Are electric cars really cheaper than gas cars?

Loading...

I’ve been looking through a developed by the US Department of Energy (DOE) to assist consumers in comparing the energy costs of driving an electric vehicle (EV), relative to posted gasoline prices in their state. I heard about this site at the US Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) in Washington, DC earlier this week. It sounded like a handy feature for both current EV owners and those considering buying one, but I couldn’t help thinking about it in the context of a presentation I saw at the same conference on the cost effectiveness of federal tax credits for EV purchases. A key question in both instances concerns just what kind of car is being replaced by that new EV.

The website uses simple math, together with the EIA’s continuously updated data on gasoline and electricity prices around the country, to come up with a national and state-by-state price for an “eGallon”. That imaginary construct is essentially the quantity of electricity that would take a typical EV as far as a gallon of gasoline would take the average new conventional car. As the text points out, it’s hard for consumers to do this for themselves. They see gasoline prices everywhere they drive but must dig through their utility bills to find their electricity price–not always obvious–and then might not know how to compare the two.

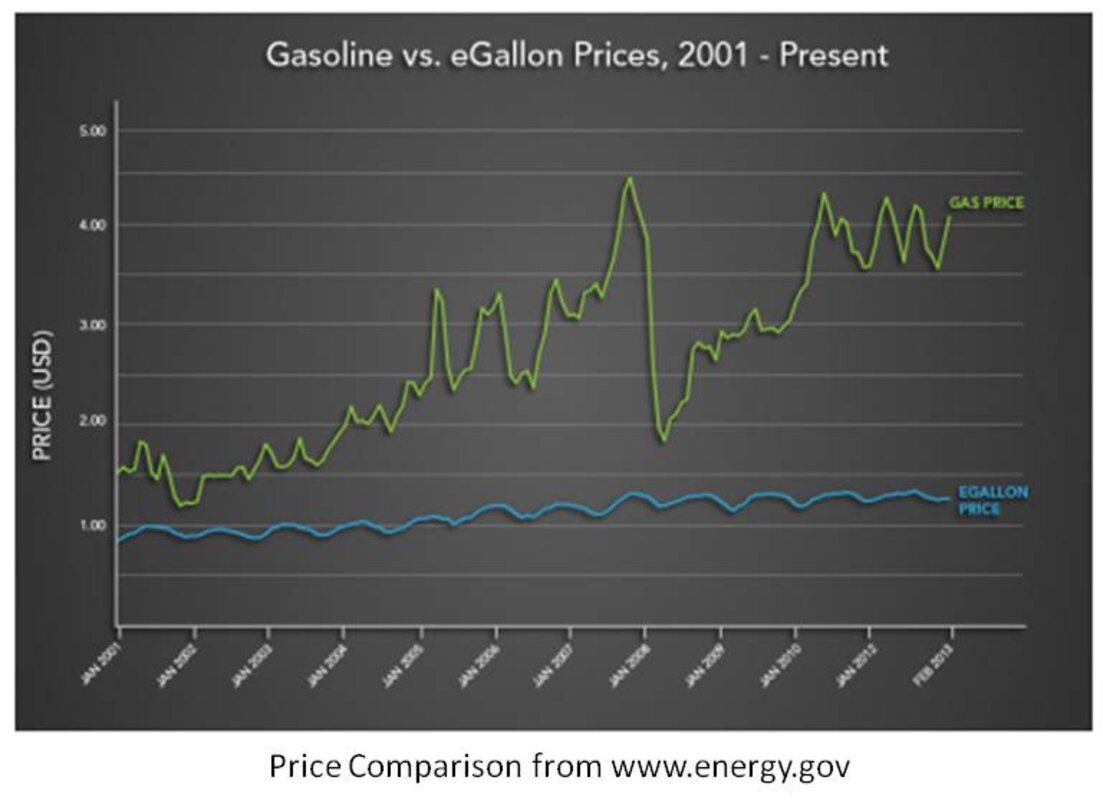

�ճ���� indicates the eGallon calculation is based on the average energy usage of five specific EVs, including the Chevrolet Volt, Nissan Leaf, and Ford Focus EV, along with the 2012 EPA fleet average fuel economy for what EPA defines as small and mid-size cars. The result is side-by-side postings of the US average gasoline and eGallon prices, plus a drop-down menu to replicate that for each state. The site also includes the chart at left, comparing these two prices over the last decade.

A Big Underlying Assumption

Two facts become immediately apparent. First, electricity is generally a cheaper fuel for cars than retail gasoline. That’s true for a variety of reasons, including the higher end-use efficiency of electric motors compared to internal combustion engines and the lower cost of most of the fuels used to generate electricity in the US. For example, the natural gas burned in power plants for the equivalent of $ 20.40 per barrel last year, while the global benchmark for oil averaged .

And just as there’s no single gasoline price for the whole country, neither is there a single electricity price. Even the state averages used by the DOE to calculate eGallon prices mask a bewildering variety of regional. So your cost to recharge an EV might not just vary by location, but by time of year, time of day, and the specific rate plan that applies to you. My main concern about the site derives from something much simper: the big central assumption that EVs compete with the average cars sold in America last year.

What Do We Know About Trade-Ins for EVs?

According to the eGallon site, the average small-to-medium US car in 2012 got (mpg) in combined city and highway driving. Using that figure, and with residential US electricity prices averaging (kWh) in March 2013, the national eGallon price for March would have been $1.14/gal., compared to for unleaded regular gasoline. But what if we assumed that the cars most often compared to a new EV were not average cars, but other efficient cars, as logic and my intuition suggest? If we substituted the for a conventional Ford Focus or Toyota Prius hybrid, the eGallon price would jump to $1.26 or $2.03, respectively.

In some respects this result is fairly obvious. If you were already contemplating buying a hybrid, an EV won’t save you as much as if you were thinking of buying a conventional mid-size sedan. However, this distinction is important enough that the DOE should consider refining its eGallon calculator. EVs are much like wind and solar installations that cost more than conventional alternatives, but are expected to produce over their lifetimes economic or environmental benefits that offset those higher costs. The attractiveness of that big up-front investment is directly proportional to those benefits.

I don’t have the data that would clarify the actual comparisons EV buyers are making, but someone must, perhaps including DOE. And it turns out that this isn’t just important for calculations like eGallon, but also for assessing the cost-effectiveness of federal EV policy.

EV Subsidies May Be Too Low But Are Already High for the Benefits They Create

That brings me to the Congressional Budget Office’s last fall. The report merits a posting of its own, but one nugget I gleaned from Monday’s presentation in DC was that the CBO found that the current federal credit of up to $7,500 per car was still insufficient to make most EVs cost-competitive on a full-life basis with conventional cars. Yet despite this, the effective cost to taxpayers of each gallon of gasoline saved by a Leaf-type EV was well over $6 when compared to conventional cars getting average fuel economy, but over $10 vs. high fuel-economy compact cars. That’s assuming they save any gas at all, because of the way the Corporate Average Fuel Economy rules have been structured Implied costs for greenhouse gas emissions avoidance were even more startling, at over $400/ton of CO2 in most cases.

Conclusion: To Be Valuable For Both Consumers and Taxpayers, DOE’s eGallon Must Reflect Realistic Vehicle Choices

The desirability of a tool like “eGallon” is rooted in the convoluted way we talk about transportation fuel economy and energy costs in this country. Miles per gallon itself is a poor metric, compared to something like gallons per 100 miles. It obscures the high value of modest improvements in high-consumption vehicles, while exaggerating the value of shifting from very efficient to ultra-efficient cars. It’s also more useful for policy makers than consumers, who are ultimately concerned about outcomes in dollars per mile or dollars per trip.

Recognizing the impracticality of training 300 million consumers to think about this subject differently, eGallon might prove useful, but only as long as it is grounded in the best information we have about the vehicle choices that potential EV buyers are actually considering. Since current EV incentives apparently provide a poor return to taxpayers, an overly simplistic tool that drives consumers too far in that direction might be worse than not having such a tool at all.