ŌĆśThe Emperor of GladnessŌĆÖ walks a tightrope between despair and hope

Loading...

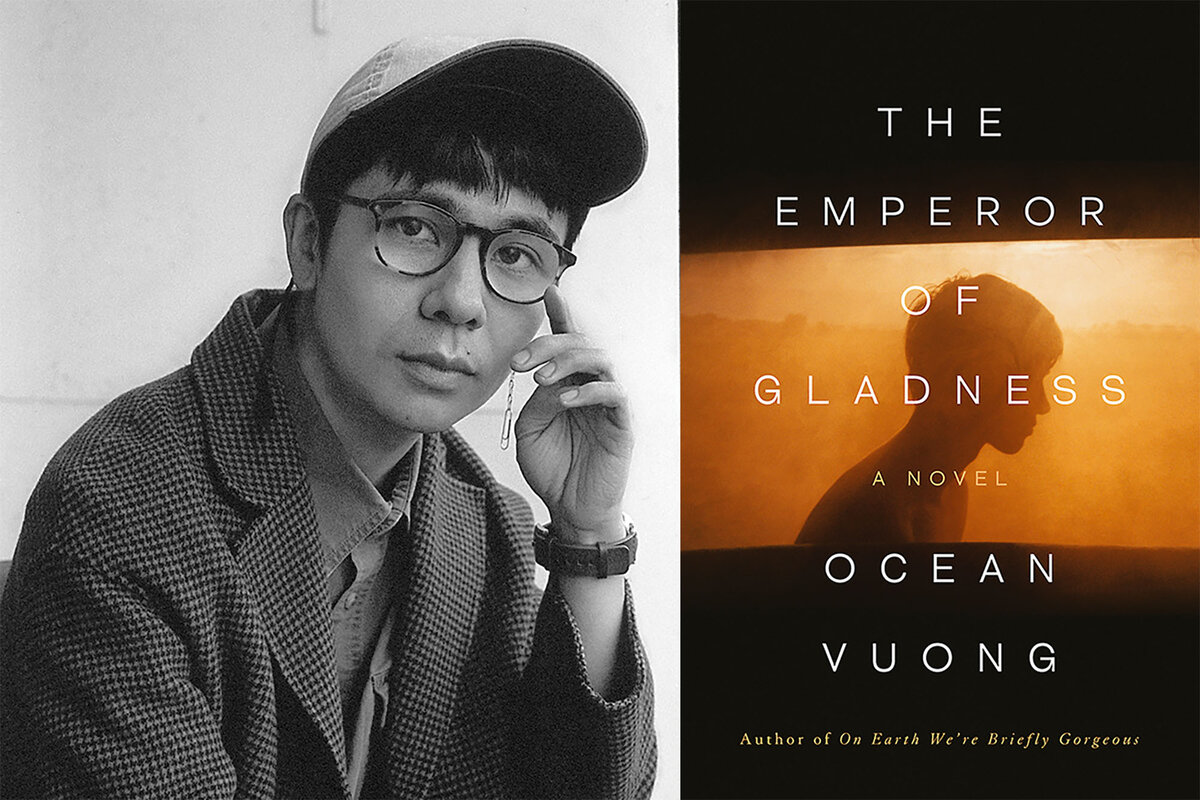

In 2019, Ocean Vuong, an award-winning Vietnamese American poet, stunned readers with his first novel. ŌĆ£On Earth WeŌĆÖre Briefly GorgeousŌĆØ was a brutal and tender coming-of-age story about surviving the aftermath of political and domestic trauma, written in the form of a sonŌĆÖs letter to his illiterate mother. In his unremittingly gorgeous second novel, ŌĆ£The Emperor of Gladness,ŌĆØ Vuong again deftly walks a tightrope between despair and hope, heartache and love.

For Vuong, fiction is a moral instrument, and he plays it with the practiced hand of a virtuoso. At the heart of his new novel is a bookish 19-year-old Vietnamese American ŌĆ£in the midnight of his childhood and a lifetime from first light.ŌĆØ

We meet Hai at a low point. Freshly out of drug rehab, he feels heŌĆÖs ŌĆ£run out of paths to take, out of ways to salvage his failures.ŌĆØ He doesnŌĆÖt want to further disappoint his mother ŌĆō a hardworking manicurist who thinks heŌĆÖs studying medicine ŌĆō and so he reasons, from atop a bridge, that thereŌĆÖs no shame ŌĆ£in losing yourself to something as natural as gravity.ŌĆØ

Why We Wrote This

Compassion and kindness motivate the actions of a 19-year-old man, whose troubled life is briefly redeemed by the care he gives an older woman. Our reviewer was captivated by the evocative writing and moved by the charactersŌĆÖ plights.

Hai doesnŌĆÖt jump, and he eventually finds a measure of relief in unexpected bonds forged with strangers, who become like family.

The first is with Grazina Vitkus, an 80-something World War II refugee from Lithuania who talks him down from the ledge and offers him shelter in her decrepit riverside house. Grazina misinterprets his name and calls him Labas, which is Lithuanian for ŌĆ£hello.ŌĆØ Hai later tells her that his name means ŌĆ£seaŌĆØ in Vietnamese, which of course evokes the authorŌĆÖs first name, Ocean.

Hai steps easily into a caregiving role: He picks up GrazinaŌĆÖs groceries (including her favorite frozen Salisbury steak dinners); he administers medications for her progressive dementia; he bathes her. When Grazina awakens with night terrors that carry her back to her teens in 1944 in Lithuania, which was under siege from both Nazis and Soviets, Hai joins in her dreamworld ŌĆō a trick he learned while caring for his grandmother who had schizophrenia. Fueled by what little he knows about the war from popular culture, he pretends to be an American infantryman named Sergeant Pepper who guides her to safety. By day, he anchors her in 2009 by repeatedly asking who the president is.

Hai finds another family in his co-workers at HomeMarket, the fast-food restaurant where the question of the hour, of every hour, is ŌĆ£How can I help you?ŌĆØ VuongŌĆÖs sympathetic portraits of this crew, each with their own problems ŌĆō medical debts, a sister in rehab, a mother in prison ŌĆō recall the big-box store workers in Adelle WaldmanŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Help Wanted.ŌĆØ Here, too, people who barely eke a living from their minimum-wage jobs band together to help each other, often by accompanying co-workers on far-fetched crusades.

ŌĆ£The Emperor of GladnessŌĆØ is set in fictional East Gladness, Connecticut, 12 miles outside of Hartford. Vuong vividly evokes the beauty of the depressed, postindustrial town in scene-setting descriptions that channel Thornton WilderŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Our Town.ŌĆØ VuongŌĆÖs narrator tells us: ŌĆ£Our town is raised up from a scab of land along a river in New England.ŌĆØ Earlier, the narrator says, ŌĆ£Mornings, the light rinses this place the shade of oatmeal.ŌĆØ He describes a ŌĆ£dried-up brook whose memory of water never reached this century,ŌĆØ and a wooden sign ŌĆ£rubbed to braille by wind.ŌĆØ And he urges us to ŌĆ£Look how the birches, blackened all night by starlings, shatter when dawnŌĆÖs first sparks touch their beaks.ŌĆØ

WeŌĆÖre told that no one stops in East Gladness, but readers will be stopped in their tracks by VuongŌĆÖs imagery: ŌĆ£We are the blur in the windows of your trains and minivans, your Greyhounds, our faces mangled by wind and speed like castaway Munch paintings,ŌĆØ he writes. ŌĆ£We live on the edges but die in the heart of the state. We pay taxes on every check to stand on the sinking banks of a river that becomes the morgue of our dreams.ŌĆØ

I had to read these pages several times before I was ready to move on.

But Vuong keeps his book flowing, like the river, like the traffic. ThereŌĆÖs heartache aplenty, and a troubling ending ŌĆō but also, amazingly, hijinks and humor, including GrazinaŌĆÖs belated realization that Hai is what she calls a ŌĆ£liggabitŌĆØ ŌĆō LGBT.

But itŌĆÖs the moments of tenderness youŌĆÖll remember, such as when Hai accompanies his Civil War-obsessed younger cousin, Sony, to therapy appointments and on prison visits to see his mother. Or when, after one of GrazinaŌĆÖs nightmares, ŌĆ£[Hai] reached over, across the half century between them, and cleared the stray hairs from her damp face.ŌĆØ

Life lessons begin with the novelŌĆÖs first line: ŌĆ£The hardest thing in the world is to live only once.ŌĆØ Grazina has another idea: ŌĆ£To be alive and try to be a decent person, and not turn it into anything big or grand, thatŌĆÖs the hardest thing of all.ŌĆØ Vuong borrows a line from Fyodor DostoyevskyŌĆÖs ŌĆ£The Brothers KaramazovŌĆØ ŌĆō one of the worn paperbacks Hai picks up in GrazinaŌĆÖs basement ŌĆō to bring home his point: ŌĆ£But donŌĆÖt be afraid of life,ŌĆØ HaiŌĆÖs mother tells her drug-addled, dissembling son. ŌĆ£Life is good when you do good things for each other.ŌĆØ