In these bilingual classrooms, diversity is no longer lost in translation

Loading...

| Boston and Somerville, Mass.

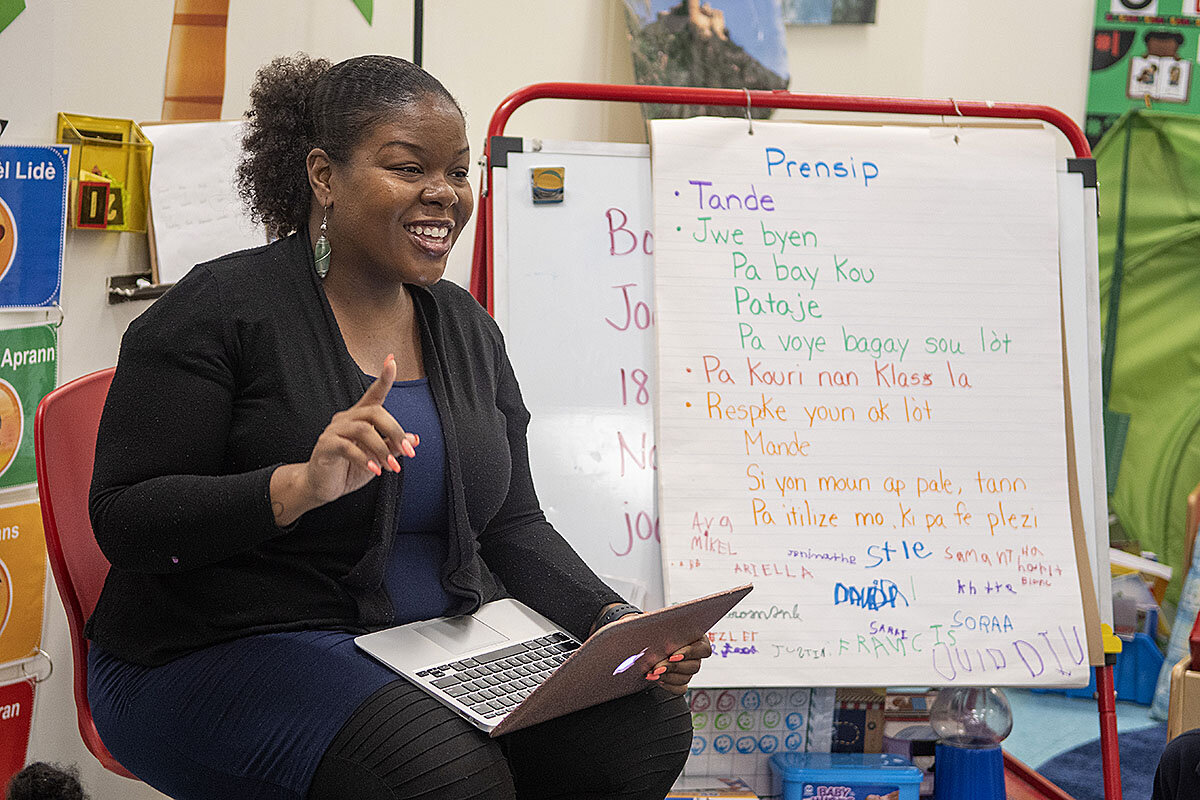

“Tonton Bouki!”��shouts Priscilla Joseph, a kindergarten teacher at the Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy at Mattahunt Elementary School in Boston. “Eya eya!” her class roars back, swaying in a circle at the front of the classroom.

“N’ap mache!”��Ms. Joseph calls out. “Mache konsa!”��they reply, nearly falling over each other giggling. Tonton Bouki, the subject of their song, is a mischievous character in Haitian folklore.

The Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy is a one-of-a-kind bilingual kindergarten program here in Mattapan, an immigrant-dense neighborhood at the city’s southern border. It’s the country’s only Haitian Creole��two-way dual immersion program at this level.

Why We Wrote This

When a second language is seen as an asset, not a burden, it can lead to a powerful byproduct: integration. This is part of an occasional series on efforts to address segregation in schools.

In Joseph’s class, Haitian and Haitian-American students mix in equal numbers with kids who have no direct connection to the Caribbean country. “No one is different here because they speak a different language,”��she says.

With immigration debate at such a fever pitch in the United States, you might think bilingual education would be stalled. The usual routine, experts say, is like a pendulum: When support for immigration drops, so do funding and policies that bolster multilingual classrooms. And vice versa.

But despite some prominent anti-immigrant sentiment in the US, one form of bilingual education is actually gaining steam. Two-way dual immersion, which combines fluent English speakers with English language learners (ELLs) is taking off.

“These two-way programs with English-speaking kids are just exploding all over the country. Now it’s an advantage for the middle class, for English-speaking parents to have their kids in a program like this. So it has changed the dynamic,”��says Patricia Gándara, professor of education and co-director of the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles.��

That explosion of support signals a shift in how educators across the political spectrum think about multiculturalism. The traditional approach would take ELLs and drill down on language lessons until they could hold their own in English-only classes. Two-way immersion, on the other hand, celebrates students’��different cultural backgrounds – and sees a second language as an asset, not a burden.��That line of thinking can lead to a powerful byproduct: cultural and racial integration.

“Two-way dual immersion programs do integrate kids ... It is a natural strength of those programs so long as it’s implemented well,”��says Ilana Umansky, assistant professor of education and policy at the University of Oregon in Eugene.

Bipartisan appeal

The reason behind the new popularity is simple: Learning in two languages has important academic and economic payoffs.��Research suggests that these two-way,��dual-immersion programs, some of which have been around for decades, can lead to that eventually outpace those from peers. Studies also suggest that participation can help close achievement gaps between ELLs and native English speakers. And as demand for bilingual employees in the US��, there’s now more incentive than ever to train a polyglot workforce.

Within the past two years, California and Massachusetts��have both lifted restrictions on bilingual education programs. Only two states still have such measures – Arizona and New Hampshire – although bilingual programs are allowed with special permission.

But it’s not just blue states that are leading the charge on two-way dual immersion. States that are generally tough on immigration are joining in, too. “North Carolina has been ostensibly very anti-immigrant in a lot of its policies but at the same time,”��the state is “one place where there’s a lot of growth in these two-way programs,”��says Professor Gándara.

“So you see these interesting things happening at cross-currents,”��she says.

Of 59 existing two-way dual immersion programs in the��, 22, or about 37 percent, launched in the past three years. The city of�� now has 56 two-way, dual-immersion programs.�� has started more than 200 dual-language programs within the past 10 years, although most are one-way, in which all students are native English speakers.

Opponents of bilingual education often say it keeps immigrants and their families from learning English and assimilating. But with English-fluent students entering these classrooms, that argument is changing.

“Somebody like [Education Secretary] Betsy DeVos, if she’s looking at this issue of bilingualism as something that’s open to all kids and middle-class kids, she’s probably not going to get too involved in this … because there [are] advantages there for middle-class English-speaking kids, for nonimmigrant kids,”��says Gándara.

As for assimilation, observers see changes there, too. In two-way dual immersion, “principals are reporting that [ELLs’] self-esteem is increased and then along those lines, that also allows the non-English parents to be more active in the school community,” says Stephen Kotok, assistant professor of administrative and instructional leadership at St. John’s University in New York.

Integrating classrooms, not just schools

Nancy Uribe, a third-grade teacher at the East Somerville Community School in Somerville, Mass., teaches in , a kindergarten through eighth grade Spanish two-way dual immersion strand of the school. The program is well established – it’s approaching its 20th anniversary next fall.��Every year, Ms. Uribe’s students interview a friend or relative from a different country. Then the children present their research, and families come to watch and eat food from some of the featured cultures.

“I see these Anglo parents with a little bit of Spanish and these Latino parents with a little bit of English eating pupusas��and trying to communicate with body language��... and to see that connection is wonderful,”��says Uribe.����

“The students,”��she continues, “they already have it.”

UNIDOS is the only two-way dual immersion program in Somerville, a dense city just north of Boston with a substantial Latino population. Spanish is in the air here – at bus stops and Mexican restaurants along its main street. But as Boston housing prices climb upward, an influx of English-speaking commuters is reshaping the city’s linguistic diversity, and its school district.

At UNIDOS, the mostly even mix of Latino and non-Latino students spend half their time learning in English and half in Spanish, switching between subjects. Each grade has two bilingual teachers: one a native Spanish speaker and the other a native English speaker. A focus on equal representation helps correct for a problem persistent in even equity-minded monolingual schools.

“Even in successful kinds of racial integration programs a lot of times what happens is the schools look pretty racially diverse but then you walk into the school and the classrooms are not very diverse,”��says Professor Kotok.��“So that's where we were looking at dual language as it can move beyond that and integrate the classrooms.”��

Often, schools take ELLs out of class to focus on English – sometimes for up to four hours at a time, as is the case in . “Spanish-speaking kids or whoever are being pulled out of their classes for their English instruction while their classes are learning math or learning science or learning history,”��says Professor Umansky.��“Those kids end up losing that content.”��

Gentrification challenges

Two-way dual immersion isn’t a magic bullet for integration, say observers��– especially in districts where growing English-fluent populations, who tend to be whiter and wealthier, tilt the community’s demographics.

And that’s where housing reform plays a vital role, explains Gándara. Without measures to keep the neighborhood affordable, the draw of a dual-language program can lead to gentrification. It’s something that Holly Hatch, principal of East Somerville Community School, thinks about often. Housing activists in Somerville have worked to keep property costs from skyrocketing, she says.

In Los Angeles, Gándara has noticed some families keen on getting in to two-way dual immersion programs have even bought houses in qualifying neighborhoods that they then rent out or leave empty while their children enroll.

To prevent ELLs from getting pushed out, schools should commit to maintaining diversity in their student body, says Kotok. Both UNIDOS and the Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy reserve seats for students at different linguistic levels. UNIDOS sorts students into three equally represented categories: English dominant, Spanish dominant, and bilingual. Waiting lists for all three groups are full.��

“Districts need to be very clear on their goal of diversity because [pushing ELLs out]��definitely is a risk and more fluent parents and native speakers try to hoard those seats,”��says Kotok.��“You’re not going to get the full academic and cognitive benefit if you don't have this balance in the classroom.”

Last year, Kotok and his colleagues made additional����for two-way immersion programs hoping to achieve meaningful racial integration, including providing special training for bilingual teachers and securing structural supports for educators and families.

Cultural pride

There’s a subtle point about two-way dual immersion that parents and teachers at both schools often mention. These programs send a message to immigrant groups that their language and culture are valuable to the wider community.��

“Here we all promote what a benefit it is to be able to read, write, and speak a different language and appreciate the differences between people and their cultures,”��says Patrice Hobbs, another elementary teacher in UNIDOS.

At the Toussaint L’Ouverture academy, Joseph has noticed a similar powerful response to the formation of the school, now in its second year. For older members of Boston’s active Haitian community, seeing such a wide interest in the program has moved them.

“They were just so excited to hear that there were kids here in Boston that were learning Creole and some of them that were not even Haitian … And you literally saw their faces light up like, ‘Really?’��And I'm like, ‘Yeah, some of them are not even Haitian at all,’��”��says Joseph.

“Someone taking this much importance in [their] culture gave them a sense of pride,”��she says.

This is story is part of an occasional series,��Learning Together, on��efforts to address segregation.