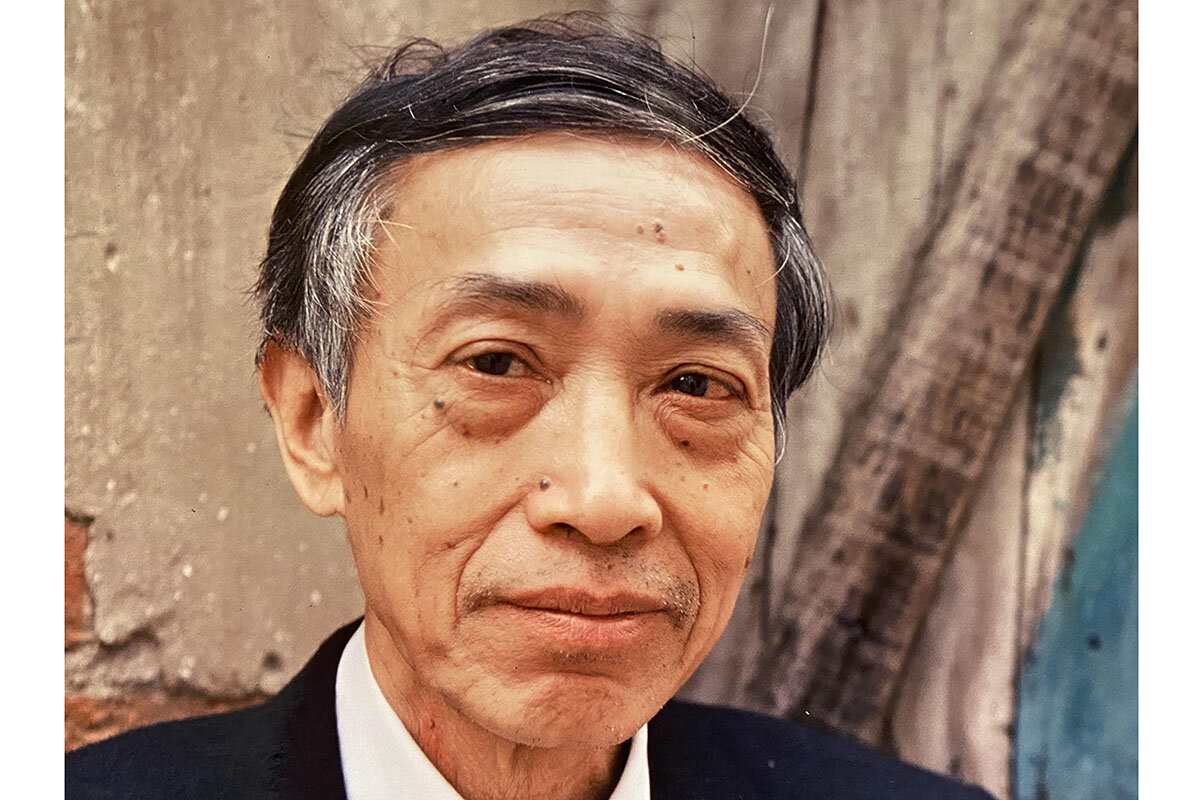

Bridging worlds with words: Vietnamese poet, translator Duong Tuong

Loading...

| New York

It was 1998 in New York. I was planning my exhibit, “Layers Through the Mist, Vietnam Images,” held at what’s now known as the Penn Museum. Earlier that year, I had met translator and poet Duong Tuong in Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, and now he was here, visiting the city with a group of his artist friends. I was invited to have dinner with him.

While eating at Nha Trang on Baxter Street, I told him about the exhibition. At that moment, he began to write one of his poems, “At the Vietnam Wall,” on a paper napkin. When I read those poignant words, I knew I wanted the poem to be included in my exhibit. He agreed.

How I wish I had saved that napkin.

Why We Wrote This

The determination and generosity of Vietnamese poet and translator Duong Tuong still resonate with this American photographer, bridging their different worlds.

Initially, I photographed in Vietnam in 1993, uncertain how the people would react to me, an American. After all, I represented a former enemy. Their openness surprised me. During my many later trips to the country, I spent time photographing in rural areas. There, walking in the muddy soil of the rice fields and being invited into the homes of strangers to share tea, I came to understand the determination, discipline, and generosity of the Vietnamese people.

I first met Duong Tuong at his Hanoi home, which was also an art gallery managed by his daughter, Tran Phuong Mai. Opened in 1993, it was one of Hanoi’s first private art galleries, or, more accurately, a salon, where writers, artists, and intellectuals gathered for hours over tea or coffee, discussing life and critiquing each other’s work.

The building was a two-story, 1930s French villa with a courtyard. On the walls hung works by well-established masters along with pieces by the Gang of Five, five painters considered pioneers of Vietnamese contemporary art – Tuong supported their ideas and works. There were poetry readings and music performances as well. And drifting throughout were the smell of incense and the sound of vendors outside, shouting their offerings.

Foreign influences lingered, beyond the architecture. You could literally taste French colonial rule. I found great French bread everywhere, and I had the most delicious Napoleon pastry in a tiny Hanoi restaurant, where the owner wore a French beret, and a huge photo of himself with Catherine Deneuve, star of “Indochine,” hung on the wall.

Tuong had fought the French, joining the resistance and fighting against them for years. But their presence in the country had an ironic twist. Tuong taught himself French and English, and read books found in captured French outposts.

For decades after his army time ended in 1955, he wrote poetry, reported and edited for the Vietnam News Agency, and, to make ends meet, became a translator.

Tuong’s work introduced Vietnamese readers to Western literature of all types, from “Gone with the Wind” to works by Proust, Chekhov, Camus, and Tolstoy, among others. Given his background, this was an incredible feat.

When working on my book, “A World of Decent Dreams, Vietnam Images,” I realized how many Vietnamese people had read “Gone with the Wind.” Relating the novel to Vietnamese culture and values, one woman said that Rhett Butler would return to Scarlett because she cared so much about her family and their land. From this woman’s perspective, Rhett would have given a damn.

I admired not only Tuong’s intellect, kindness, and sensitivity, but also his determination, as he neared 90, to translate the 19th-century poet Nguyen Du’s narrative poem “The Tale of Kieu,” considered a masterpiece of Vietnamese literature. Tuong had thought of tackling it many times. Now he was ready. Barely able to see, he needed readers to assist him, but having learned much of it by heart, he also translated from memory. It was published as “Kieu: In Duong Tuong’s Version” in 2020, just a few years before his death earlier this year.

Poetry was always Tuong’s chosen vehicle to express himself. He constantly slept with words that inspired him and kept him up at night.

His words I treasure most are those he scrawled on that wrinkled napkin. Transferred to a large board, they hung next to my images where museum visitors could reflect on his thoughts.

At the Vietnam Wall

By Duong Tuong

because i never knew you

nor did you me

i come

because you left behind mother, father

and betrothed

and i wife and children

i come

because love is stronger than enmity

and can bridge oceans

i come

because you never return and i do

i come

Nearly 25 years later, that poem remains relevant to our troubled times. The beauty of these sleepless words still inspires me: “because love is stronger than enmity.”

For decades, has captured images around the world with a focus on Asia and Africa, recording people and places before what is unique to them is lost.