How George Floyd and #BlackLivesMatter sparked a street art revival

Loading...

| Boston

Street artists often paint on walls in order to tear them down.Ģż

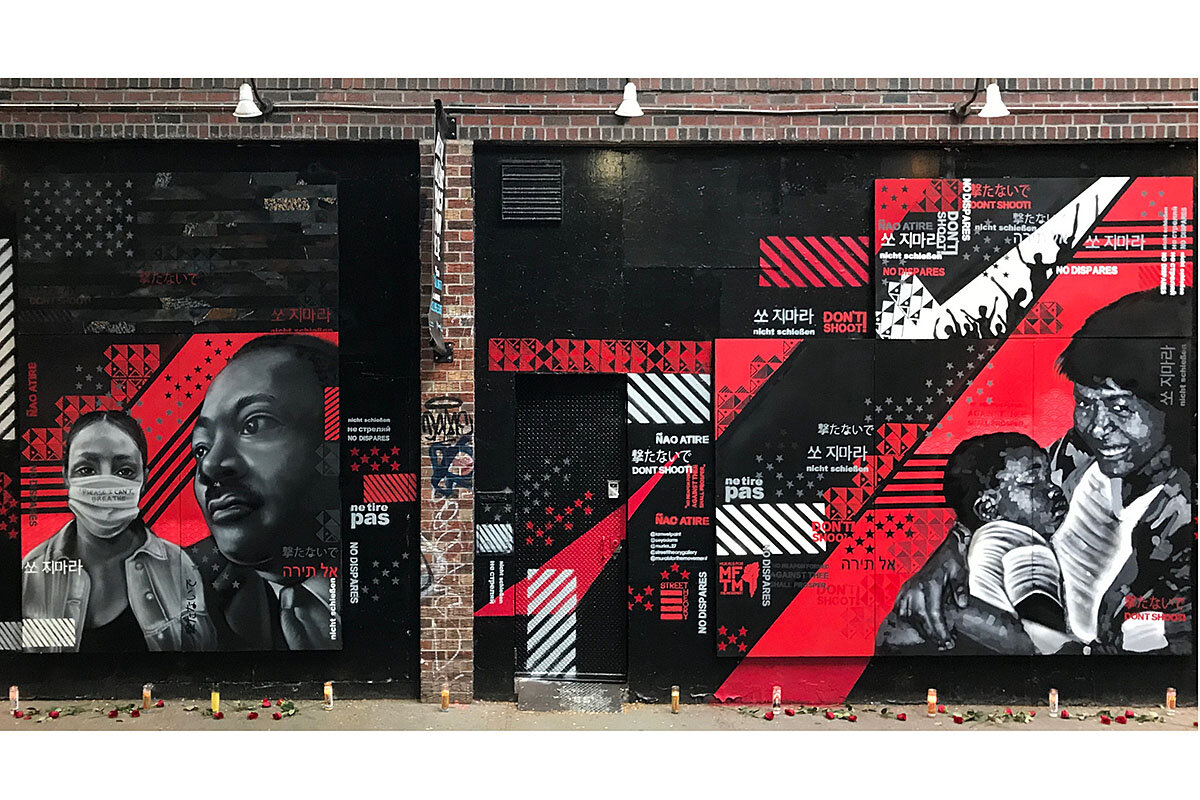

Following the death of George Floyd and subsequent protests, muralists have picked up aerosol cans and paintbrushes to convey a need for change. Dozens upon dozens of murals of Mr. Floyd and other victims of police violence have sprung up on walls across the United States. Street artists are taking advantage of the immediacy of this most public of art forms to beautify drab urban spaces and reach the hearts of viewers.Ģż

Theyāre also continuing a rich artistic tradition of muralists whoāve used outdoor canvases to convey political messages. During the New Deal, for instance, Diego Riveraās murals highlighted the toil of industrial workers. But it was the arrival of spray cans that truly democratized street art and empowered a young generation to express itself. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the burgeoning punk and hip-hop scenes in Philadelphia and New York spurred teenagers to both deface and decorate subway trains and urban spaces with stylized slogans and signatures. Elegant forms of stylized graffiti, the progenitor of street art, started to emerge from spray paint scribbles.Ģż

Why We Wrote This

As movements for racial justice have rocked the country, murals have become a striking part of the protest ā and healing ā process. Our culture writer talked to five street artists to understand whatās prompting the revival of this political art form.

āThis is an art form that was started by Black and brown and Latinx teenagers in their marginalized communities because of the injustices that theyāre facing and because that was their outlet and their voice,ā says LizaĢżQuiƱonez, founder of , an initiative to rebuild communities in Boston, New York, and Los Angeles with uplifting murals by Black and other minority artists.

Long before Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring hung pieces of art in ritzy galleries to decry racism and the devastation of AIDS, they were street artists. Mr. Haringās 1986 anti-drug mural, āCrack Is Wack,ā in East Harlem remains New Yorkās most famous mural. More recently, the likes of Shepard Fairey (most famous for his Barack Obama āHopeā poster) and the mysterious Banksy (most famous for his playful pranks) have become global icons through their Instagram-shareable street art that advocates for social justice and other causes.Ģż

Not all street art is political, of course. Subjects range from the prosaic (portraits, landscapes, animals) to the imaginative (surrealist trompe lāoeil optical illusions whose meanings are as elliptical as Salvador DalĆās mustache). But the global art form remains a visible form of public protest in places such as Mexico City, Beirut, Hong Kong, Johannesburg, Santiago, and cities across America.Ģż

āAll these different movements are quite specific in their political concerns, but I do feel that itās fair to put them under one political umbrella, which is artists are looking for an audience, eyeballs, really, when it comes to drawing more attention to their political concerns,ā says Liz Munsell, co-curator of a new exhibition, āWriting the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation,ā at Bostonās Museum of Fine Arts. āArtists throughout history have been at the forefront of introducing very progressive social ideas into society and paving the path towards normalizing them.ā

āItās a voice for the voiceless,ā adds Sami Wakim, who runs the Street Art United States website, a hub dedicated to worldwide murals that instill a sense of hope, as well as history, through creative expression.Ģż

The Monitor reached out to five professional street artists to hear their stories. Reliant upon commissions, grants, and sponsorship from nonprofits and businesses, they approach murals from different art traditions (several of them employ graffiti nicknames). But what they share is that theyāre using murals to counter racism and denounce police violence by presenting affirmative images of Black people.Ģż

Rob āProBlakā Gibbs

He starts painting at 5 a.m., racing against the sun. From atop his forklift crane, Rob āProBlakā Gibbs ā one of Bostonās foremost graffiti and street artists ā resumes work on a multistory mural at the Madison Park Technical Vocational High School. As dawn glistens on nearby skyscrapers, he observes natureās daily shift change as bats cede the sky to birds. The artistās thoughts flit to his 2-year-old daughter as his spray cans rattle and spit. She inspired his mural of a young Black girl floating above the ground with wings on her sneakers.Ģż

Mr. Gibbs says the message of the mural is, āThe future is in our children. Regardless of your culture. If you are a child to this world, you are contributing to a better future.ā

He believes that the timing of the image coincides with the Black Lives Matter protests.

āI know a higher power is playing into everything we do,ā the veteran graffiti artist says later, sweat beading on his forehead during a midmorning break. āIām here to give a positive balance. Not to say Iām not hearing whatās happening or that I donāt have an opinion, but while the young people are speaking, Iām just letting them know, āYo, I hear you.āā

Mr. Gibbs,Ģżan artist-in-residence at Bostonās Museum of Fine Arts, co-founded Artists for Humanity, a studio to mentor young artists, most of whom are minorities. Today, an art class of teens hovers near the mural as Mr. Gibbs tops up a paint canister and dons a respirator that looks like the bottom half of Darth Vaderās mask.

āIf youāre giving the youth the ability to open their mouth to say something and itās on a platform to be seen and heard? Letās go man,ā says Mr. Gibbs. āLetās lean into these conversations. Letās see if we can do better if we just teach each other to do better.ā

Thomas āDetourā Evans

In Denver, Thomas āDetourā Evans sees canvases where ordinary people see impassive hunks of stone, brick, and concrete.Ģż

āI saw a wall and it spoke to me and said it needs a George Floyd on there,ā says Mr. Evans, who branched out from ambitious art museum exhibitions built around his paintings to street art in 2015.Ģż

Once heād received permission to paint the surface from the buildingās owner, his friend Hiero Veiga came over to help. Mr. Evans created the lower part of Mr. Floydās face, rendering it with impressionistic color. Mr. Veiga, a distinguished graffiti writer, muralist, and fine artist, painted a more realistic skin tone. The effect was to make it seem as if life was being breathed back into the body.Ģż

Soon after, the pair were offered spaces to memorialize two other people who died recently from police violence, Breonna Taylor and Elijah McClain. Mr. Evans calls the series a āSpray Their Nameā campaign. Like all street artists, he shares his work on Instagram.

āWe are visual historians of what is happening today,ā says the artist, who is the subject of the documentary āDetour,ā on Amazon Prime. āAs many of the marches die down and thereās more distraction for people as things open up ... I like having that as a reminder of whatās really important.ā

Sophia Dawson

A strikingly different type of Black Lives Matter portrait was recently unveiled across the street from the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. Sophia Dawson painted a mural depicting Eric Garner, the victim of asphyxiation by a police officer, as a child. He poses smiling alongside his sister, Lisha, and his brother Emery. Titled āFor Gwen,ā the mural is dedicated to the mother of Mr. Garner.Ģż

āA motherās loss of a child is a universal loss,ā explains Ms. Dawson, whose long-standing activism for criminal justice reform stems from watching documentaries in college as well as her own motherās incarceration. āI was really trying to tap into the hearts of people that donāt care and donāt see and that donāt feel, because I think theyāre blinded in a way. And Iām hoping that my art will lift the veil off their faces so that they can see things the way I see it.ā

Ms. Dawson, a fine artist who is entirely new to street art and using spray paint, also collaborated on a mural where she painted Mr. Floyd as an infant in the arms of his mother.ĢżIn another Black Lives Matter mural in Foley Square in Manhattan, Ms. Dawson filled the āLā in the phrase with portraits of mothers whose children have been killed by police.Ģż

āI believe my gift is from God, so I use it as a form of service,ā says Ms. Dawson, who teaches art classes at Rikers Island, a jail for New Yorkers, most of whom are awaiting trial. āWeāre meant to bless other people, to heal other people, to liberate other people.ā

Cedric āVise1ā Douglas

Long before he went to college to become a professional designer, Cedric āVise1ā Douglas learned his craft with quick, furtive paint strokes of aerosol cans on the streets. Scanning other peopleās sneakers for telltale aerosol splatter, he joined a crew in Boston and tagged walls as Fanes, a playful twist on the word āfinesse.ā Recognizing his talent for art was, Mr. Douglas says, akin to discovering he possessed a superpower.Ģż

āThe cool thing about graffiti was it was like my second superhero outfit,ā he says. āIām Cedric Douglas by day, but at night Iām Fanes. So it was like people didnāt know who you were. But you had something that you knew you were doing that no one knew.ā

Not even his own family knew about his pastime. When Mr. Douglas was arrested for elaborate artwork on a derelict basketball court, the police heād fled from during a foot chase were far more genial than his livid mother. Compounding his motherās ire: The Boston Globe covered the incident.ĢżIndeed,ĢżsomeĢżstreet art is considered vandalism under the law and may be punishable with fines or imprisonment if people are caught by the police.ĢżBut Mr. Douglas knew that his interest in graffiti had steered him away from worse paths. After college, he and his partner Julia Roth started their own mobile art vehicle, dubbed the Up Truck, to mentor children.

āWeād go around teaching people how to be creative,ā he says. āSome of the things we do teach is spray paint, which is kind of ironic since I got arrested for using it.ā

Mr. Douglas has painted many pieces protesting violence, including portraits of nine victims of the 2015 mass shooting at a church in Charleston, South Carolina. For a recent art project, Mr. Douglas created yellow caution tape featuring the last words of Black people killed by police, including Mr. Garnerās āI canāt breathe.ā When he handed out reels of the tape to Black Lives Matter protesters in June, the front page of The Boston Globe featured a photograph of someone holding a strip with the words āDonāt shoot.āĢż

āA lot of the work I try to do is paint Black men and women in a positive light,ā says Mr. Douglas, who wasĢżnominated for the Ad Club of Bostonās 2016 Rosoff Award for individuals changing the city through diversity and inclusion. āOne of the issues we have with racism is that a lot of people have a negative perception of Black men and women. A lot of people just arenāt around a lot of different cultures. Boston is very siloed, and thereās Black neighborhoods and thereās white neighborhoods.āĢż

Robert VargasĢż

For much of the coronavirus shutdown, Robert Vargas has been working on one of the worldās most ambitious ā and dangerous ā pieces of art. Heās been painting āAngelus,ā one of the worldās largest murals, entirely freehand on the side of a 14-story Los Angeles building. Ascending two stories on the swaying scaffolding can feel like an additional 1,000 feet, says Mr. Vargas, who explains that āAngelusā celebrates ethnic diversity in an inclusive city. But when the Black Lives Matter protests came through his downtown neighborhood, the internationally known fine artist came back down to earth. He watched rioting and looting break out while standing in front of another of his murals, āOur Lady of DTLA.āĢż

Days later, when the ransacked Starbucks across the street from him erected wooden boards to cover its broken windows, Mr. Vargas saw an opportunity to turn a āblack eye for our community and a bit of an eyesoreā into a positive message. He used the planks as a canvas to paint the word āJustice.ā The word is split into two. Mr. Floydās eyes sit between the two fragments.

āThe symbolism there is that he is the bridge to justice,ā says Mr. Vargas. āWhat I wanted to do was create something that would, of course, show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, but also be able to create an image that would show that we are a resilient people.āĢż

Mr. Vargas went even further. After observing artists painting the slogan āBlack Lives Matterā in gigantic letters on streets across the country, he decided to make a statement of his own. He painted the words āChange,ā āPeace,ā āUnity,ā and āLoveā over the four crosswalks directly beneath his high-rise studio. He named the piece āIntersection of Introspection.āĢż

āYouāll be able to take one of these roads, make a left, make a right, and then find the Black Lives Matter intersection somewhere else,ā says Mr. Vargas, a fine artist in the classical tradition. āIf youāre down with Black Lives Matter, then thatās the destination. If you donāt understand Black Lives Matter, then thatās the origin.ā