Generosity united the South in the aftermath of 2011 superstorm

Loading...

Tweets, text messages and Facebook posts are more than just addictive and pesky mainstays of modern life. When disaster struck the South in the spring of 2011, technology revealed its power to unite a region in grief and generosity.

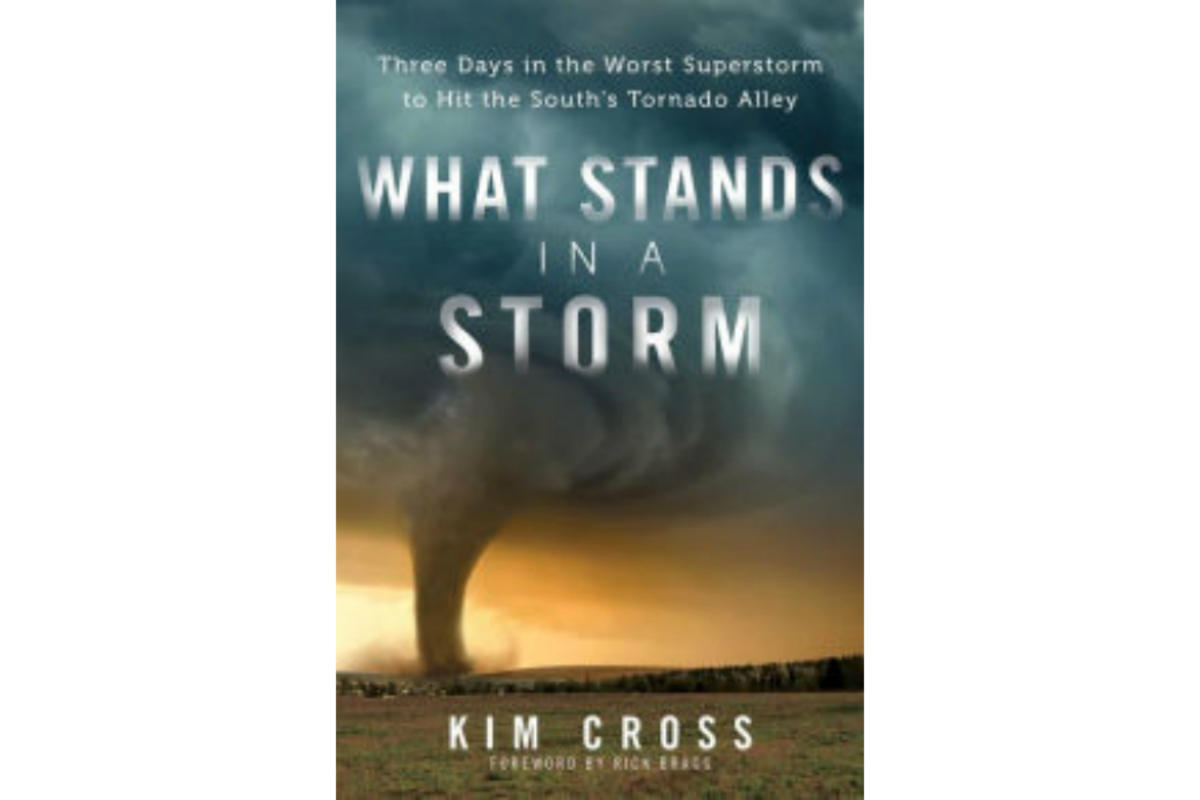

Nobody understands this better than journalist Kim Cross, author of the riveting new book What Stands in a Storm: Three Days in the Worst Superstorm to Hit the South's Tornado Alley.

When a tornado tore toward her Birmingham, Ala., home, she huddled in a laundry room with her family and her smartphone, furiously searching for updates. Cross, then working for Southern Living magazine, soon found herself reconstructing a devastating tornado outbreak that left 245 dead in Alabama alone. Sheād uncover the remarkable power of tweets and texts to bring people together and keep them safe ā before, during and after the storm.

Thatās not all. With deep sensitivity, Cross powerfully profiles the TV weathermen who try to warn the public despite ever-present false alarms, the scientists furiously working to better predict tornadoes, and the grieving residents trying to fend off despair through community and faith.

āPeople looked for miracles and found them, and that gave people a lot of strength to get through it,ā Cross says in an interview with the Monitor. āBeautiful things come from brokenness. The things that tear our world apart can bring us together.ā

Ģż

Q: Readers from elsewhere may be surprised to learn that the Deep South ā āDixie Alleyā ā is a hot spot for tornadoes. How does that region compare to the Midwest and Tornado Alley?

Ģż

The Midwest has a greater number of tornadoes, but the South has more big ones. When spring rolls around, itās part of living here, something that everyone eventually gets used to. Itās sort of like earthquakes in California: You know they happen, but you donāt think about it every day.

I grew up in both California and Alabama, and I remember having to do very much the same thing in school. In California, you have an earthquake drill where you get under your desk. In Alabama, you get in the hallway, tuck into a ball and cover your head with your fingers.

Ģż

Q: What are some differences between tornadoes in the Tornado Alley and the Southās Dixie Alley?

Itās a lot safer to chase tornadoes out there in the Midwest because roads are in a grid pattern. In the South, particularly in Alabama, the roads are winding. Birmingham and Northern Alabama are in the foothills of the Appalachians, and the roads spaghetti all over the place. You rarely see the horizon, and it makes it very dangerous to chase tornadoes because you canāt assume that the road youāre taking will get you out of the way.Ģż Also, here tornadoes tend to be rain-wrapped: The funnel can actually be hidden behind a curtain of rain.

Ģż

ĢżQ: What is the state of tornado forecasting?

Ģż

Forecasters can detect conditions when tornadoes form, but that doesnāt necessarily confirm a tornado. The only way to confirm a tornado is for someone to lay eyes on it.

The huge dilemma of forecasters is that they can see a signature of what looks like a tornado, but it may or not be, and they have to make a call about whether they want to warn about it. If they do issue a warning, it could a false alarm and increase peopleās complacency. But if they donāt warn about it, people die.

Since the 2011 superstorm, theyāre usingĢż more dual-polarization radar, which allows you to not only detect the presence of some kind of matter in the air, whether itās bugs or precipitation, but actually see an indication of the shape of it. A meteorologist can look at a radar screen and say āthatās rainā or āthatās debrisā with a greater degree of confidence.

Ģż

Q: What happened when the tornado came near your home?

Ģż

We were hearing about storms a week ahead of time, and we knew theyād be bad. I remember seeing the first tornado of the day on live camera, and then we watched as the big one headed toward Tuscaloosa.

I was sitting with my husband and my son, who was then 3 or 4, thinking, āOh gosh, this doesnāt feel real. People are dying right now.ā You feel like youāre watching a movie, and someoneās playing a trick on you.

Weāre watching it with great trepidation, then sirens start wailing and the power turns off. Thereās this horrible silence when all the sounds youāre used to grind to a halt. We went into our safe room, a laundry room at the center of the house with no windows and away from doors. I remember getting my phone out, and at some point the forecaster called out my neighborhood. It got really scary. The tornado came about 7-10 miles away.

Ģż

Q: What struck you about how people reacted to the tornados?

Ģż

I was impressed by the speed at which people started rescuing each other. The authorities did a great job, but people didnāt wait. They just started digging for each other and helped strangers. In the immediate aftermath and the recovery, I found that really touching.

Ģż

ĢżQ: How did social media change how people reacted to the tornados?

Ģż

You have many more sources of information. You can watch TV on your phone, you can follow tweets of people, and alert your friends and family. After the storm, the phone lines might be down or overloaded, but a text can get through when a phone call canāt.

Facebook and Twitter became mechanisms of spreading word about relief needs and supplies. It really changes the way people give. Before, if you wanted to help, youād write a check and send it to the Red Cross. Now, someone can say āWe need diapers in Alberta City,ā and you could see that and respond to it and say, āIām on the way.ā You could meet the person who needed it face to face.

That was a point of healing for both sides. You want to help, and it feels better to know you can help this young mother and hug her instead of giving money to a faceless organization. That made it deeply personal.

Ģż

ĢżQ: Did any part of the reaction seem quintessentially Southern?

Ģż

The parking lots would fill with giant grills towed behind trucks and different church groups, people of different denominations and religions working side to side. The Methodists might do the prep, the Baptists the grilling, and another denomination handles delivery.

Sometimes you think, āthereās nothing I can do to make things better, but I can make a casserole.ā A woman in a little Mississippi town called Smithville that got devastated by a category F5 tornado rallied her friends, saying āI need cakes.ā Sixteen cakes came to her house, and they were just holding a sign that said āFree Food.ā

They kept trying to feed us. We kept telling them weāre not victims, we donāt deserve their food. But it made them feel good, and they wouldnāt let you leave without at least an ice-cold Coke.

Ģż

ĢżQ: What was it like for you personally to write the book?

Ģż

You feel squeamish and horrible asking people whoāve lost a child to relive the worst day of their life. But I was surprised at the healing that came through the stories both for the families and for readers.

Ģż

ĢżRandy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.