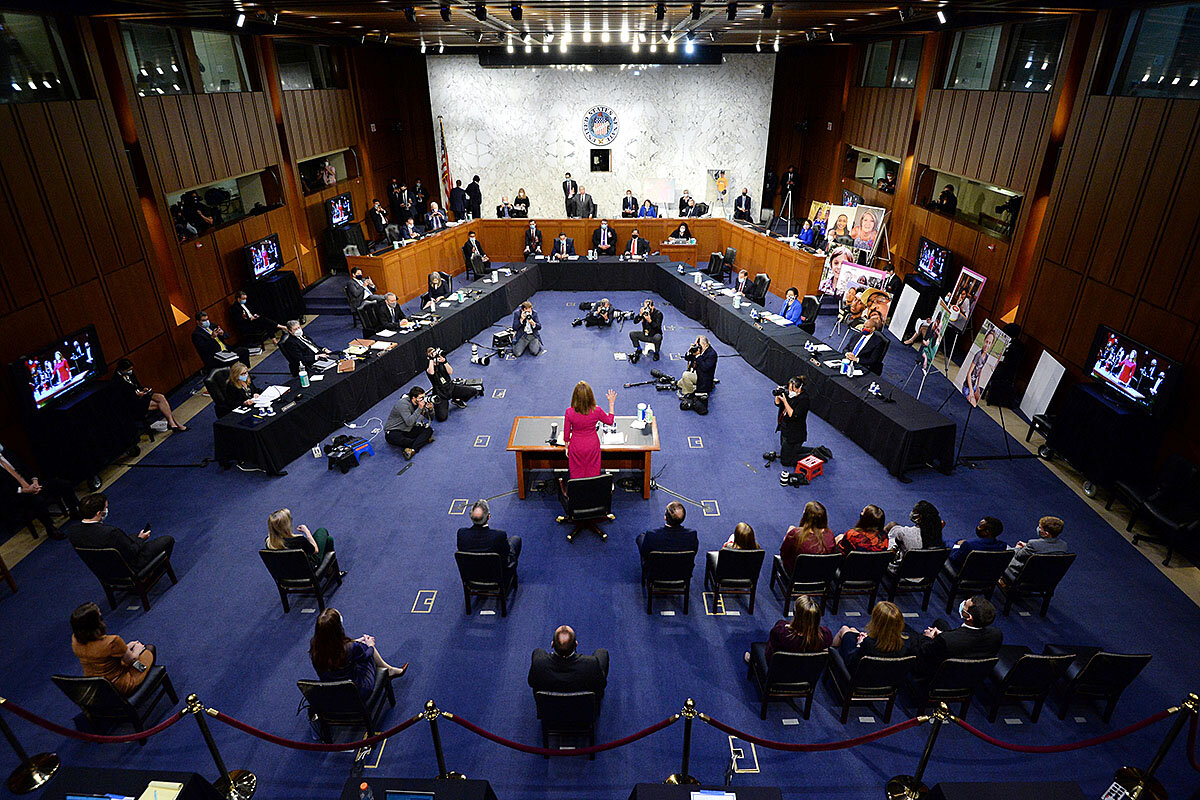

Who is Amy Coney Barrett? Senate hearings starting today will focus on the Supreme Court nominee's legal views. But other parts of her character have impressed even her opponents.

Why is ���Ǵ��� Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

About usAlready a subscriber? Log in

Already have a subscription? Activate it

Ready for constructive world news?

Join the Monitor community.

SubscribeMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

For many Nigerians, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad has long been synonymous with corruption, torture, and killing. The government force, created in 1992 to combat gang crime, has since become the symbol of Nigeria’s rampant problem of police violence. One study concluded that Nigerian police kill someone 58% of the time when they respond to a violent altercation, .

In recent days, protests have broken out across the country – the largest in years, . Protesters and journalists have been shot, with at least two deaths, and dozens remain in custody. But this past weekend brought a breakthrough, with the president vowing to disband SARS as “only the first step in our commitment to extensive police reforms.”

“This is an incredible accomplishment,” Bulama Bukarti, a human rights lawyer, told the Journal. And it has opened the way for deeper change. “SARS isn’t just an institution, but a mentality,” Mr. Bukarti adds. “This is only the beginning.”

For their part, protesters say they’re committed to that change. One : “We won’t stop, we’ll be here tomorrow and the next day and next year until there’s change.”

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 9 min. read )

Profile

( 10 min. read )

Jaime Harrison raised more money last quarter than any U.S. Senate candidate in history. This high-stakes election year is one reason. But he's also finding a place in the national conversation about race and polarization.

Patterns

( 4 min. read )

Have big Western democracies handled COVID-19 badly because they are democratic? No. It’s because they are no longer good at government. Asian democracies may offer lessons.

( 6 min. read )

Lawmakers worried about civil unrest are proposing an array of laws, such as protecting drivers who injure protesters in self-defense. Critics say the laws undermine “the right to assemble in America.”

Difference-maker

( 5 min. read )

The pandemic brought Doris Griffin out of retirement, and that’s a good thing for Texas’ seniors. When she found her purpose in helping seniors, she changed San Antonio.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

There are roughly 300 billion trees in the United States, according to the U.S. Forest Service. The breadth and intensity of wildfires this summer mainly across the Western states – 45,195 fires, 7,928,100 acres burned as of Oct. 8 – provide a stark measure of the increasing impact of climate change.

But there is another, more hopeful effect of climate change recorded in trees: a new vigor in civic engagement and concern for the well-being of communities, especially cities.

Take, for example, the Boston neighborhood of Roxbury. It is more densely inhabited than the Boston-area average. More than 90% of its residents are people of color. It is also one of the poorer and least vegetated areas of the city. More asphalt and fewer trees mean higher temperatures. When the city announced a plan to widen a main thoroughfare through the neighborhood, locals saw it as an act of environmental racism. The blueprints marked 124 mature red oaks and lindens for removal, to be replaced ultimately by 204 new trees. But saplings won’t provide shade for decades. Faced with sustained opposition, the city agreed last month to review and revise the plans – this time with resident input.

Similar discussions are taking place in cities across the U.S. as urban planners, residents, and activists strive to find a balance between population growth and conservation of the natural environment. As of 2018, according to Forest Service data, the total urban forest included 5.5 billion trees providing 127 million acres of leaf area. By 2060 that urban land will increase by nearly 100 million acres, the Forest Service says. Greening those spaces has measurable benefits. The current urban forest produces an estimated $18.3 billion in value through air pollution removal, carbon sequestration, and reduced energy use in buildings.

Trees also contribute to safer neighborhoods. Federal crime statistics show that public housing communities with greater amounts of vegetation and more open landscapes experience less than half the crimes of their less-planted counterparts.

“One of the things we have found is when we build community around trees, it gives [people] a voice. They’re a little less powerless,” Seattle environmentalist Jim Davis told U.S. News and World Report.

In cultures around the world, the relationship among trees, community, and individual spirituality is a common experience. On any given Sunday morning, countless church congregations gather beneath trees to worship in open urban fields across Africa. In Rwanda and Sierra Leone, community tribunals convened in the shade of trees to find reconciliation between victims and perpetrators of genocide and war crimes. Churches curate many of Ethiopia’s largest remaining mature forests.

As temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, arborists around the world are rethinking how forests will need to adapt. By the end of the century, for example, New England’s forests may need to look more like those currently in mid-Atlantic states. New York City biologists are already planting trees from Arizona. In Massachusetts, which has 60% forest coverage, 80% of that forest is privately owned. That gives town planners and backyard gardeners a primary role in preparing for a changing future.

“We are seeing landowners becoming more aware of climate change impacts and, more importantly, the role their land can play in mitigating climate change,” Paul Catanzaro, a forestry expert at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, told The Boston Globe.

Planting a tree has always been an act of selflessness, beauty, and optimism. As the climate changes, humanity is finding new seasons of living in balance.

A ���Ǵ��� Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

When we’re confused, anxious, or faced with a tough decision or task, turning to God for guidance lights our path. That’s what a public servant experienced firsthand when city contract negotiations initially hit a dead end.

A message of love

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at what the Supreme Court hearings say about how the Senate is changing.