The Eat Pray Love effect: Prom vs. Machu Picchu

Loading...

| San Diego

Pulling up stakes and leaving it all behind from the first-grader chafing at the bounds of school and parents with work stress, but is not all Eat, Pray, Love, as the gauzy movie may have suggested. Traveling together 24 hours a day, seven days a week can present for even the closest of families.

Tara Russell, a San Francisco-based certified life and career coach specializing in long-term travel, tells her clients that extended travel is not the solution to family dysfunction: “Whatever is dogging you here will dog you 10 times more on the road.”

For example: A missed prom might trump Machu Picchu in one family member’s mind, or a flat tire in a windstorm might spark a family spat.

Rainer Jenss, who left an executive position at National Geographic, says spending so much time with his wife magnified some of their issues. “We have very different parenting styles, but it never affected us that much. When we were traveling, though, it was harder to work out.” But, he adds, “You develop patience on a much deeper level.”

, corporate communications consultant who took his family on the road for a year in 2008, says his kids had a tough time when their friends from home would communicate with them by e-mail or on��������Ǵǰ�. “They could see what their classmates were doing and it hurt. My daughter was supposed to be starting high school and she was very connected to her friends.”

When she missed her first homecoming dance, having boyfriends, or a new “Twilight” movie, he explains, “she would be depressed.... Never mind we’d been to Machu Picchu that day, when there was a party she had missed.”

In April, during a week when the Podlesny family was traveling in their mobile home through Texas, and the wind was blowing at 70 miles per hour, they got on each other’s nerves, says Danielle. In fact they had to reschedule their interview for this story to change a blown tire, the third one that week. The windy conditions made it impossible for the family to get out and explore. “It was frustrating, and we were feeling cooped up,” she says.

For Dee Andrews, whose family left Boulder, Colo. to travel for a year, the toughest time came about six weeks into the trip, when they were setting up to live for a time in Spain. “It became stressful and tedious. You’re trying to deal with the phone company, get Internet service, buy groceries, only you’re doing it in a foreign language and culture. I was living the same life only in a different place,” she says.

Dee recalls a night in Barcelona when her youngest daughter Grace, age 6 at the time, was under the bed crying because she missed her dog and wanted to go home. In hindsight, she believes those challenges were good: “We pushed ourselves to do new things. I think it made us stronger, happier, and healthier.”

And that sentiment – that these trips were well worth navigating the difficulties – is nearly universal. Rainer tells how, after his chidren toured Bhutan, a Buddhist enclave in the Himalayas, his youngest son began building little shrines in the hotel rooms where the family was staying. “Visiting Bhutan was the least kid-friendly thing we did, and yet my younger son was really drawn into it – the customs, the culture, and the aesthetic. It was such a surprise to us,” he says.

The “most amazing” experience for Craig was a family feast in Cambodia. Their driver invited them to dinner at his home, near Phnom Penh.

“He lived in a shantytown, and his house was brick with dirt floors. We walked in, and his wife had prepared this amazing dinner for us. A dozen neighbors were there. We ate on a slatted bed that doubled as their dining table. It was the most amazing experience for all of us, to see this kind of generosity,” he recounts.

Craig says he got to know the kids in a way that stationary, suburban life in Silver Spring, Md. didn’t allow: “We talked a lot about our family history and about ourselves. In our regular lives, most conversations were about logistics or instruction, from us as adults to our children. When we were traveling, we had the space for a different kind of conversation, about big ideas. It was like conversations you might have in a college dorm room.”

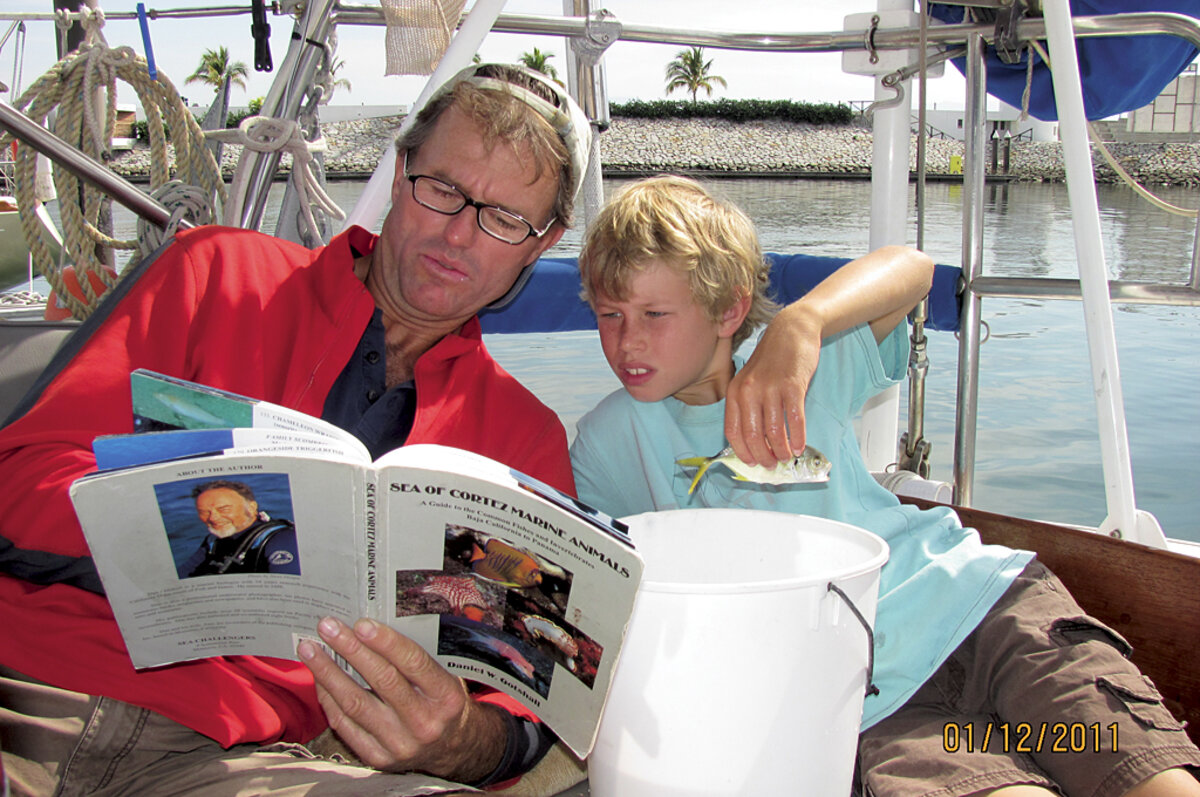

, who left suburban San Diego to establish a home in Baja California from which they spent time at sea on a sailboat, found that being together so much, especially in a place where everyone wasn’t just like them, helped her children “come out of themselves” and be comfortable around different kinds of people. They are self-assured but less self-centered, she says, than typical kids their age. Ann’s son, Henry Wyatt, 9, told her the months spent on the boat were the best of his life.

“Being able to fish every day, gather seashells, go to really secluded beaches on the Sea of Cortez for weeks on end was heaven for Henry,” says Ann. “The real adjustment for him will be if and when we emerge back in the States.”

��

��

��