Trade turns chilly: Chip embargo symbolizes deeper US-China strains

Loading...

In the heady days after the fall of the Soviet Union, globalized trade became an article of faith. The more trade, the better. It not only made nations richer – it also made them less willing to go to war because the economic costs of doing so kept going up.

Over the next three decades, however, doubts began to creep in about this globalization. Some nations made out better than others in a win-win world. Others – such as Iran and North Korea – kept up their militaristic ways, even when sanctions imposed economic costs on their actions.

Now, many nations are asking the opposite question: Could they be vulnerable from too much trade, especially with countries that don’t share their values or strategic aims?

Why We Wrote This

Is global trade in Cold War 2.0? Whatever you call it, how far China and the West drift apart may depend on finding a new equilibrium between national security concerns and a desire for growth.

This reconsideration of globalization is happening bit by bit, nation by nation, and even company by company. It’s most clearly seen in the gradual drifting apart of China and the West, particularly the United States. And there are no easy answers because, even as trade ties fray, the benefits of globalization remain strong. Trade continues to fatten consumer pocketbooks, boost corporate profits, and bring down prices on thousands of goods from toys to solar panels.

“This tectonic shift is moving very slowly, but notably,” says Joerg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China and longtime Beijing resident. “What keeps us together are the consumers.”

Analysts struggle to define this new period with a name: decoupling, deglobalization, Cold War 2.0. This new era has elements of all of these, but it really represents a lessening of faith that economic ties can build common ground among nations despite their geopolitical differences. How far China and the West drift apart may depend on where concerns about national security and desire for economic growth reach a new equilibrium.

The rethink of globalization stems from a range of events. After Russia’s Ukraine invasion last year, Europe’s overreliance on Russian natural gas became obvious for all to see. During the pandemic, the U.S. fretted it was too reliant on China for face masks and other personal protective equipment – adding to a wider rise in U.S. national security concerns about trade with China in recent years. Now, nations and companies alike are reevaluating their supply chains to see if they’re jeopardizing their own security by importing too much from a single source or exporting too much of their cutting-edge technology.

A digital “oil embargo”?

Perhaps the clearest bellwether for this new era involves semiconductors, the computer chips embedded in everyday items from alarm clocks to microwaves and cars. Some analysts call semiconductors the oil of the 21st century. If so, then the U.S. last fall initiated against China a digital version of an oil embargo, except this embargo involves only the most advanced chips.

Like many countries, the U.S. has always jealously guarded its most advanced technology, strictly supervising exports of military tech and commercial products that could have military applications. With regard to China, it has also used a “sliding scale” that would allow exports of military-related products as long as they kept the U.S. two generations of technology ahead. But in a September speech, U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan outlined broader constraints on U.S. exports to China, including all advanced chip and supercomputing technologies, even if they have no military application, and eliminating the sliding scale, saying that U.S. tech should remain as many generations as possible ahead of China.

Less than a month later, the Biden administration banned U.S. companies from selling their most advanced chips and chipmaking technology to China. Even non-U.S. companies will no longer be allowed to sell their chips or machines to Beijing if they contain U.S. components or were made with U.S. equipment. The administration also barred American citizens, permanent residents, and green card holders from working for Chinese semiconductor companies. In December, the administration added 36 Chinese and Chinese-affiliated firms to its list of companies that no one, even foreign companies, should sell U.S. equipment to without first getting a license from Washington.

“China will be meaningfully behind”

These restrictions represent a huge blow to Beijing’s ambitions to lead in certain technologies, such as supercomputers and artificial intelligence, and to create a military that’s second to none.

“They need chips and components for all the information, infrastructure, computers, and command-and-control systems that they’re trying to put in place to become a modern, high-tech joint force,” says David Finkelstein, director for China and Indo-Pacific security affairs at CNA, an independent research institute based in Arlington, Virginia. “So they’ve got to have access to the best technology out there. And if they can’t get access to it, they need to figure out how to develop it on their own.”

Even during the friendliest of times, China struggled to keep up with the West in semiconductors. Its leading chipmaker – Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. – remains an estimated five years behind its Western competitors. Now, the West’s embargo will make catching up that much harder.

“China will be meaningfully behind at least for the next half decade and probably longer,” Christopher Miller, a historian at Tufts University’s Fletcher School and author of a new book “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology,” writes in an email.

From Washington’s perspective, such moves are overdue to counter a growing rival that doesn’t play by the rules. It accuses China of illegally pursuing territorial claims in international waters, mistreating its minorities, routinely stealing Western technology, and manipulating trade to further its own ends without the win-win reciprocity that Western nations expect.

From Beijing’s perspective, America’s moves affirm long-held fears that Washington is out to keep the world’s second-largest economy from assuming its natural position in the world.

Can China find a new path on chips?

The problem for China is that, in the short term, at least, it has few options to counter such moves. One reason is that semiconductors represent a far more complex challenge than most of the technologies that China has mastered so far. And it is a striking example of the kind of win-win globalization that the West practices and that Beijing is suspicious of.

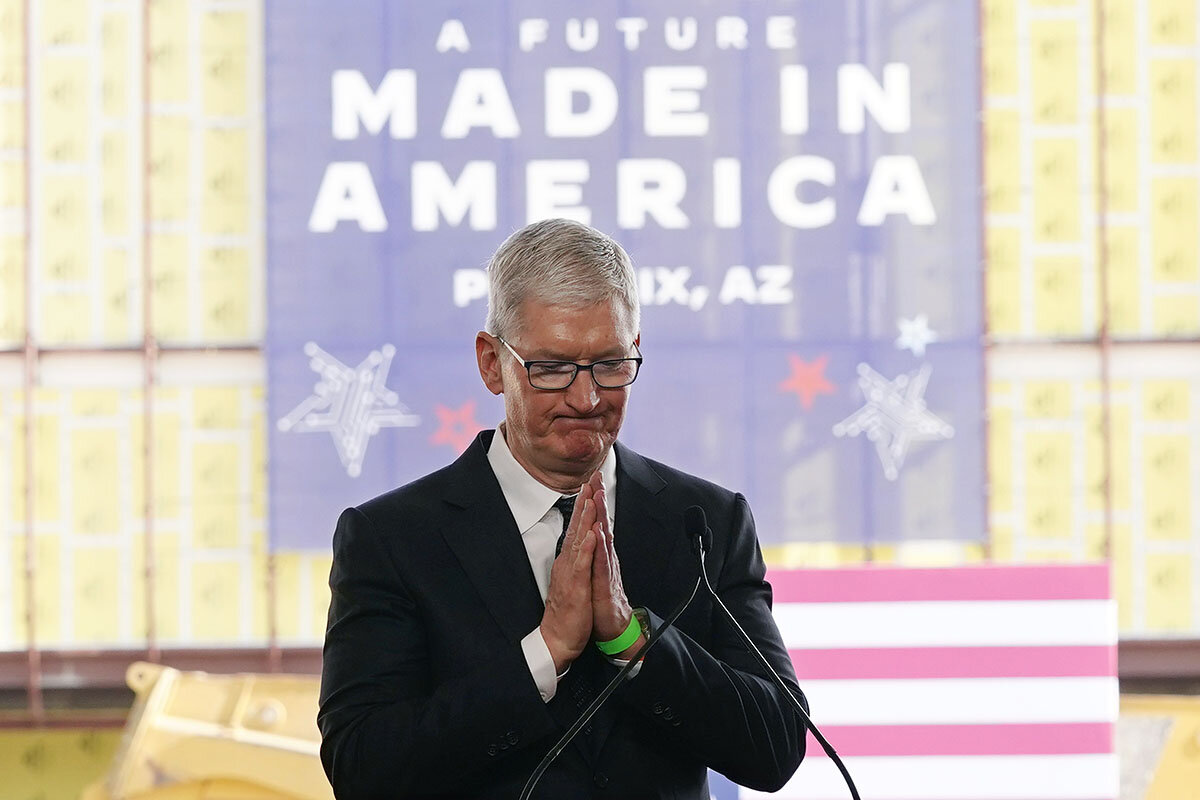

To begin with, making advanced chips involves an international supply chain that no one country dominates, even the U.S. Thus, a chip in an iPhone might be designed in the U.S., the United Kingdom, and Israel; manufactured in Taiwan with machine tools from the U.S., Japan, and the Netherlands; and packaged in Malaysia, points out Dr. Miller. Trying to replicate that chain domestically would bankrupt China, he adds.

Beijing could invade Taiwan and take over the world’s most advanced chip fabricator, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., but even if the factory survived the attack, China wouldn’t retain the know-how and would certainly lose any access to the other vital pieces of the system.

It can try – and is trying – to convince Europe to ignore America’s technology ban. But Europe sells far more goods to the U.S. than it does to China and shares America’s wariness of Beijing’s intentions. Last June, for the first time, NATO listed China as a strategic challenge to its “interests, security and values.”

Beijing could threaten to cut off Western firms from its huge market, which would devastate some companies but inflict far more damage on China’s economy. European purchases of Chinese goods are responsible for 16 million Chinese jobs while Chinese purchases of European goods produce relatively few European jobs, says Mr. Wuttke of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. “China in many ways is more dependent on Europe than we are dependent on China.”

Many Western companies, suddenly aware of their dependence on China, are also diversifying their supply chains to include other countries.

For Chinese President Xi Jinping, these trends create a worrying dilemma. Accepting the demands of globalization may force policy compromises and continued reliance on the West that he does not favor. Turning away from globalization after so many years of rapid development would almost certainly mean slower growth and loss of access to Western technology.

“China is richer, stronger, healthier, safer, cleaner than it’s ever been,” says Scott Kennedy, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. “Yet from Xi Jinping’s point of view, they’re more vulnerable than ever.”

Challenges for the U.S. too

For the U.S., too, a decoupling from China poses risks. For one, there are no guarantees that America’s semiconductor allies, such as Japan and the Netherlands, will go along with the advanced chip embargo. Thus, a tough stance against Beijing may simply hand business to non-U.S. chipmakers. For another, there are drawbacks to completely isolating Beijing from Western technology.

“There are commercial advantages and national [interests] to having the Chinese in your own technological ecosystem and in the hierarchies that Western companies lead,” Dr. Kennedy adds. “Those hierarchies are very difficult to change. And you gain a lot of information about China’s capabilities by having them in those hierarchies with you. And you also, by 40 years of interaction, raise the costs for China to go to war with you.”

For the moment, it’s big Western and Chinese corporations that have the biggest incentive to try to find a new equilibrium in Western-Chinese relations. In September, after months of effort, the European Chamber of Commerce released an in-depth report with 967 recommendations for how Beijing could help European companies flourish in China. “Our members, for whatever reason, have not given up yet,” says Mr. Wuttke. “They still believe that China can change.”