Native American group negotiates social change – with a checkbook

Loading...

| Ann Arbor, Mich.

Carmin Barker was at first opposed to the school district in Belding, Mich., changing its mascot.

Determined to do her homework, she reached out to half a dozen Native American tribes for their input: the , the , and the in Ontario, Canada, among others. She even reached out to the Michigan Department of Civil Rights.

And then something happened that she hadn’t expected: She changed her mind.

Why We Wrote This

As Native Americans look for better support in schools and more accurate representation in society, a new fund in Michigan is trying a partnership approach that involves give-and-take with communities.

“At the end of the day, it was good decision, as hard as it was,” says Ms. Barker, a mother of six and grandmother of four.

Belding is a small town of roughly 6,000 about 30 miles outside Grand Rapids, Michigan’s second largest city. Conversations about changing the mascot led to some heated school board meetings. And the change seemed costly: jerseys, signage, even shirts that Barker and other parents made on their own – that she now realizes were offensive – would all have to go for good.

The change Belding Area Schools made is one some nearby districts are not yet ready to. “Change is hard,” says Barker. And yet today the issue has virtually dissolved into the ether. “Coming into this football season, it wasn’t a big deal at all…. A year later, it’s like it’s really not an issue anymore.”

The Belding school board voted to change from the Redskins to the Black Knights in the fall of 2016, and in September, it was given a grant of more than $300,000 from the newly created Native American Heritage Fund (NAHF), which organizers are calling a rare initiative. The money will help erase any record of the Redskins as a mascot forever.

The tribe behind the NAHF – – is aiming to prove a point: Be receptive to change, inclusion, and diversity, and there’s a tribe with the money ready and willing to support you with it.

First grants support cities, teens

But the goal of the NAHF goes further than that: to improve the relationship between Michigan’s 12 federally recognized Native American tribes and the communities near them. The NAHF grants were distributed for the first time in September to – ranging from cities to universities to a teen center. About a half a million dollars was dispersed with the help of funds from the tribe’s casino in Battle Creek, Mich., one of the largest in the state. Each year, the tribe will spend $500,000 building bridges with communities across Michigan.

“We understand that there are barriers in the way of people changing, and some of them are financial,” says Judi Henckel, a spokeswoman for the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi.

“The bottom line is we’re not just pointing out problems, we are providing solutions,” adds Jamie Stuck, tribal chairperson of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi and a member of the tribal council for more than a decade. Mr. Stuck notes the band of more than 1,500 members operates a restaurant with a food pantry in the back, part of a partnership with a food bank, in downtown Battle Creek. It also runs three low-cost health clinics.

There are nine bands of the Potawatomi in North America: two are in Ontario, four are in Michigan, and one apiece are in Wisconsin, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Pieces of Potawatomi culture remain a part of our everyday American life. Chicago’s name is derived from a Potawatomi word, for example.

Stuck hopes the fund can be a model for other communities in America. “The problem is, when it comes to mascot issues, when it comes to curricular issues, it’s not just a matter of whether there’s a disagreement, it’s a matter of are there the resources to make things happen,” he says.

The creation of the NAHF required an amendment to the gaming compact with the state of Michigan, as tribal governments must get the state on board for certain decisions. Vicki Levengood, communications director for the Michigan Department of Civil Rights, says in a statement to the Monitor that the fund “is an example of tribal and state government working together to proactively make positive change.”

“The projects these grants will fund,” she continues, “especially when it involves changing a school’s Native American mascot, are vitally important for protecting the well-being of Native American students but can be prohibitively expensive for school districts to afford.”

Changes in imagery

At Lake Superior State University, in Sault Sainte Marie, Mich., nearly 10 percent of the students are Native American. The school will use its grant to further Native American imagery and events on campus. “To embrace our community like this is really important,” says Shelley Wooley, the school’s interim dean of student life and retention.

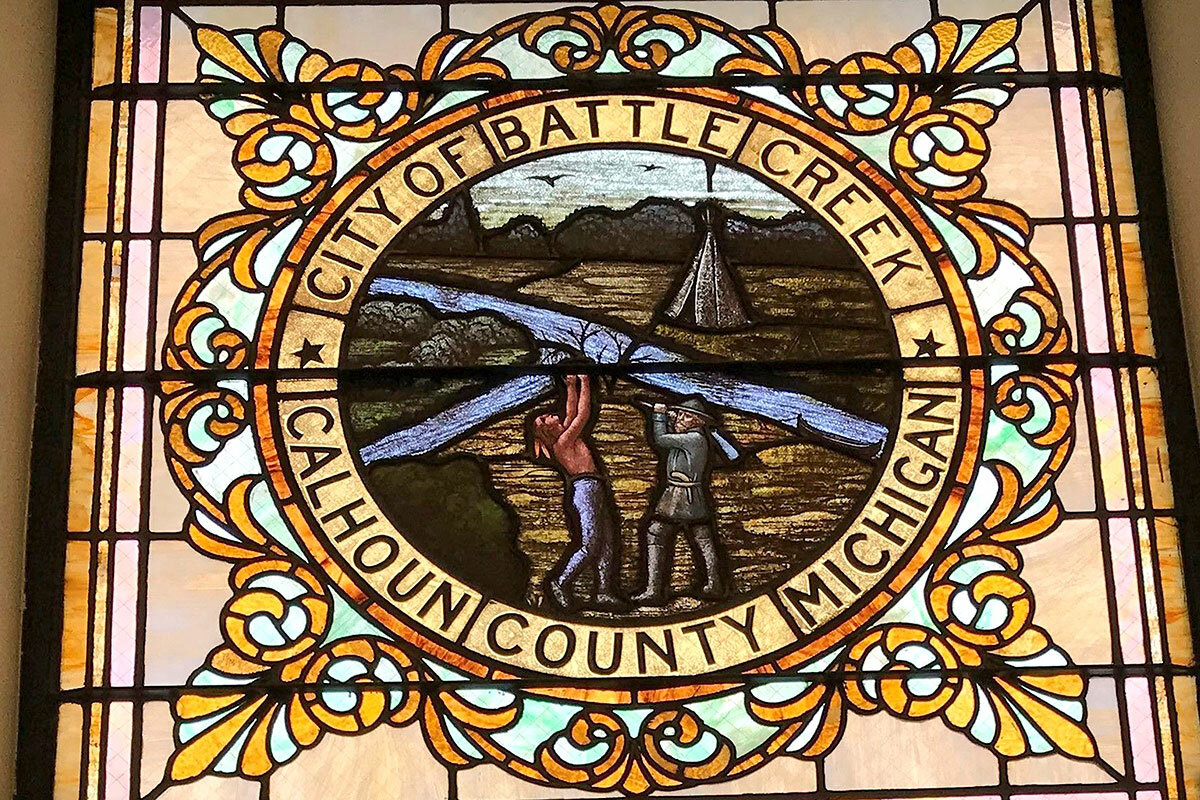

Another recipient of the inaugural Native American Heritage Fund grants is the city of Battle Creek, which received about $3,400 to assist with the removal and replacement of a stained glass window in City Hall depicting a Native American man subservient to a settler.

“I wholeheartedly applaud this effort,” says Rebecca Fleury, city manager for Battle Creek, referring to the work of the NAHF. “I think it is a unique model, I really do, and I applaud the willingness to take these issues head on and provide a mechanism to provide resources.”

Elsewhere, Michigan Technological University, located in Houghton, received $30,000-plus to co-create curricula with nearby Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College in L’Anse. The majority of the college's students are Native American. The joint project, called Ge-izhi-mawanji'idiyang dazihindamoang gidakiiminaan (“the way in which we meet to talk about our earth”), will include coursework in ecology and environmental science and policy.

“This funding is really helpful because there are so many people at Michigan Tech and also in the tribal community that hope to make these connections but don’t necessarily have the time with their own jobs and responsibilities,” says Valoree Gagnon, director of Michigan Tech’s University-Indigenous Community Partnerships and an assistant professor at the school.

In Kalamazoo, following months of public meetings, a work of art on display for decades – known as the Fountain of Pioneers – was removed, with a NAHF grant of $76,765 reimbursing the city for roughly half of its costs after its decision. The fountain depicted a Native American “in a posture of noble resistance,” , but . Remains of the fountain possibly will be moved to a local museum.

“Like anything, the context of the issue is absolutely vital to understanding it,” says Sharon Ferraro, Historic Preservation Coordinator for the city of Kalamazoo. “Times caught up with the fountain…. Society changed around it.”

She says there are many communities in Michigan discussing similar changes that could use financial assistance, such as that which NAHF offered, in the future.

Stuck, the tribal chairperson, is clearly proud of what his band has achieved. “When you can get a state and a sovereign nation on board to do something like this,” he says, “that’s pretty big.”