Energy use falls when neighbors compete

Loading...

One of the best ways to save energy and cut carbon emissions isn’t the much-touted “smart grid,” low-watt light bulbs, or high-tech appliances – it’s a little neighborly competition.

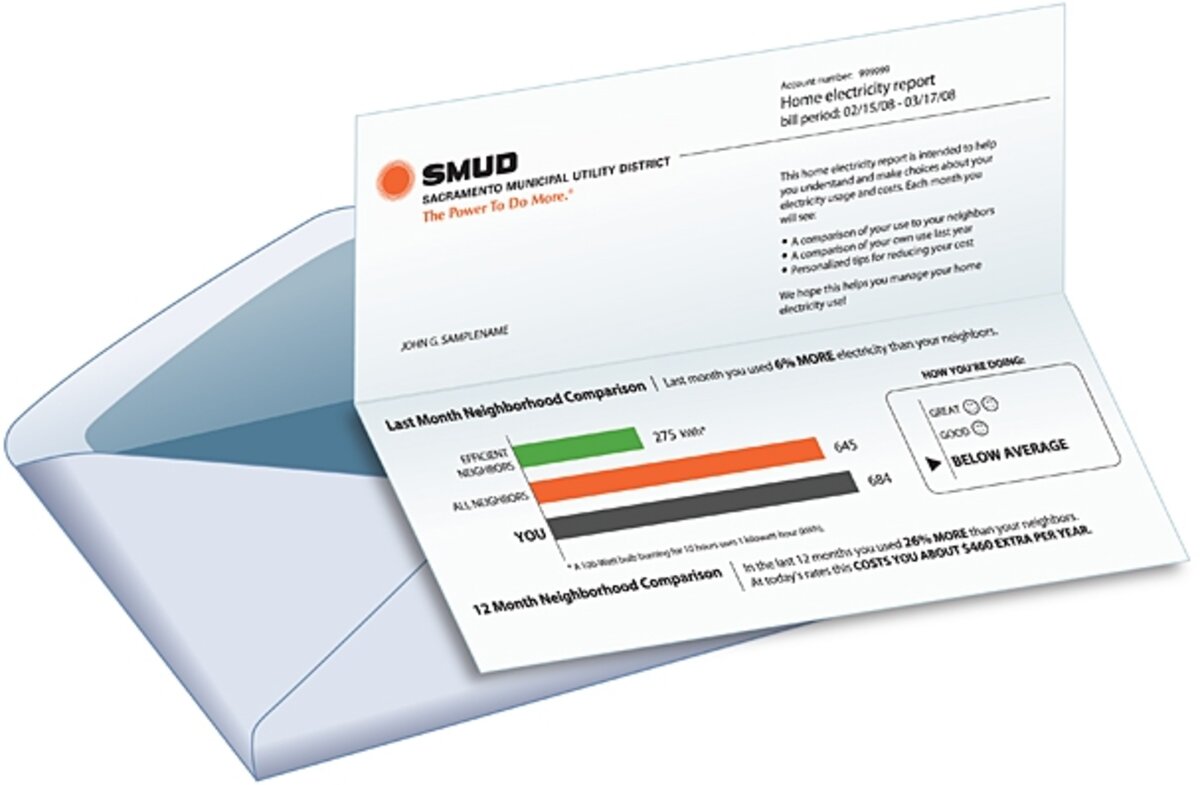

Just ask Sacramento resident Kat Kelly, who last year began getting a new “home energy report” from her utility company that compared her family’s electricity use directly with her neighbors’.

On the report, one bar chart rated her family’s electricity use against the average of 100 neighbors with similar sized houses – and also of her 20 most energy-efficient neighbors. The report had three rating levels: “below average,” a smiley face for a “good,” or two smileys for a “great!” average.

A self-described “competitive person,” Ms. Kelly says she was shocked to learn that her family not only failed to get a smiley, it received a “below average” rating. That same day, she began turning off lights, changing the thermostat, and switching off her power strips – anything to save juice and win future smiley faces.

“It got my competitive spirit going,” Kelly says. “I wanted to be one of the

energy conservers in my neighborhood.”

Her reaction is not unusual. Some say it’s the power of competition – the desire to keep up (or in this case “down”) with the Joneses. Others say it’s just logical

decisionmaking. Whatever it is, the simple act of informing residents about their neighbors’ power use can be like firing a starting gun in a race to save energy, researchers say.

Improving residential energy efficiency is critical to combating climate change since it equals about 35 percent of total US energy use and 15 percent of total US greenhouse-gas emissions, federal data show.

Over the decades, Americans have become more frugal with energy. But thousands of tiny personal choices around the house could substantially cut energy use.

How much? The “human dimension” in energy consumption could whack household energy use 22 percent nationwide – a 12 percent reduction in overall US energy consumption, according to a new American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE). By comparison, all solar, geothermal, and wind power consumed last year amounted to about 1 percent of US energy use.

Yet human impact has been largely ignored by electric utilities. Instead, their efficiency programs have focused mostly on “widget based” programs that pay rebates for efficient appliances, for instance.

But with new state laws boosting efficiency requirements, widget programs are reaching their limits. That’s pushing dozens of utilities to experiment.

“Energy is very much an invisible commodity for most people,” says Karen Ehrhardt-Martinez, an ACEEE researcher. “It’s not like pumping gas into your car. It flows invisibly into the house, and you don’t know anything until you get the bill. We need people to have all the information so they can make better choices.”

Widely used on college campuses today to combat binge drinking, a “social norms” approach surveys and then publishes data to make plain to students that campus drinking levels are (almost always) far lower than they think. Less binge drinking is the frequent result.

The social-norms approach has also been applied to curb gambling and environmental pollution, and to promote health choices. Online retailers use it to encourage purchases when they tell visitors that “customers who bought the items in your shopping cart also bought....”

“The middle is a magnet for behavior,” says Robert Cialdini, professor emeritus of psychology at Arizona State University and a pioneer on the social-norms impact on energy use. “What you find is people who are in the outlying areas as violators of the desirable behavior will move to the middle when they learn they’re outliers.”

That’s what the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) in California found when its social-norms pilot tests over the past year cut energy demand by 2 percent – just by telling folks how their energy use compared with their neighbors’. That drop may sound puny, but SMUD saved 9.5 billion watt-hours, equal to the electricity use of 1,000 average homes for a year.

The Kelly family, for instance, cut its energy use 10 percent – and have yet to win a smiley face. But Kat Kelly and thousands like her have SMUD officials smiling.

“Even those folks who received the ‘You are below average’ message from us saved, and actually saved the most of any other group,” says Alexandra Crawford, a SMUD project manager. At least two dozen utilities nationwide are experimenting with saving energy this way.

“You aren’t born knowing what your utility bill should be or ‘Am I using more than I need to?’ ” says Daniel Yates, president of OPOWER, in Arlington, Va., which analyzes SMUD customer energy use and pioneered using smiley faces. “You know people think a Prius is a good thing and a Humvee is bad,” he says. “Well, a lot of Prius owners have Humvee houses and don’t even know it.”

While OPOWER focuses on developing reports like those SMUD sent by mail, others are putting it on the Internet.

At Efficiency 2.0, a New York-based software provider to utility companies, Andy Frank’s team is working with the Western Massachusetts Electricity Company to create a Facebook-like community where people can help one another save energy and compare results in a friendly, yet competitive way.

Online comparisons come with frowny or smiley faces and also give people highly customized tips about how they can reduce their energy use. It offers, for instance, a calculator tallying myriad decisions – take shorter showers, adjust thermostat settings, or hand-wash dishes.

“We’re like Weight Watchers for your energy use,” says Mr. Frank, Efficiency 2.0’s executive vice president for business development. “Most Americans would like to lose weight, but they don’t do it because they don’t get feedback. We provide that feedback [to cut energy use].”

Wendy Penner loves that feedback. Her website profile tells the community of users that she has chosen to hand- wash her dishes in cold water, saving 238 pounds per year of carbon dioxide and knocking $45 off her energy bill.

When those results didn’t satisfy her, Ms. Penner further pledged to dial down her water heater temperature from 135 to 115 degrees F., saving 626 pounds of CO2 and $92 worth of fuel annually. Overall, she’s lowered her personal energy use by 1.4 percent and is on track to save $190 per year and 1,120 lbs. of CO2.

That hasn’t won her a smiley face yet, though. Until recently, her page sported a frowny face because she’s doing better on energy use than only 25 percent of the community at large. She would like to be competing against a group of “energy friends,” but doesn’t have any since the site has only been running a month.

“This is really a very powerful tool and I like it a lot,” Penner says. “The motivation from it is pretty strong. People really don’t like getting the frowny faces.” (In fact, SMUD and others have nixed frowny faces after some negative reactions.)

Commonwealth Edison, a Chicago-area utility, is pleased overall with its program, which is similar to SMUD’s.

“In a few cases we’ve been accused of being agents of some secret service spying on them,” says Val Jensen, vice president for marketing and environmental programs for Commonwealth Edison. “But that kind of reaction has been in the low single digits. Only one homeowner has said, ‘Stop sending me this.’ ”

When Dennis Boland, a stock-index trader from Glenview, Ill., got his new home energy report from Commonwealth Edison last month, he was aghast.

The report showed that the 20 most efficient homes in Mr. Boland’s neighborhood used about 587 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per month, while his group of 100 neighbors used 1,150 kWh per month. And Boland’s home? Try 1,987 kWh monthly – 92 percent more than the average.

“My first observation when I read the report was: ‘I am a pig!’ ” he says. “I knew I was paying a lot every month for electricity, but I thought everyone was. I didn’t know I was such a glutton.”

Even though it made him feel guilty, Boland says he was also grateful. Now he’s changing his thermostat setting to reduce his air-conditioning load and looking for other ways to save energy – and money.

He’s eager to see the next report to determine if he’s off the “below average” list. “I hope more power companies will pick up on this,” he says, “and not be afraid to tell their users: ‘You’re below average’ or maybe, ‘You’re a pig!’ ”

[Editor's Note: The original version of this article referred to OPOWER by its previous name, Positive Energy.]