It was the woman’s voice Jolyn Hopson heard on the news that Thursday back in July. A wail, a piercing pang of anguish, the kind only a mother could make, perhaps, during the first or last moments of a life.

My son! My son! He’s gone, because of some lowdown dirty dog!

Ms. Hopson first heard the voice in the morning. She had stayed home from work that day and was organizing her kitchen when a cry on TV made her body suddenly freeze. She took a breath and turned to watch. It was a crime report. The woman had lost her only son, shot to death the day before in their home.

Distraught, defiant, the woman was looking directly into the camera, addressing the young men she saw fleeing, before they were arrested by police.

I ran after you and I chased you. You did something to my son, who was innocent, so now you’re going to have to come after me. And may God get you!

“Wow. I saw her hurt. I saw her anger,” says Hopson, a budget analyst with the US Fish and Wildlife Service who lives in Arlington, Va. “And I was like, me? As a mother? You just naturally put yourself in that situation. How would I react? What would I do?”

The second of her two sons was the same age as the son of the woman on TV.

The woman’s voice stayed with her throughout the day, says Hopson. Then, about six hours later, a friend she was expecting to visit called. He couldn’t get to Hopson’s house, he said: The police had blocked her street.

Hopson went to look outside while still holding the phone to her ear. As she opened the door, she saw her home surrounded by an armed SWAT team. “Put your hands up! Put your hands up!” someone shouted.

“I couldn’t even understand the commands. I was in a state of shock,” she says. “I heard somebody say, ‘Ma’am, we don’t want to shoot you.’ ” Their weapons raised, police ordered her to walk slowly toward them. They handcuffed her and placed her in the back of a squad car.

They had a warrant to search the house, they told her. Her son was already in custody, soon to be charged with murder.

Hopson knew almost immediately.

It was the son of the woman she’d heard on TV.

***

It takes Giselle Mörch about an hour to drive from her home in Silver Spring, Md., to St. John Alpha and Omega Pentecostal Church in West Baltimore, one of the most violent neighborhoods in the United States.

The old stone church lies just a few blocks from where the sparks that kindled the riots of 2015 first erupted. The death of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black man who died of injuries suffered while in the custody of Baltimore police officers, still hangs heavy here.

Since then, the city has only experienced more violence: three straight years of 300-plus murders, including last year, which ended with the highest homicide rate in Baltimore history.

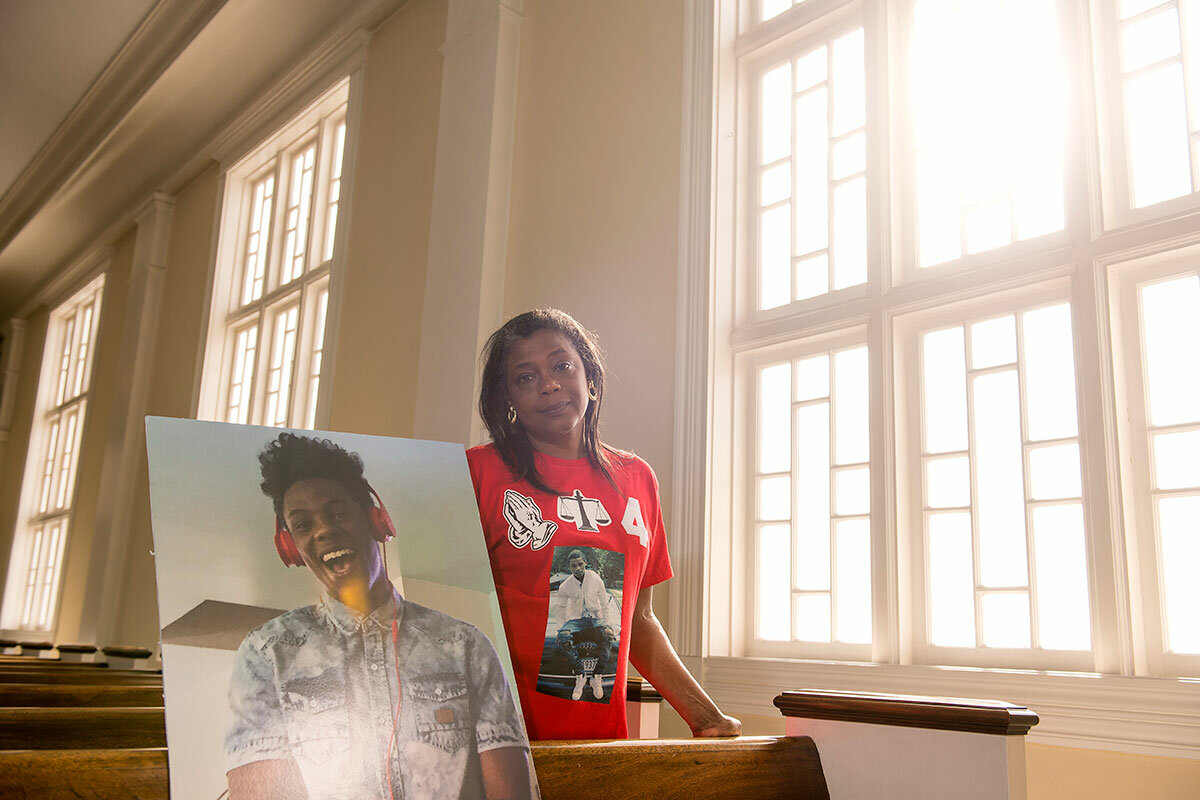

Yet, of all the places to seek solace and purpose, Ms. Mörch felt compelled to make the drive to West Baltimore. She hadn’t been interested in standard grief counseling or any of that after her son was killed last July, she says. How could anyone understand, really understand, what she was going through? Mörch, who has worked for the National Postal Mail Handlers Union for 20 years, was looking for the fellowship of mothers like her, she realized.

A friend had told her about an annual Mother’s Day event in Boston where families who have lost children to violence march to keep their memories alive. So she went online to search for something similar. Marveling at the coincidence, she noticed that a friend had “liked” a page on Facebook for an organization called Mothers of Murdered Sons and Daughters United (MOMS) in Baltimore.

The first meeting in the group’s office near the church was a beautiful experience, she says. The mothers shared an intimate bond, rooted in this singular and nearly indescribable malaise of grief.

“We have the same emotions,” she says of the mothers she met. “We’re looking for the same things. We’re looking for justice, and we want our sons and daughters remembered.”

She shared her story and listened to those of other mothers. She wept with them. She talked about ways to preserve her son’s memory.

But creating a space for these intimate bonds, as she soon discovered, was not the only mission of this community of MOMS. The group is also an active part of a wide-ranging and interconnected network of grass-roots organizations. They work on crime prevention and anti-recidivism issues, they work with social services and other victim advocacy groups, and they work closely with the Baltimore Police Department. They’re also connected to political advocacy organizations, especially those battling easy access to guns.

But the primary focus of MOMS at these early meetings was something that disturbed Mörch, even though it had always been at the center of her own ���Ǵ��� faith: the power of forgiveness.

“Without forgiveness, there cannot be healing,” says Daphne Alston, president and founder of MOMS. “I think it’s important that we move forward together, because the only way we’re going to heal, the only way we’re going to reconcile, [is by bringing] everybody together – the murderers, the perpetrators, the victims, the community. This is how we’re going to heal.”

Forgiveness. Mörch realized how much the concept had always been an abstraction for her, never something so painful and radical. Forgive as you have been forgiven. It’s a religious catechism. A duty, even. But now, confronted with the call to forgive in a way she could never have imagined, it has become something more wrenching and tumultuous, she says.

Police say two suspects entered her home in Silver Spring last July to see her 20-year-old son, Jaycee. She was there, along with other family members. The authorities say a marijuana sale turned deadly. Shots were fired, striking and killing her son.

Though she cannot discuss the case now, Mörch told TV reporters that day how she chased the suspects out of the house. She saw one scramble into a car, where another young man was waiting to drive away. Later that evening, as she met with her son’s friends at a candlelight vigil covered by local news, she mourned. My son! My son!

“If you’re a parent, you’re always in protective mode,” she says of that moment. “You protect your loved ones, and when this happens, you are crushed. This happened on my watch? No! You are supposed to be the protector. And that’s how I’m still feeling.”

“My son wasn’t out in the streets,” she says. “He was in the protection of the sanctuary. Your residence is your sanctuary, and when that is violated, when that is violated, where can you feel safe then? Where? If you can’t feel safe and protected in your own residence, where can you?”

No. She wasn’t sure she could really find it in her to forgive those who killed her son. Not now. Maybe not ever.

***

Hopson knew she needed help soon.

She’d lost more than 50 pounds after her son was arrested. She’d taken time off work to stay with her family in South Carolina, not knowing what else to do. She wrote a prayer for strength, and woke up every morning at 6 to recite it and perhaps find a way to heal.

Her family was worried. “Baby, you’re in so much pain,” she recalls her aunt telling her. “I know,” Hopson replied. “I know my boy is incarcerated, but there’s a woman that lost her child, and I’m having a hard time dealing with that.”

Her sister had a suggestion. “You know what, Jo? You already have that prayer you wrote down. Why don’t you write another prayer for their family? Read your prayer, and then read the prayer [for them].” Hopson did, making it part of her morning routine.

After she returned from South Carolina, she traveled to New York to stay with other family members. She still felt a quiet desperation.

Throughout her career, she had been exposed to many different aspects of criminal and social behavior, and certainly had seen people at their best and worst. She had served for 10 years in the military, including as a military police officer, a corrections officer at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, and a criminal investigator at Fort Myer in Virginia. She later worked as a parole officer in Washington, D.C., before getting a Master of Business Administration through a veterans program that led to the job with the Fish and Wildlife Service.

But none of it, nothing, had prepared her for the piercing experience of having her own son in jail, accused of murder.

So she decided to look for groups of mothers who might be going through similar turmoil in their lives. She actually found an organization called Mothers of Incarcerated Sons Society. But she also came across a group called MOMS. She decided to click on one of its videos.

She saw Ms. Alston, the founder, talking about the organization’s yearly theme of forgiveness. But then some of the mothers spoke on the video, expressing their pain and the rage they were still feeling toward those who murdered their children.

“Oh, this is not for me,” Hopson recalls thinking.

Then another woman shared some thoughts on the video. It was Mörch, the woman she’d been praying for.

***

When the judge presiding over the case walked into the courtroom last December, Mörch and Hopson were sitting on the traditional opposite sides of the court. Everyone rose.

The judge turned to talk for a few seconds to one of the guards. Then, looking out over the courtroom, Hopson recalls him quipping: “There’s too many people standing in this courtroom.”

“Well, you never told us to sit,” joked back Hopson’s older son, Eric, not quite under his breath. Guffaws rippled through the courtroom, and Hopson nervously looked around the room.

Her eyes met Mörch’s. The mother of the dead man wasn’t quite smiling, but Hopson thought she saw a twinkle of mirth.

Hopson cupped her hands over her heart, and mouthed the words, “I’m so sorry.” Mörch looked confused; she couldn’t understand. Hopson repeated the gesture and mouthed the words again. Mörch waved to her to come out into the hall, and they found an empty room.

“I always wanted to tell you this, but I’m so sorry for your loss. I really am,” Hopson recalls saying, telling Mörch that she was the mother of one of the accused, the young man Re’quan, who police say was driving the getaway car. (All three have been charged with murder.) “And I wanted you to know that I’ve been praying for you and your family.”

Mörch was stunned. Both began to weep. They embraced.

“My immediate reaction to her was just being in pain,” recalls Mörch. “We’re mothers, and we’re mothers in pain. It was just one mother to another mother. We both lost our sons. The only difference is, her son is still alive.” (He has also not been convicted of the crime, for which he will stand trial this summer.)

They went back into the courtroom and returned to their seats on opposite sides. But Mörch says her mind was racing after the experience. Almost immediately she began to feel waves of conflicting emotions.

“At first, you know, there was a struggle in me about the praying part,” she recalls. “First it was like, well, I thank you for praying for me. But then it was like, well, this is what your son did to my son. What right do you have to pray? And then I went back, well, God wants us to forgive so we can heal.”

She couldn’t shake her ambivalence about the call to forgive. “You don’t want to hear the words, ‘Oh, I’m sorry.’ Because the word ‘sorry’ is just thrown out there to cover stuff,” Mörch says. “Are you really sorry? Or are you saying sorry because you’re caught, and by saying sorry, that might lessen your guilt, or lessen what punishment happens to you?”

But after the court hearing, she decided to wait for Hopson outside. She gave her a handwritten invitation with an address in Baltimore. She was part of a group of mothers that was going to have a “forgiveness banquet” on the following evening. Would she attend?

Hopson said she would try, but she knew she probably couldn’t. She was planning to visit her son, who was being held in the county jail, that day.

“My son is incarcerated, and I’m his mother, and I’m going to be there every step of the way,” she says of her thinking at the time.

***

Hopson didn’t make it to the banquet, but Mörch was there, and what she heard that night was deeply personal in ways she wasn’t expecting.

The featured speaker was Darryl Green, who described a moment in which a person upended his family’s life forever, a moment that Mörch, too, now knows all too well. In 1988, a 14-year-old named Kinyom Marshall stabbed to death Mr. Green’s younger brother in a dispute over sneakers. Green, who had a master’s degree in criminal justice and wanted to become an FBI agent at the time, nearly spiraled out of control.

“I was angry for a long time,” says Green. “I didn’t run from trouble, I ran to it.... And I was so angry, angry every minute of the day. I would just pray and say, ‘Get this off me somehow, and give me something else.’ ”

Over time, he decided not to pursue a career in criminal justice but to work in social services instead. By 2012, Green had already been thinking about “deep forgiveness,” a mental state that he believes can require a lifetime to achieve but is essential for healing.

Along with his father, he made a conscious decision to forgive Mr. Marshall and then testify in court in support of his release. Marshall was serving a life sentence without parole, but in part because of Green’s and his father’s testimonies, the judge resentenced Marshall to a 30-year term, which made him eligible for parole.

“In the courtroom, [Green] was there, and his family was there, before I even knew that I was coming home,” Marshall says. “They spoke up for me.”

“For him to say that he forgives me? I mean, this is something big,” says Marshall, who now works as a forklift driver in Baltimore. “You’re talking about a life. You’re not talking about something of material value that can be replaced. You’re not talking about money. You’re talking about life.”

Green has since started an organization called Deep Forgiveness that promotes

reconciliation and healing, and Marshall often appears at talks with him. Green admits that it is still not easy to work closely with his brother’s killer at times.

“I’m only human,” he says. “Not every day is a good day. I think about the fact that, hey, my brother will never get to meet his nieces. He’ll never get the chance to get married and be a father. And all those other things you think about that bring you to a not-so-good place.”

Marshall wasn’t present at the MOMS banquet, but Green recounted their story and talked in his own street-hardened way about a subject that academics call “restorative justice”: ground-level efforts by communities to mend the deep ruptures that crime and violence can cause. Restorative justice is less about the power of the state and the criminal justice system than about individuals seeking to restore their lives together.

“How many of you feel like you are dying inside?” Green recalls asking the group. “How many of you are carrying this huge weight around?”

“Forgiveness is not about the other person,” says Green, who has sought to address Baltimore’s crime problems by working mostly with men released from prison or those struggling with homelessness or substance abuse. “It’s about having difficult conversations and just telling our stories and being willing to listen. Sometimes it is a spirit of unforgiveness that will kill you.”

Mörch listened intently that night. “Wow, just by how he involved the man who murdered his own brother in his own forgiveness journey? That was amazing,” she says. “For me, OK, you killed my brother? You killed my son? To me, I don’t want nothing to do with you. To me, you don’t exist.”

Afterward she recalls asking Green how long it took him to reach that point of forgiveness.

“It doesn’t happen overnight,” Green recalls responding. “It took me about two decades to reach that. You get to a point of being OK, and then I would go backwards. But hurt people hurt people. On your journey to healing, you may not even get to forgiveness, but you don’t have to put any parameters around how long it’s supposed to take.”

***

Alston, the founder of MOMS, began January’s monthly meeting at the Pentecostal church by acknowledging that many members were still struggling with last year’s theme.

“Towards the end of last year our focus was on forgiveness,” said Alston, whose son was killed in 2008, a homicide that still hasn’t been solved. “It’s not been going well with a lot of people, because there’s been so much trauma in the city, so much homicide. People are not ready to forgive the person who has killed their child.”

She invited people to speak, noting there was a lot to get through that evening. Groups such as Moms Demand Action and Marylanders to Prevent Gun Violence were updating the mothers on gun control efforts coming up in the state legislature.

Two advocates with the Baltimore Police Department, James Dixon and Falema Graham, were also there. The department hired both of them within the past year as part of a new program to help the families of victims navigate the impersonal and harsh edges of the criminal justice system.

A man named Nathaniel Powell wanted to address the mothers, too. When he was 17, he shot a Baltimore police officer and served 21 years in prison. Now 39 and released just a few months ago, he’s making a documentary to show young men the consequences of criminal behavior, including the lifelong effects on victims.

“I’m sitting here, fighting back tears listening to y’all,” he says later. “I’m feeling emotional because I really haven’t done nothin’ to be able to deserve this.”

But as she always does, Alston first asked whether any of the mothers would like to share any thoughts. Alice Oaks stood up.

“I lost both of my sons to murder, my only two children,” she told the group of around 35 people gathered in the church’s smaller sanctuary. “We spoke about forgiveness – I lost my first son in 2008. I prayed to God to put forgiveness in my heart for the person who killed my son, and I don’t want that person to have a strong hold on me. So I forgave him.”

“But in March I have to go to court, go through the trauma all over again,” Ms. Oaks said of the fatal shooting of her second son, in 2015. “Another double whammy. So I’m like a fickle person right now. I forgave him, and I still forgive him, and I still ... but this second murder – I just keep praying to God to keep strengthening me to press forward.”

A woman unfamiliar to the members rose. She introduced herself as Jolyn Hopson. “My son has not been murdered. He’s incarcerated,” she told the group. “He’s incarcerated for an incident with Miss Giselle’s son.”

The room fell silent. Mörch was sitting at a table, looking down, a few feet away.

Hopson told the story of her malaise, how she was looking for help, and how she found MOMS. “I saw Miss Daphne speak about forgiveness, and how we can’t point fingers, but in order to solve this we all have to come together.” She looked over. “So thank you, Miss Giselle, for the forgiveness.”

“Immediately after I first saw Miss Giselle, and I saw her pain, and her hurt – and we’re in a legal issue, of course – so when I was in court, and I looked at her, I had to tell her that my heart hurt,” she said to the mothers.

Sitting at the table, still looking down, Mörch began to sob quietly.

The room was transfixed. Mörch stood and she and Hopson, for a second time, embraced. Others in the room began to weep.

“I’m the mother of a murdered daughter,” one woman said. “This is a meeting I’ve never seen before. This isn’t easy. I call you courage, miss,” she added, looking over at Hopson.

“This is so big for me,” said Alston. “Because every time I say, ‘I quit. I’m not doing this,’ God keeps blowing my mind. He answers our prayers, and that means He has an answer for homicide as well. We’re on our way to making a big change. This is what helps bring all of us together.”

***

For Mörch, however, the moment was more complex. “That was a learning experience – that was an awesome experience,” she says later, adding that it was even “mind-blowing.” “But I had mixed emotions. I’m not going to lie.”

“I was kind of shocked that she was there, and part of me was just annoyed that she was there,” she continues. “It was like, well, the reason why I’m here is because of what your son did. I invited you to the forgiveness banquet, but I didn’t know you were going to come to the community meeting.” It even crossed her mind that Hopson might want to pick up information and use it in the trial. “This may be me being selfish, but it’s a form of, you’re not really part of the community.”

Hopson says one reason she came was simply to pay Mörch her respects after missing the banquet. “I didn’t want her to think I just blew her off after the moment we shared in court,” she says.

Hopson called the director of MOMS afterward, expressing her eagerness to contribute, perhaps organizing a memorial basketball tournament, with jerseys emblazoned with the names of murder victims.

In the end, however, most of the MOMS members thought it would be better if she did not return.

“I didn’t even realize that wall, that boundary, was up,” Hopson says. “But I see the hurt behind it, the pain. So I would never sit back and judge the situation.”

Still, Hopson feels she was led to MOMS in a way she couldn’t quite understand. The voice of Mörch seemed to just burst into her life, she says.

“Was it God’s will that I be there? I don’t know,” she says. Oaks, the woman who lost both of her sons to violence, reached out and offered to help Hopson find another group where she could try to heal. And a number of people came up to her afterward, saying they admired her courage.

For Mörch and others, Hopson’s presence would have disrupted the intimate bonds they’d formed through their shared experiences. Besides, the trial of the three men accused of Mörch’s son’s fatal shooting is set to start soon, and they remain on opposite sides in the retributive side of justice.

“I will say that I respect her, and I’m hoping that she and I can work together and we can do something for the youth,” Mörch says. “I don’t mind getting together with her, get tea, sit down and talk – I don’t mind. She did not do anything to me. It was her son.”

But the experience has impressed upon her the difficult journey toward both forgiveness and justice. And truth be told, she’s hoping more for retribution rather than restoration for the death of her son.

“For me to forgive the one person, yes it’s hard, it’s a struggle, but that’s nothing,” Mörch says of her encounters with Hopson. “I mean, if I forgave all of [those charged with the shooting], then that’s a big wow. Wow, they’re all forgiven.”

“Right now I’ve only made a baby step to forgive once,” she says. “I’ve not made the big steps to forgive the others. You know, I still want justice for my son, and whether I get it here on this earth or I don’t, I will have to live with that, and so will they, as God is the final judge.”