken them.”

But others say that this generation of college students – often called Gen Z, or sometimes iGen – is facing its own unique set of challenges thanks to an economic, political, and technological world fundamentally different from even a decade ago, adding to young people’s apprehension.

According to Pew Research Center, faith in government in the United States is at a historic low, with only 17% of the American public saying they trust lawmakers in Washington. Only 21% of college students say they have confidence in the news media, according to a 2018 report by the Panetta Institute for Public Policy. And although social media use has skyrocketed, with Pew research finding that 95% of teens have access to smartphones and 45% say they are online “almost constantly,” nearly 50% say they feel overwhelmed by the drama contained in what they read on their devices. ��

��

All of this comes on top of unprecedented student loan debt – a cause of worry “often” or “somewhat often” for 65% of college students, according to the Panetta Institute report. Add a rapidly changing job landscape, and it’s no surprise college students have anxiety, many administrators say.

“We’re definitely seeing a shift with students who are feeling more overwhelmed and anxious about what they’re going to be doing next,” says Ms. Hagenbaugh. “It is a rapidly changing professional environment. The students who are first years will likely graduate and walk into a job that didn’t exist when they started. It feels overwhelming.”

“Wicked problems”

Many of the life courses that have sprung up on campuses are deliberately geared toward addressing this sort of unknown future. They are built around “design thinking,” a problem-solving approach popular in the tech world that has moved into the mainstream in the past few years.

“It’s a process that’s all about wrestling with ambiguity,” says Kathy Davies, managing director of Stanford’s Life Design Lab. “It’s all about what we call ‘wicked problems’ – problems that don’t have a solution, that can’t be solved with money. And that’s life, right?”

Design thinking – and life design, when design thinking is applied to oneself – focuses on brainstorming (think flow journals and list-making), innovating, and prototyping, which is tech jargon for experimenting. There’s an emphasis on trying things out and having “small failures” – early, quick lessons that help steer one to a better path.

“If you sum it all up, it’s about getting curious,” says Ms. Davies. “What do I care about enough to invest time and energy in? It’s about trying things. About reflecting, doing it again, and being able to connect the dots.”��

For many students, getting away from a culture of executing tasks is emotionally groundbreaking. Researchers at California State University, Dominguez Hills found that participants in designing-life programs had less career anxiety, increased hope and resilience, and a better ability to create options for themselves than before they started.

“There is a real cognitive shift around exploration, risk-taking, and the ability to control one’s destiny in the face of real change,” Ms. Davies says.

This was certainly true for Julia Sagaser. As she started her senior year at Smith, she felt overwhelmed.

She had already switched majors once during college – from pre-med to film and media studies – but she still felt she was in the wrong field. A grueling combination of internships, schoolwork, and extracurricular projects had left her exhausted. She was scheduled to graduate in December, but she had no idea what she was going to do then, or even what she would do over the upcoming summer.

“I was really trying to reassess,” she says. “But I wasn’t sure what to do.”

Tasks toward self-knowledge

She emailed the career center and asked about the Getting Unstuck workshop, which she had been hearing about around school. Soon, Ms. Sagaser was filling out a worksheet, in the shape of a compass, titled “The Big Picture.” She listed her dreams, what was important to her, and what she had learned from past work and academic experiences. At the same time, she began designing experiments that could “test out” future life paths, whether that meant interviewing professionals already in a particular field or shadowing someone at a job. She started a Pinterest board with images she found inspiring for her life. And she began to envision an internship project that fit in with her broader life goals – whether that meant working in nature or being close to her parents in Maine.��

Slowly, she says, the anxiety level began to lower. She found an organization doing the sort of work she found interesting – the Wells Reserve at Laudholm in York County, Maine – and convinced people there to allow her to intern for the summer. There, she began a research and film project.��

While Ms. Sagaser still doesn’t know what she is planning to do after graduation, she says she isn’t as worried about it. She keeps an oversized copy of her Getting Unstuck compass pinned to her dorm room wall.

“I came to learn that a path doesn’t have to already be carved out for you, and it doesn’t have to be a linear one, with concrete steps,” she says. “Once I discovered that those cookie-cutter paths are few and far between, and when they do exist they’re really illusions, that felt better. Because everyone is in the same place. It’s not like anyone is the weirdo who doesn’t have it all figured out.”

Not knowing is OK

Mr. Evans began the Designing Your Life course in part to help more people have this revelation. He says the seeds for his work began in the early 1970s when he was an undergraduate at Stanford and went to the career center for help.

“They said, ‘What do you want to do?’” he recalls. “And I said, ‘Right. What do I want to do?’ They said, ‘No, that’s not how this works.’” Now, Mr. Evans says, we might not expect students to know exactly what they want to do, but “we keep asking, ‘What’s your passion? What’s your passion?’”

Which, he and others say, is a ridiculous question for college students.

“Passion comes after trying something out in the real world,” says Ms. Lang of Tulane University. “How is a student supposed to know what they’re passionate about when most of their life they’ve been in school?”

In 2000, Mr. Evans began teaching a course at the University of California, Berkeley called Finding Your Vocation (aka Is Your Calling Calling?) with the goal of offering an alternative way for students to start exploring what they might want to do in their adult lives. What he intended to be a one-semester seminar evolved into years of teaching, with more and more students eager to take the class. In 2007, he and Mr. Burnett decided to try out a version of the course for design students at Stanford – an initiative that has expanded into the sweeping life design movement.

“[Poet] Mary Oliver said it – ‘what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?’” Mr. Evans says. “That question matters to people. The zeitgeist of wisdom addressing that question is not working for people. What we are suggesting is working for people.”

And that, he says, is because his course, and the many iterations of it across the country, is about designing a life, not picking a career.

“It’s not just designing your job,” he says. “It’s love, play, work, and health. ... A well-lived and joyful life is the goal we are trying to help people attain.”

Long ago, a focus on living well

Some skeptics might suggest that universities do not need to be in the business of fostering joy. But historians point out that a few generations past, higher learning was all about the meaning of life.

“The missions of schools in this country when they were first founded was about how to live well,” says Emily Esfahani Smith, author of “The Power of Meaning: Finding Fulfillment in a World Obsessed With Happiness.” With overtly religious missions, she says, schools were intentionally focused on “how to live a good life.”

And to help students do that, universities based their curricula on the great books – those foundational texts of Western civilization in which philosophers contemplated big life questions. Professors unabashedly taught “duty” and “character” without fear of charges of paternalism or cultural colonialism. (It’s worth pointing out that both students and professors were primarily white men from relatively privileged, homogeneous backgrounds, some university administrators say.) But as Ms. Smith writes in her book, secular humanism soon pushed religious mission out of the academy. Political correctness and specialization further reduced universitywide conversations about morals and values, she says.

The result is a higher education system that focuses on “achievement for the sake of achievement,” Ms. Smith says.

Others agree.

“Academia, as a sector of society, really does rest on individualistic, competitive cultural values,” says Ms. Simon-Thomas of Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center. “It’s the scarcity orientation – there’s only this much money, there are only this many seats, only so many people who can be successful. When we find ourselves trying to navigate various decisions where scarcity is the overarching framework, people veer toward self-interest.”

Yet a lot of research shows that following self-interest – whether it’s buying a new car, working for a promotion, or holing up in a dorm room to ace a test – tends to make people feel lousy.

Exploring ideas like this was a focus of Ms. Santos’ class at Yale. In the course, she spoke regularly about the difference between what people think will make them happy and what actually leads to true happiness. “So many of our intuitions are wrong,” she says.�� ��

Ms. Santos recently launched a podcast, “The Happiness Lab,” that delves into these misconceptions. Episodes focus on the “unhappy millionaire,” for example, exploring how, after a certain point, money does not improve happiness.

Time and space to think

But at the same time, there is research showing which actions do improve happiness, Ms. Santos says. Taking time for social connection is one. So is practicing gratitude.��

One reason her class was so popular, she suspects, is that she delved into these concrete practices, giving her students assignments – in other words, time – to try them out. “It wasn’t supposed to be another psychology class,” she says.

Indeed, the time and space to practice good life habits, Ms. Lang says, are key parts of the courses she and others teach at Tulane. Many students, she says, realize that reflection and brainstorming are important, but with schedules that have been overprescribed since they were in elementary school, they’ve never had the opportunity to focus on these skills, or, really, themselves. ��

“They are at this crucial point in their development,” Ms. Lang says. “They still have a lot on their shoulders, from other people’s expectation. Every year has been another tick on the belt. From kindergarten you go to first grade. From high school you go to college. They’ve never had the platform to take a step off that ladder and look at it.”

In her classes she asks students to do various reflection exercises, such as thinking about the three most powerful adults who affected their lives as children, and then exploring how those people approached work and home. She asks students to come up with three potential life pathways, and talk to fellow classmates about how they might test those ideas.

“We give students the opportunity to pause,” she says.

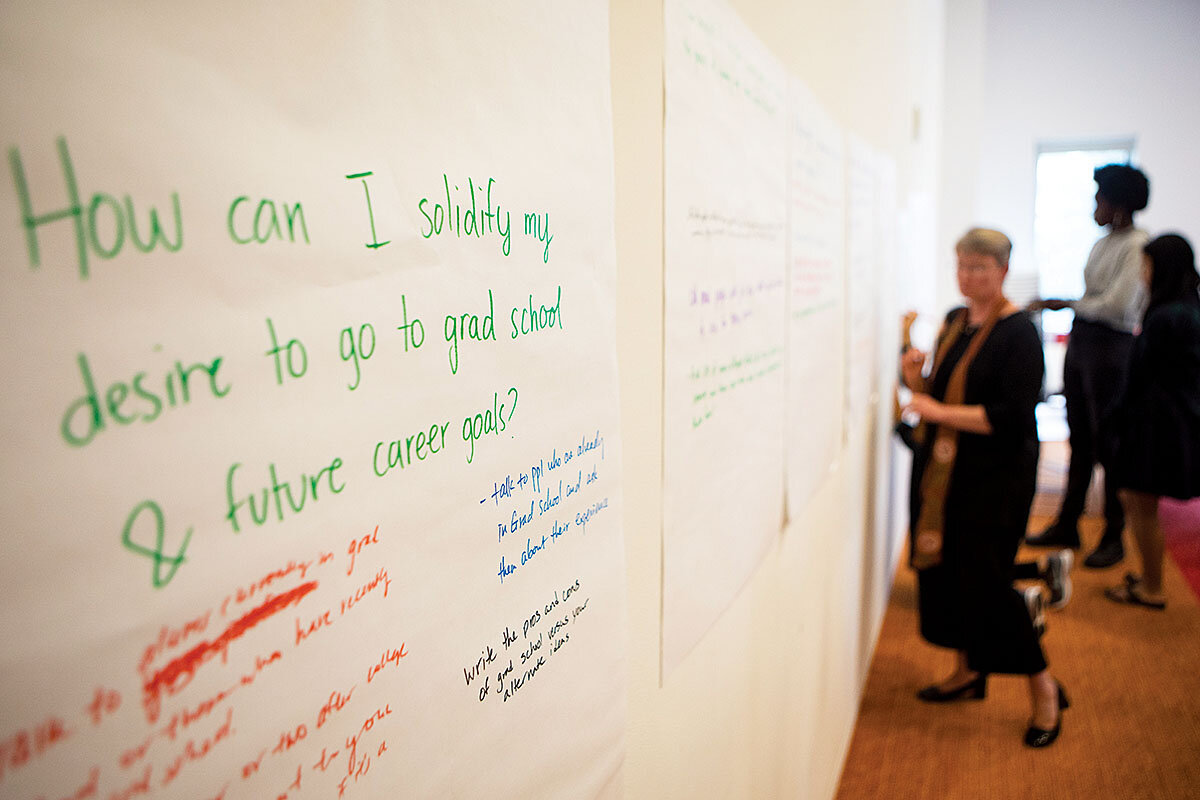

As the Getting Unstuck workshop nears its end, Ms. Hagenbaugh asks her students to change all of their problem statements into “How might I” questions.��

“What’s a piece of the puzzle that you can work towards?” she asks.

Then she instructs them to write those queries on large sheets of paper she has left in the middle of their tables.

Peri Navarro, a senior, grabs a green marker. “How might I motivate more to focus on what matters?” she writes.

Ms. Hagenbaugh gives the students some time, and then tells them to attach their sheets to the walls of the classroom. She encourages them to walk around and read other people’s questions, and to fill in suggestions.

Ms. Navarro walks slowly. She came to the Getting Unstuck workshop with some big questions, about where she wants to live, what she wants to do, whether she should go to graduate school, and how to incorporate environmentalism into her next steps.

When the workshop ends, she still seems deep in thought. “It’s great to have these questions,” she says. “I need to think more about them. This is a start.”