Amid immigration enforcement, migrant farmworkers’ numbers are falling

Loading...

​In the Trump administration’s push to detain and deport unauthorized immigrants, some of the most highly publicized raids ​have occurred at farms ​or meatpacking operations in major agricultural states such as California, Washington, and Nebraska. More than 4 in 10 of America’s crop farmworkers lack work authorization, according to the Department of Agriculture.

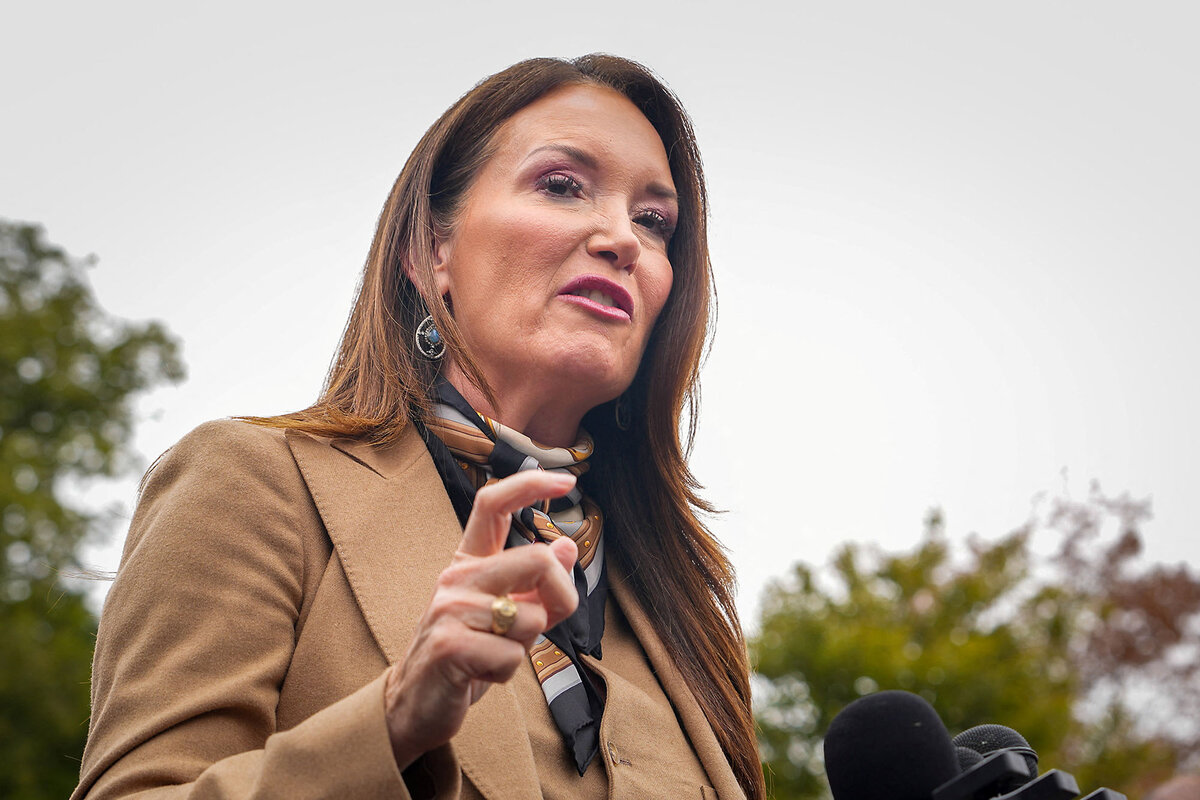

But the administration has sent mixed signals about the extent to which its immigration enforcement raids will target farmworkers, as opposed to unauthorized immigrants working in other sectors of the economy. On the social media platform X, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins she backed “deportations of EVERY illegal alien.” In the same post, she wrote, “Severe disruptions to our food supply would harm Americans,” adding that the administration is, nonetheless, “prioritizing deportations” of those they believe are unauthorized immigrants.

The number of farm workers has already dropped significantly: Economists Robert Lynch, Michael Ettlinger, and Emma Sifre, from the independent firm Economic Insights and Research Consulting, ¬Ý"agricultural production is heavily dependent on unauthorized labor," and that¬Ýbetween March and July, the number of farm laborers decreased by 155,000, or 6.5%. It‚Äôs unclear how many farmworkers are among the 59,762 people in immigration detention as of Sept. 21, according to Immigration and Customs Enforcement figures analyzed by . Still, immigration arrests are having profound effects on the livelihoods of countless migrant families across the country. The arrests could also impact the prices of fruits, vegetables, and meat that Americans purchase in grocery stores.

Why We Wrote This

U.S. immigration enforcement isn’t focused on the agriculture industry. But some businesses have been hit, and the farm labor workforce is shrinking. One result is expected to be rising grocery prices.

For now, there are still enough laborers in the United States willing to take the risk of coming to work, says Philip Martin, professor emeritus of agricultural and resource economics at the University of California, Davis.

“What we have seen is that when ICE conducts a raid on a farm, the next day, nobody shows up to work,’’ Professor Martin adds. “But in a short time, everyone comes back. People are poor, and they have to come to work. If you’re going to have an effect, it’s going to have to be a sustained effort, and people get scared, and some people go home.”

The uncertainty is impacting both employers¬Ý‚Äì who might need to find workers to replace those who were deported or fail to show up for work¬Ý‚Äì and the U.S. economy, as some economists argue that the results of immigration enforcement are driving up prices.

Professor Lynch, Professor Ettlinger and Ms. Sifre wrote that “there are early signs that the labor shortages are starting to reduce production and boost food prices.” Earlier this month, the Department of Labor issued a warning in the Federal Register that the immigration crackdown on unauthorized workers could threaten "the stability of domestic food production and prices for U.S. consumers."

Recent raids

A spate of raids in states across the U.S. has food producers scrambling, even if they are abiding by immigration rules or guidance for immigrant employees.

At Glenn Valley Foods in Omaha, Nebraska, owner Gary Rohwer says he began using an employment-authorization system called E-Verify several years ago to vet workers, at the recommendation of the Department of Homeland Security and the Agriculture Department. The system, which several states for employers, has been criticized for failing to detect .

This past June, ICE arrested 76 workers – half of Mr. Rohwer’s workforce – at his Omaha plant.

“On one hand, I was mad as hell,” says Mr. Rohwer. “And on the other hand, I was next to literally crying. I mean crying tears out of my eyes, to see these young Hispanic mothers, with little kids, in handcuffs.”

After the raid, he says he held a frustrating meeting at his conference table that included members of Homeland Security.

“Where do I go from here?” he recalls asking. “And the answer to that question was: You continue to E-Verify.”

His company has hustled to rehire. But since the June 10 arrests, Mr. Rohwer says his operation hasn’t fully returned to normal.

‚ÄúThis could have been my demise,‚Äù he says.¬Ý‚ÄúNobody seems to come up with a solution. If all these people were legal, there probably wouldn‚Äôt be any raids.

“The Americans, they don’t perform,” he adds. “We need the Hispanics. And Trump is saying they’re taking jobs. They’re not taking our jobs. There’s no way they’re taking them away. Because the Americans don’t want those jobs.”

While reports across the country suggest that some unauthorized workers are staying home from their jobs, due to fear of arrest, many appear to continue working out of necessity.

Immigrant farmworkers are a “very poor workforce” despite their “essential role in our food system,” says Antonio De Loera-Brust, a spokesperson for United Farm Workers, a labor union with roughly 10,000 members with varying immigration statuses. “This is not a workforce that can afford to stay home for weeks, let alone for years on end.”

The number of unauthorized-worker arrests on farms and food-production sites so far is unclear. Responding to an inquiry about those arrests, an ICE spokesperson said the agency didn’t have local statistics to share but suggested that the Monitor file a Freedom of Information Act request. Customs and Border Protection, which includes the Border Patrol, referred the Monitor to ICE.

Farm labor visas

Part of the immigration debate centers on the visa designed explicitly for seasonal migrant laborers in farms and ranches. The visa helps farmers fill temporary employment gaps by hiring foreign nationals to plant crops, cultivate, and harvest, as well as perform other agricultural tasks.

The number of approved H-2A visas has about eightfold in the past two decades, from 48,000 in 2005 to around 385,000 in 2024.

Farmers say the H-2A program helps them stay in business, as young people leave rural areas to seek employment in urban areas. Immigrant advocates, meanwhile, raise concerns about worker protections; the visa has at times been linked to .

In apple country – which includes states such as Washington, New York, Michigan, and Pennsylvania – 2025 is to be a banner year. The Agriculture Department predicts that overall apple production will increase by 1.3% to more than 275 million bushels. But labor shortages are taking a toll on farmer profits.

Lynsee Gibbons, the director of communications for the industry advocacy group USApple, said that the minimum compensation rate for H-2A labor has increased over the past five years – up 30% to an average of $17.74 per hour – and has become a growing burden for farmers.

“Apple growers would prefer to hire domestic workers whenever possible,” Ms. Gibbons says, but she adds that fewer and fewer Americans are turning up to do the job. “With this trend unlikely to change anytime soon, the U.S. apple industry must have a well-functioning, affordable alternative.”

Professor Martin, from UC Davis, believes that farmers are unlikely to rely on U.S. labor to fill in their gaps. Instead, he wrote in a recent blog post for Rural Migration News, removing the estimated 850,000 unauthorized farm workers over the next 10 years would speed up a long-term trend toward mechanized agriculture, expand the legal H-2A program for authorized migrant workers, and increase food imports from abroad.

Dwight Baugher, who runs Baugher’s Orchards and Farms in Westminster, Maryland, says he mainly hires his laborers from Mexico through the H-2A program. In his opinion, Americans generally aren’t willing to do the work that his crews do.

“It’s hard work, it’s hot, it’s dusty,” says Mr. Baugher. “My guys, they’re old-school workers, and they work at $18 an hour. The general American public, I can say I’d pay them $50 an hour, but it doesn’t matter what I pay them, they’re not coming back after lunch break.”

What are your questions about the U.S. immigration system that you would like to better understand?¬ÝReach out at¬Ýimmigration@csmonitor.com, and the Monitor may follow up to learn more. Your name and response will not be published without your permission. Your responses may shape the stories we report and how we report them.