Gatekeeper for clean sports

Loading...

| Los Angeles

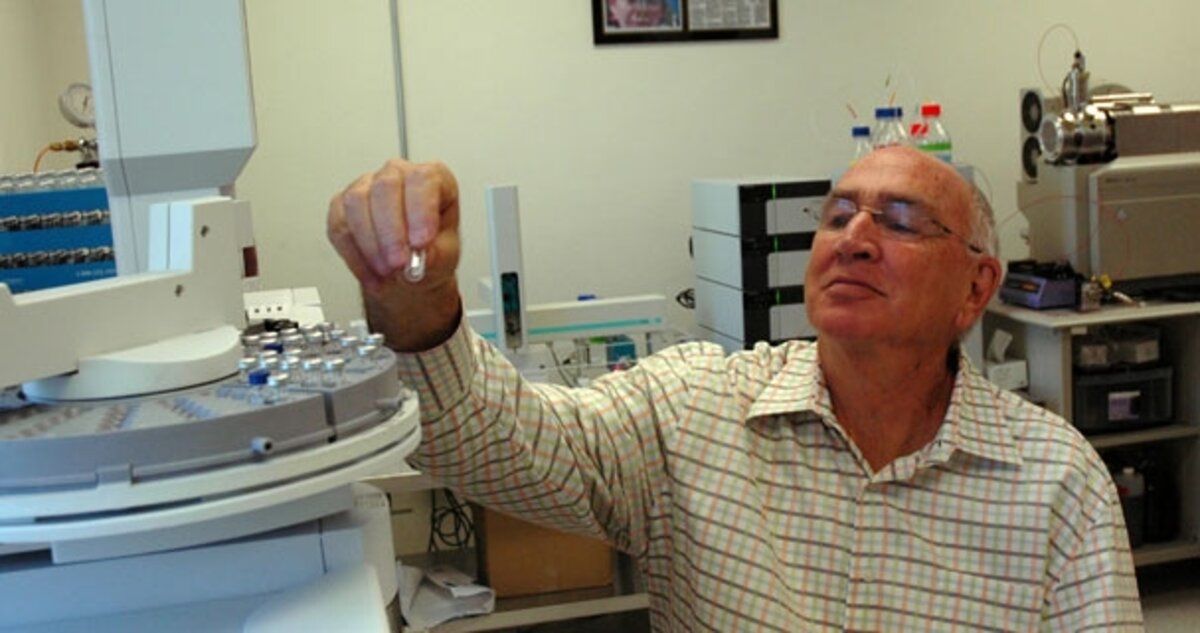

The back lot behind Barry’s Plumbing doesn’t look like a fitting place for one of sport’s greatest sleuths to set up shop. The narrow alleyway is unmarked, as is the plain brick building – a former clothing manufacturing shop. Google Maps will not get you here.

But then again, fame and fancy office space aren’t what Don Catlin is after. It’s illegal performance-

enhancing drugs he’s targeting.

Antidoping czars plead for his help. Dopers dread it. His team was, after all, the one that cracked the designer steroid at the heart of the California BALCO scandal – arguably the biggest doping ring unearthed since East Germany’s program, involving more than a dozen athletes including track star Marion Jones and baseball giant Barry Bonds.

“[Chief BALCO investigator] Jeff [Novitsky] called me one day,” recalls Dr. Catlin, chuckling. “He’s reading me an e-mail that he lifted from somewhere and it said something like, ‘Catlin’s on to it [the drug]. Better move to another one.’”

One of the world’s most respected names in the science of doping, Catlin spent 25 years pioneering a global antidoping model in the Olympic lab at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA). He oversaw the Olympic drug-testing labs at the 1984, 1996, and 2002 Games, and is playing a supporting role in Beijing.

Still, despite his success as one of the cleverest cats in a Tom-and-Jerry pursuit of dopers, Catlin has become convinced that the paradigm on which he based his work for two decades is faulty: It’s the clean athletes – not the dirty ones – who deserve his services.

•�Ģ�Ģ

It all started when a coach burst into Catlin’s office nearly three decades ago. US sprinter Evelyn Ashford, a medal favorite for the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, was drawing suspicions of doping because she was beating East German “she-males.” Pat Connolly was in his doorway, begging him to prove them wrong.

“What she wanted me to do was test Evelyn and stand up and say, ‘She’s clean,’ ” says Catlin, who was then setting up a drug-testing lab for the Games. “She didn’t really understand how complex that would be to actually execute it.”

In fact, drug testing was so primitive then that Catlin couldn’t even detect a steroid he had knowingly taken as an experiment. Now he and fellow researchers worldwide have developed a sophisticated battery of tests for dozens of drugs. One can even prove that an athlete doped without needing to know what drug was used.

Yet even with all this savvy, the sports world is in something of a nuclear arms race. Almost as quickly as scientists can devise new tests, pharmaceutical companies pump out new drugs that dopers can abuse – or that allied chemists can tweak to foil current tests.

“Sometimes you can add a hydrogen or carbon molecule that would modify the weight of the product, and then you can’t scan for it,” says Sabrina Benchaar, whom Catlin hired in April at his new firm, Anti-Doping Research (ADR).

Dr. Benchaar’s current project shows how difficult the task can be. She is trying to develop a way to detect human growth hormone (HGH) in urine samples. Though the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has piloted a blood test for HGH, two of the biggest professional sports organizations – Major League Baseball and the National Football League – have said they’re waiting for more scientific validation, and players’ unions have opposed blood testing. If researchers could develop a foolproof HGH urine test, it could do much to clean up the dugout and the sidelines.

It isn’t just a matter of slipping a slide under a microscope. Human urine contains more than 1,500 proteins. Even Catlin admits the HGH test “is probably the most difficult test in this whole field.” Benchaar, however, is convinced it can be done – maybe even in six months. She describes the intricate work of one of the lab’s machines, a $1 million “Orbitrap,” that dissects chains of amino acids as if throwing a pearl necklace at a wall. The smaller strands, or “pearls,” can then be identified and synthetic proteins singled out.

In contrast to HGH testing, the process for detecting known steroids and amphetamines is far more developed and precise. It begins with an official collecting urine samples from athletes at competitions or on surprise visits, and marking them with anonymous codes.

When samples arrive at the lab, researchers submit them to rigorous chemical testing, ultimately producing printouts that look like saw-toothed mountain ranges. If the “ridge” lines match up with those of a known drug, then it’s considered a positive.

More subjective is the urine test for the endurance-booster EPO. Catlin scrolls through images on his computer that look like X-rays of rattlesnake tails. Standing behind his chair, Dr. Caroline Hatton – his quality-control czarina for more than two decades – explains how technicians evaluate the darkness of the strips, comparing them with samples known to contain EPO and with ones that don’t. But it’s still an imperfect science. In June, a Danish study revealed that two different WADA-accredited labs – one of which faulted the study’s methodology – came up with different results for the same samples, adding to the debate over EPO testing.

All this is expensive, too. Catlin estimates that it cost as much as $500,000 for his team to develop a test for the BALCO steroid THG. Machines start at $80,000. To thoroughly vet one athlete once can run up to $2,000.

And there can be glitches. Some drugs become undetectable even as they continue enhancing performance. Athletes have found bizarre ways to hide clean samples and provide them in place of their own. They can also wet a finger with an enzyme that breaks down drugs, and let it run into their sample. Catlin suspects that may be why Marion Jones’s A sample was a “flaming positive” for EPO while her B sample, taken at the same time but tested later, was a “flat negative.”

After 25 years of testing, Catlin has come to the conclusion that “science can’t solve all the problems. For me – who ... believed we could do it just with doping control and testing – to say it’s not working is a bit of a change.”

•�Ģ�Ģ

By most measures, Catlin has every right to hang up his beakers and spend his days biking up the dirt tracks near his mountain home. But he remains as devoted to his work today as he has been in the past. When his wife passed on in 1989, he got up at 3 a.m. daily, returning home midafternoon to raise his teenage boys.

“He’s never been in this for sport,” says son Oliver, now vice president of ADR. “He’s really in it to build that integrity.”

Now freed from the task of administering UCLA’S 50,000 annual drug tests, Catlin is settling in at ADR to do what he loves: “tinker with ideas.” And his favorite one goes back to Ms. Ashford, the sprinter: What’s being done for clean athletes? “I’ve always felt that we put too much emphasis on dirty athletes and too much money into finding the last little molecule of some abstruse drug somewhere,” he says. “Ever since [Ashford], I’ve had it in mind to try to find ways to do things for athletes who really care.”

So for the past decade, he’s been fine-tuning his “Volunteer Program.” It would turn the tables on doping, putting the onus on athletes to prove they’re clean rather than on scientists to prove they’re dirty. Athletes would be tested often, yielding a biological profile. Over time, if testing revealed a spike in values that the athlete could not explain, he or she would be dropped from the program.

Several similar initiatives have cropped up recently, including one run by the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) in the run-up to Beijing. USADA chief Travis Tygart credits Catlin. “Don has been instrumental in not only the pilot testing program, but where things are in antidoping today,” he says.

While Catlin lauds Mr. Tygart’s pilot program, he’s concerned that overall the antidoping establishment is too busy defending its system – “a lot of PR, handwaving” – to ask whether it’s the right model for success. But he’s optimistic that sports can be cleaned up – somehow: “Can we achieve it with what we’re trying to do? I’m not sure, but I hope so. I’ve built my life on it.”

• Previous installments in this series ran July 14, 21, and 28.