Whose ŌĆśNutcrackerŌĆÖ? Rethinking a Christmas staple.

Loading...

For more than 50 years ŌĆ£The NutcrackerŌĆØ has been synonymous with Christmas. Along with holiday cheer, the ballet generates anywhere from 20% to 50% of most ballet companiesŌĆÖ revenue. While many live performances of ŌĆ£The NutcrackerŌĆØ have been canceled this year due to the pandemic, the classic ballet remains a beloved holiday tradition and inspires legions of children to take up ballet.┬Ā

But in recent years, many in the dance community have been asking how to reconcile this ballet that they love with the stereotypes that it has helped to perpetuate. They wonder if it is possible to transform ŌĆ£The NutcrackerŌĆØ to remove its racial stereotypes and aristocratic origins while holding onto its traditional charms. Three dance companies have answered this question with a resounding ŌĆ£yes,ŌĆØ keeping the balletŌĆÖs essence while widening its appeal to include diverse audiences. WeŌĆÖll get to them shortly. But first, a little history.┬Ā

Russian origins

Why We Wrote This

Many ballet fans find comfort ushering in the holiday season with ŌĆ£The Nutcracker.ŌĆØ But in recent years, choreographers have been looking for ways to make that traditional classic feel more inclusive.

ŌĆ£The Nutcracker,ŌĆØ with music by Pyotr Tchaikovsky and choreography by Marius Petipa, premiered at the Imperial Mariinsky Ballet in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1892. It was not the huge hit that it is today. Critics assailed the production for its prominent use of children. Instead of dancers portraying royal courtiers, a nod to the imperial family and visiting dignitaries, as was customary at the time, the ballet follows the plot of a childrenŌĆÖs story, E.T.A. HoffmannŌĆÖs ŌĆ£The Nutcracker and the Mouse King.ŌĆØ In the story, a girl named Clara (or sometimes Marie) visits an enchanted world of delicious treats accompanied by a Nutcracker prince. The ballet underwent many revisions before it eventually found lasting success in Russia.

An American beginning

In the United States, George Balanchine, co-founder of New York City Ballet, created his American-friendly version, based upon his memories of dancing at Mariinsky Theatre as a child. The result was a smash hit, though he continued to tinker with it throughout his life.┬Ā

BalanchineŌĆÖs initial version premiered on Feb. 2, 1954, at a crucial point in New York City BalletŌĆÖs history. Though the company had its passionate supporters, Kay Mazzo, a former principal ballerina and the current chairman of faculty for the companyŌĆÖs School of American Ballet, has recalled times when there were more people onstage than there were in the audience. Balanchine changed all of that by featuring children from the school, which drew in family members.

What proved a liability in the original Russian production became a formula for success in America. With the Dec. 25, 1958, broadcast of ŌĆ£The NutcrackerŌĆØ on CBS, the ballet became forever associated with Christmas. It also helped establish a winning tradition across the nation that brings families together and introduces many young people to ballet.

Time for an update

Not all audiences have been delighted with every aspect of ŌĆ£The Nutcracker.ŌĆØ In Act 2, dancers portraying sweets from different cultures (chocolate from Spain, coffee from Arabia, tea from China) appear onstage. The traditional choreography and costumes ŌĆō particularly in the Chinese section ŌĆō reinforced stereotypes that are demeaning and offensive. For example, the Chinese section featured dancers in yellowface, performing inauthentic, if not mocking, gestures.┬Ā

In 2017, Phil Chan, a scholar, educator, and former dancer, convinced New York City Ballet to drop the offending antics and costume pieces. For another production, at the Pacific Northwest Ballet in Seattle, he consulted with Peter Boal, the artistic director, to rethink the Chinese section.

ŌĆ£The original Balanchine ŌĆśNutcrackerŌĆÖ version is essentially an emasculated Chinese coolie,ŌĆØ Mr. Chan says. ŌĆ£Instead of that, Peter chose a cricket, which in Chinese culture is a symbol of spring. And just as Balanchine dancers are the most musical of ballet dancers, crickets are also the most musical of insects.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Most importantly for Mr. Chan, it shows Chinese people that ŌĆ£the choreographer actually took something from my culture that was respectful, as opposed to an outdated caricature from 150 years ago.ŌĆØ The current costume for the cricket is still being workshopped, but for now, families can watch Pacific Northwest BalletŌĆÖs production of BalanchineŌĆÖs ŌĆ£The NutcrackerŌĆØ ŌĆō without the offensive costumes and gestures ŌĆō on its website: www.pnb.org/nutcracker/.

Bold adaptation

Honest representation was also on Sam PottŌĆÖs mind when he created ŌĆ£Jersey City Nutcracker.ŌĆØ The founder and director of Nimbus Dance in Jersey City, New Jersey, says, ŌĆ£It was important for European immigrants to have shows like ŌĆśNutcrackerŌĆÖ that connected them back to their European traditions. But sometimes that was wedded to white supremacy.ŌĆØ ThatŌĆÖs why, instead of showcasing the traditional aristocratic family of the story, this version features children from different economic backgrounds traveling to ŌĆ£the safer and kinder Jersey City of their dreams,ŌĆØ he says.┬Ā

This approach to the ballet was inspired by the work of childrenŌĆÖs author Ezra Jack Keats to signal that ŌĆ£kids have a sense of wonder regardless of their economic circumstances,ŌĆØ Mr. Potts says. ŌĆ£Jersey City Nutcracker: The MovieŌĆØ is available on demand through its website:┬Āwww.nimbusdance.org.┬Ā

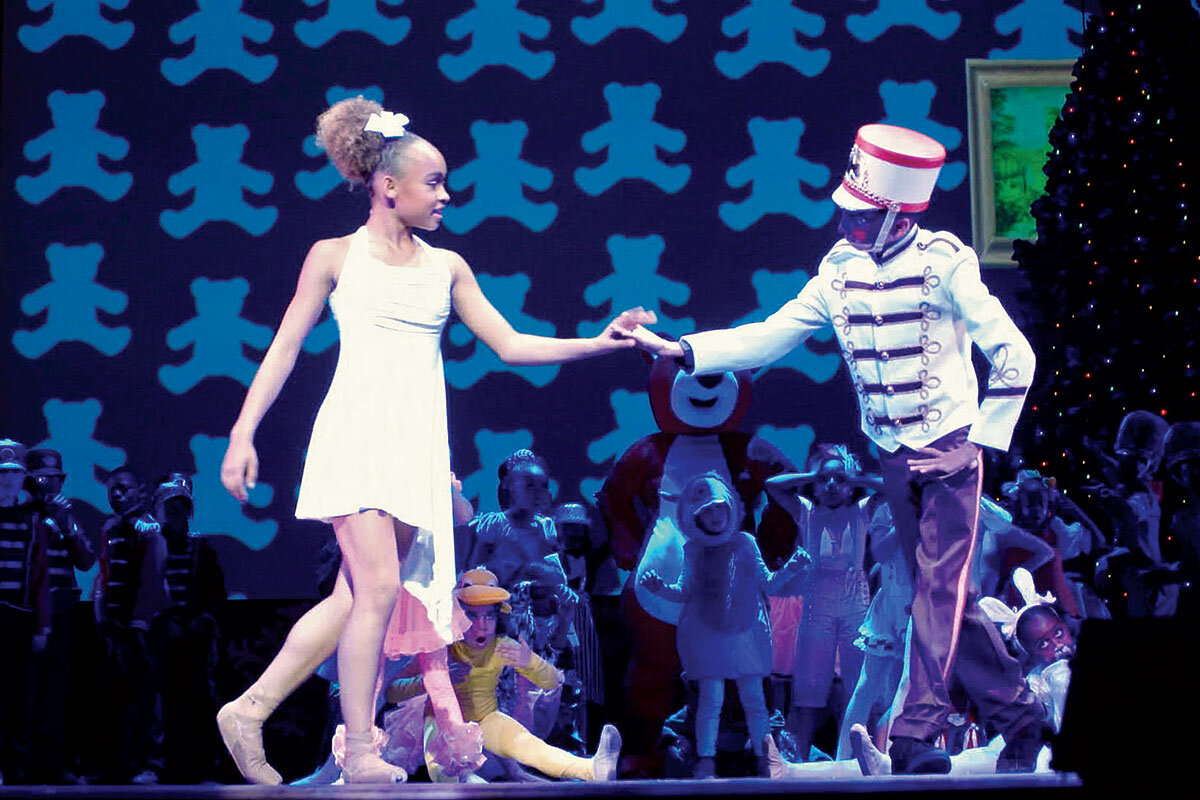

For us, by us

Award-winning performer and director Debbie Allen reinforces the idea that ŌĆ£The NutcrackerŌĆØ can be transformed to better represent and serve the community. In ŌĆ£Dance Dreams: Hot Chocolate Nutcracker,ŌĆØ a behind-the-scenes documentary now streaming on Netflix, she auditions, rehearses, and provides tough love to her multicultural cast, which includes students from Debbie Allen Dance Academy, as they prepare for performance day.┬Ā

One of the dancers who got her start in Ms. AllenŌĆÖs school, Kylie Jefferson, says in the documentary that she has never seen a ŌĆ£regular Nutcracker,ŌĆØ which she likes because this vision of diversity is the only life she knows.

Wayne ŌĆ£JuiceŌĆØ Mackins, who was the original Nutcracker prince in the ŌĆ£Hot Chocolate Nutcracker,ŌĆØ says in a phone interview that Ms. Allen was ŌĆ£focused on reflecting what life actually is because we donŌĆÖt live in a homogeneous enclave.ŌĆØ For Mr. Mackins, this means being willing to reach out to other people and cultures rather than make assumptions. For example, Ms. Allen asks the tap dance star Savion Glover to create a dance for her ŌĆ£Nutcracker.ŌĆØ Rather than approximate her idea of what tap dance was, she went to a qualified source. That is the essential takeaway from the documentary. Rather than approximate another culture, invite people from that culture to share their input.┬Ā

The hope is that these reimaginings can retain the spirit of ŌĆ£The NutcrackerŌĆØ while bringing the community together to create something that feels more inclusive and authentic.┬Ā┬Ā