Q&A: Educator Linda Nathan takes on systemic racism on campus

Loading...

Linda Nathan served as founding headmaster of Boston Arts Academy from 1998 to 2014. The reflects the racial makeup of the public schools throughout the city – about 8 out of 10 students are African-American or Latino. And more than half come from low-income families.��

Its graduation rate is higher than average – about 85 percent. And more than 90 percent of the graduates are accepted into college or career-training programs.��

But Dr. Nathan was disturbed to learn that only about two-thirds were finishing a degree or training program within six years. That rate is higher than the national average, but she wondered what needed to change to better support those who clearly had hit obstacles after school leaders like her had encouraged them to pursue their college dreams.��

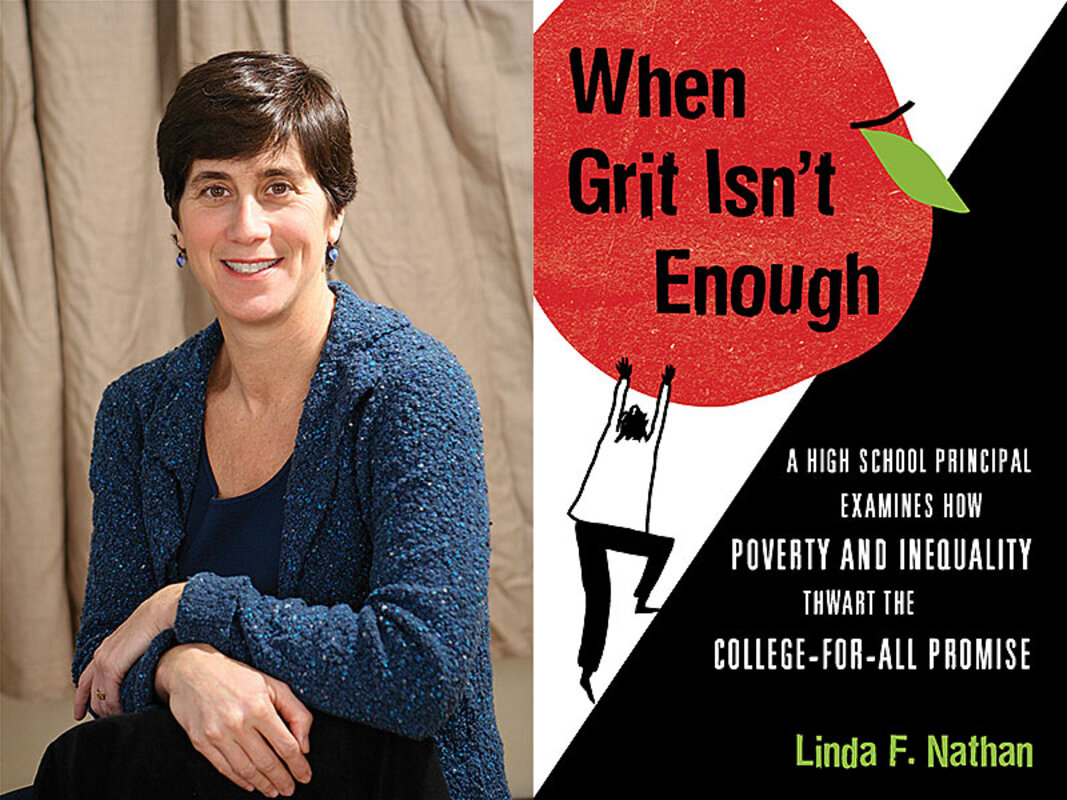

She interviewed BAA alumni about their experiences for her new book, “When Grit Isn’t Enough: A High School Principal Examines How Poverty and Inequality Thwart the College-For-All Promise,” published this week by Beacon Press.��

Nathan is now the executive director of the Center for Artistry and Scholarship, a nonprofit that fosters arts-immersed schools.��She spoke with the Monitor recently by phone about her new book. Below are excerpts from that conversation.��

Why did you title your book, “When Grit Isn’t Enough”? Is there an implication in some education circles that grit is a silver bullet?

Yes. [In many public schools with low-income students] there are emblems, flags about being “gritty” – all this “no excuses” stuff.

There’s nothing wrong with the word. But it’s promulgated by people who truly believe that if you just work harder you’ll be fine.

It’s true, you will��not��be fine if you��don’t��work hard. But working hard is not sufficient [for] kids who are starting behind the eight ball, who go to very under-resourced schools.

I saw some classroom practices in the no-excuses schools that just chilled me to the bone, that you’d never see in any middle-class school. It’s very rote, it’s very call and response, and I felt it was very punitive and oppressive.

I’m a huge proponent for the arts. If you think about the word “persistence,” which I like a lot better than “grit,” the arts is all about practicing and trying again and taking risks.��

You talked with many alumni of Boston Arts Academy about the role of race in their college experience. What surprised you about what they shared?

I didn’t expect the white kids to find the racial isolation as troubling, and��they really did. They really felt they had gone backwards once they got to college. And they were very articulate about how dangerous that is.

The kids of color, they were so used to being in the majority and now they were in the minority, and their stories were just chilling. But when I share those stories with other people of color, that’s all happened to them too, so I don’t know that it surprised me.

Why is it important for the systemic inequities students face to be brought into the foreground – and how can educational leaders do that better?

We have this notion of, just pull yourself up by your bootstraps and you’ll be fine. That’s really not true. We must understand what the most vulnerable of us are actually facing.

Colleges are absolutely not set up to support low-income and black and brown kids, and that’s what systemic racism is all about.

High schools have to figure out this partnership with colleges or employers, so that we can take collective responsibility for our kids.

What do you recommend that educators do differently to better prepare low-income or first-generation students who want to go to college?

I would get guidance [counselor] ratios down to 1 to 40 or 30, which is what suburban schools do.��

All kids need something like a senior project or a long-term internship. That’s how you get engaged in learning. All kids need a very comprehensive arts curriculum, because that’s where you’re going to learn to make and do, that’s where you’re going to learn to create beauty.��

Everybody’s got to have some kind of work experience. I would love to see a sort of a Peace Corps for all kids in this country, where everyone has to spend 6 months to a year doing some deep service work. That would really change the way we think about high school.

There’s no policy conversation right now about what it would take to have kids doing what’s called deep learning.

When kids are out in the world and not just in classrooms, they have an ability to integrate what they are learning from the work world to the classroom. It allows them to mature in very significant and positive ways.

Once low-income students succeed in high school and go on to college, why is money more of an obstacle than people often realize?

You’ve got your scholarship, and then your GPA dips down and you lose your scholarship. They miss a payment, they don’t have this or that, then they drop out. They’re done for life. There is no safety net.

I’m trying to say, stop blaming the kid. Let’s create some systemic responses.

What should high school and college educators do to address the racial undercurrents of society?

There has to be so much more work.

Maybe 10 years ago, there was a wonderful meeting [between] admissions people [from elite universities] and [Boston] high school headmasters and guidance counselors. It was one of the hardest conversations I’ve ever been at.

Those admissions people said things to us like, “We can’t take your kids if they’re not a fit, if they’re not good enough for us.” We said, “We think they are all good enough for you; we wouldn’t let them apply if they weren’t. But if you take them, you better support them when they get there.”

We need more of those conversations.

[Many] colleges don’t want to acknowledge that they’ve got a race problem. They’ll say, “We have this and that program.”��But you can’t “do racism”��on Tuesday and expect it to go away.

[A lot of] colleges don’t think they have a responsibility to teach race [or to get] kids to understand how to live in a pluralistic, multiracial society.

Our professional development hasn’t allowed for teachers to really talk about the difference between their own background and the kids they are teaching. [Many] teachers don’t have “race muscles”; they don’t know how to talk about race.

The push for all students to be prepared for college included a desire to end the kind of tracking that would give some students greater opportunities than others to prosper in the long term. How did you come to see that as fraught with false promises?

I’ve been in public education for 40 years and I believe deeply that we should have kids going on to college. But I also came to believe that we weren’t doing enough with career and technical education – that this notion that literally everyone would go to college, it doesn’t make sense.

As I began to visit more vocational schools and look at more of what was going on in Europe, I really became convinced that this country needs a paradigm shift.

Can high school re-embrace, without tracking, some very powerful types of career and technical training?

The population in our country that actually has work experience, it’s the wealthy kids, it’s not the low-income kids. That should raise incredible concern.

What are the potential equity concerns if high schools shift to more career training for students?

That’s what everyone’s worried about – [going] back to “voc ed,” where we housed the poor black and brown kids. If I’m a black or brown parent and you tell me my kid’s in the voc track, I’m saying, “No, ’cause my kid’s got to go to college.”

I want this to be for everybody. It’s a different approach. Until we can talk about [it] for all kids, we’ve got a problem.

We need to invest in community colleges; we need to invest in guidance counselors for our schools. We have decided as a society that we will invest in those that have and not those that don’t.

What’s your biggest reason for hope that things can move in the direction you’d like to see?

The kids [at my schools]. I’ve trained generations of kids. They will raise these questions. I even had a kid who’s run for City Council now. What gives me hope is that we’ll keep fighting.