Mexico takes the battle for gender respect to the classroom

Loading...

| San AndrƩs de BaraƱa, Mexico

When Carmen GuzmƔn Orozco first arrived at the Telebachillerato Comunitario San AndrƩs de BaraƱa as a teaching fellow in 2016, she was taken aback.

It wasnāt the lack of water or internet connection that surprised her at this school of 140 high school students ā it was the whistles.

āIād walk by the classrooms and boys would openly whistle at me,ā says Ms. GuzmĆ”n,Ģża 20-something, second-year fellow with EnseƱa por Mexico (Teach for Mexico), a program modeled after Teach for America that places high-achieving college graduates in public schools here for two years.

GuzmĆ”nās fellowship includes identifying a problem and coming up with a project to address it. The teachers are asked to watch for issues that take kids out of school, but aren't necessarily directly related to education ā such as organized crime ā and to create courses around them.ĢżIn GuzmĆ”nās case, after spending time in this rural community on the outskirts of Silao, Guanajuato, where stereotypes about gender roles run rampant,Ģżshe quickly realized there was a need for a course on gender violence, respect, and human rights.

Such classes are not common in Mexico, where a conservative religious outlook influences classroom culture, and views about gender āĢżoften introduced and enforced in the home ā can be difficult to counter with coursework. But incidents of āmachismo,ā like those GuzmĆ”n encountered, combined with growing violence against women, are lending urgency to the need for more discussion around these topics.

āWomen killed in this country have left a historic imprint on our society,ā says Daniel HernĆ”ndez Rosete MartĆnez, a professor who researches masculinity and violence in education at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute in Mexico City. āMachismo is deeply, deeply ingrained.ā

The conservative, Catholic roots in Mexico mean that few teachers want to recognize ā or broach ā gender, machismo, or the human body in the classroom, he explains. And brushing over these conversations has lasting effects.

Deep thinking in class

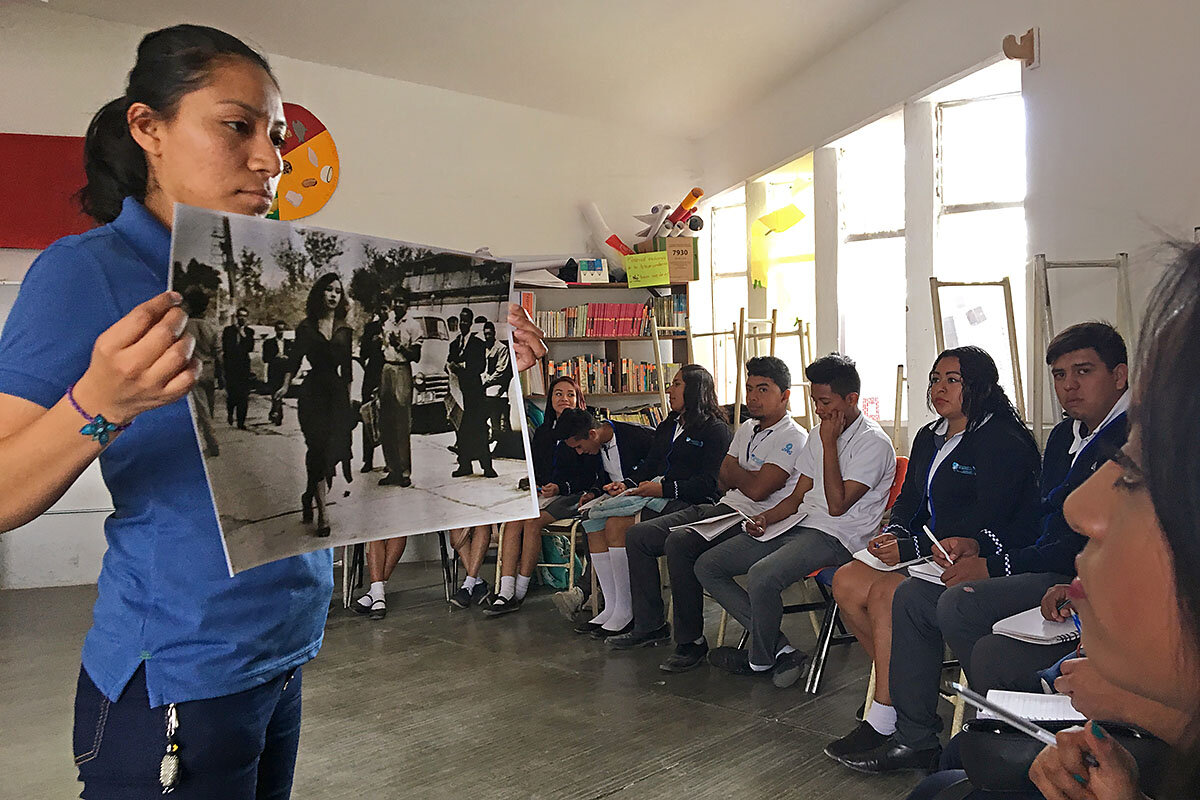

On a recent Friday afternoon, some 30 high school students sit in a circle, examining a black and white photo. The woman in the picture is walking down the sidewalk, and a string of men in the background appear to be calling out to her, heckling.Ģż

GuzmƔn invites the students to describe what they observe.

āShe looks uncomfortable,ā says one student, Lupita, tugging on the collar of her school uniform, a dark blue v-neck sweater.

āI imagine her getting dressed that morning and feeling very confident,ā shares another student across the room, Karla. āBut once she gets on the street, these men are interpreting her clothes as something for them.āĢż

āThe men think sheās beautiful, but theyāre expressing it poorly,ā offers up a young man named Oscar. āItās making her uncomfortable.ā

āDo you think she likes what the men are saying?ā asks GuzmĆ”n. The group responds with a unanimous āno.ā The conversation moves toward the studentsā personal lives: has anyone ever experienced this behavior? āYes.ā Has anyone participated in it? Hands shoot up in the air ā āyes.ā

These second-semester seniors, who started the workshop with GuzmĆ”n last fall, say the conversations with her and their peers, are some of the first about gender, violence, and machismo theyāve had in their 18 years of life.

āWhen the workshop started, I didnāt think women really suffered that much violence in Mexico,ā says senior Juan MartĆn SantibaƱez, adding that he is gay and has always considered himself an ally to his female friends. āBut then I realized, I had been violent toward my female friends on various occasions, making people uncomfortable without really realizing it. Pinching them or insulting them [based on their gender]. Weāre all thinking a lot more about our behavior.āĢż

On average, seven or more women are killed every day in Mexico, according to a 2017 joint report by the Mexican government and the United Nations, which blames increased drug violence for an uptick seen in recent years. In 2016, 2,746 women lost their lives specifically because of their gender.Ģż

āThere hasnāt been success in changing the cultural patterns that devalue women and consider them disposable,ā the report says. It defines femicide as the killing of women by their intimate partners.Ģż

Creating resources

Aside from headlines about missing or murdered women, the topic of machismo and femicide is rarely touched on in a systematic, educational way in Mexican society, observers say.Ģż

Thatās something the nonprofit Legalidad Por MĆ©xicoĢżhas noted as well. The organization was created two years ago by Teach for Mexico staff and alums, and it focuses on identifying challenges in Mexico that may not be directly related to the education system, but impact how students learn ā and whether they stay in school.ĢżLegalidad Por MĆ©xicoĢżfocuses on three broad themes: human rights, crime prevention, and violence prevention. They ask Teach for Mexico fellows to identify problems in their communities that are affecting their students, then train the fellowsĢżon how to create a course like the one GuzmĆ”n is conducting, offering resources on methodology and evaluation.Ģż

āThe hypothesis we had was that if you increase the knowledge of children regarding these three topics, give them tools to defend themselves from organizedĢżcrime, or violence, or understand their rights, they are going to be better able to increase their level of education,ā says Ćngeles Estrada GonzĆ”lez, managing director and co-founder ofĢżLegalidad Por MĆ©xico.

Ms. Estrada says she noted that there are problems that are unique to different regions of Mexico ā such as bullyingĢżor environmental degradation. But one issue seemed to have a universal presence in all of the communities where fellows work: gender discrimination.

āItās not just something we were hearing about in the north or the south. No, itās something all around Mexico,ā Estrada says.

Recognizing violence

GuzmĆ”n, who hopes to work for a gender-focused nongovernmental organization or womenās collective after finishing her Teach for Mexico commitment in July, says violence is normalized here. āAny kind of violence, itās all considered natural,ā she says. āItās ānormalā that an argument ends in death. Itās ānormalā for boys and girls in school to hit each other.ā

The first several weeks of her course focused on demystifying these ideas. She spoke to the students about the many different kinds of violence ā economic, physical, verbal ā and their basic human rights, like the right to keep studying, even if a boyfriend or parent pressures them to drop out of school.

āIn the street, [my classmates] really started to put this class into practice,ā explains Juan, the senior, saying they now call each other out if someone isĢżbeing disrespectful or violent in any way.

Abernece Valdez, a 17-year-old senior who has experienced catcalls walking to school, says sheās ālearned a tonā from the course. āI didnāt know that I have a right to education,ā she explains.

Sheās since started conversations in her home that she never could have imagined before. āMy dad is a little machista,ā she says. āHe wouldnāt let me wear shorts or skirts because he said it would provoke men.ā

With the vocabulary and tools she learned in GuzmĆ”nās course, she was able to sit down with her parents and talk about why she wanted to wear shorts: When itās hot outside, itās more comfortable for her. āItās not for men,ā she says. To her surprise, her father conceded.Ģż

But it also made her realize something important about her own behavior, she says.

āMy boyfriend would yell at me. He grabbed me. When we started the workshop I learned that wasnāt normal. Before, I thought it was just what happened, or that I provoked it,ā she says.

āI learned that thereās no point where itās OK to get violent.ā

She dumped him.

āAccess to information can create change,ā GuzmĆ”n says, hopeful that her work and her students will put a dent in machismo. The students are now tasked with teaching the same course to their family and community members.ĢżāThese lessons are reaching [beyond] my classroom.ā