Not meant to soothe: How the truths of fiction can challenge and stir

Loading...

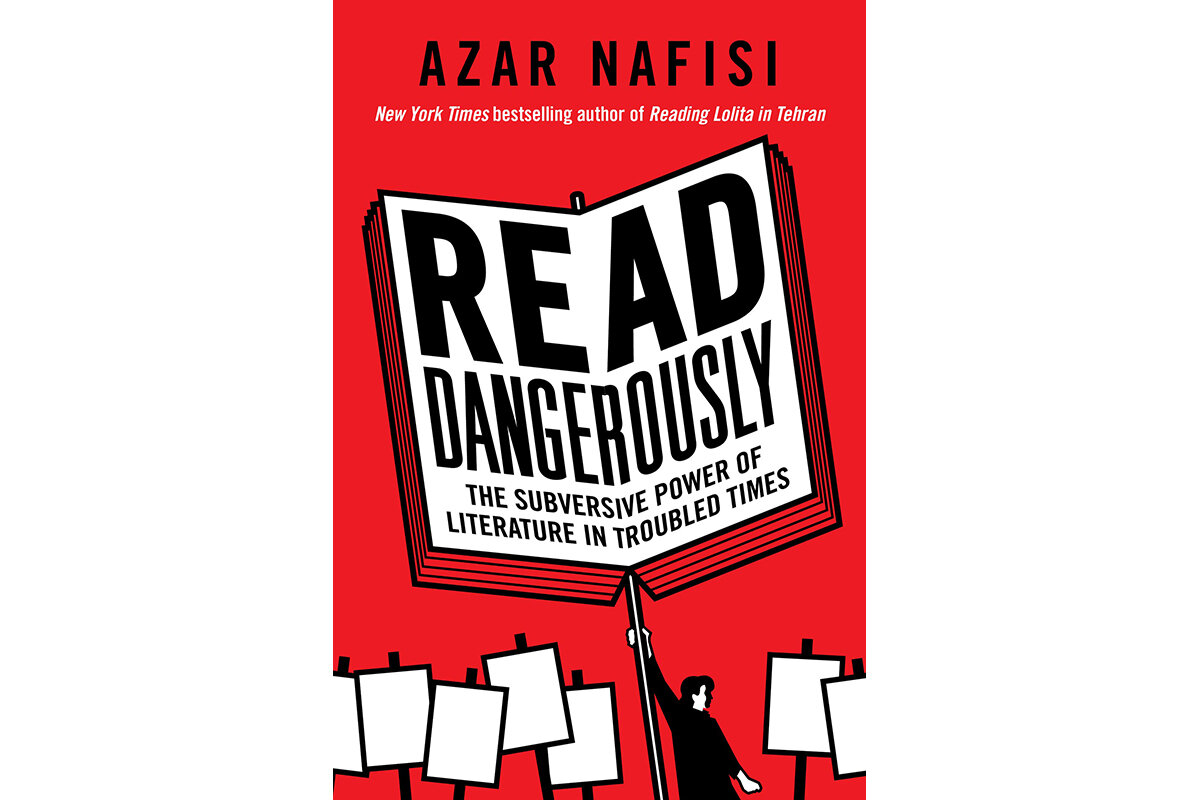

Azar Nafisi burst on the literary scene with “Reading Lolita in Tehran,” which recounted her efforts to teach Western literature to a small group of young women in Iran. A risky and challenging undertaking in that totalitarian state, but one that underscored, once again, the power of books to transform lives. In “Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times,” she once again writes about the power of the written word to shape the way we see the world – this time by focusing on the present moment.Â

Nafisi was born in Tehran, Iran, to open-minded and politically active parents. Her father served as mayor of Tehran for two years but was jailed for political reasons. Before his four-year imprisonment, he instilled in his daughter an abiding love of literature and stories. She was educated abroad, eventually earning a Ph.D. in English literature in the United States. Nafisi returned to Iran and taught there for 18 years before she was expelled from the university for failing to wear a veil. Eventually, she moved to America and became a citizen.Â

Through it all, she writes, “books and stories have been my talismans, my portable home, the only home I could rely on, the only home I knew would never betray me, the only home I could never be forced to leave. Reading and writing have protected me through the worst moments of my life, through loneliness, terror, doubt, and anxiety.” Â

“Read Dangerously” is written as a series of letters to her now deceased father. She explains how specific authors and books help her make sense of the world while simultaneously arming herself with arguments in opposition to the chaos she sees. This format allows her to neatly link essays that might otherwise appear unrelated. Â

She starts with “the allure and the dire threat of totalitarianism,” which she sees as exemplified by the fanaticism of the Islamic leaders in Iran and the rise of Donald Trump in America. So she dives into Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses,” Plato’s “The Republic,” and Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451.” This is not an immediately apparent grouping to most readers, but her thoughtful and insightful analysis of how these books spoke to her will leave many readers nodding in agreement.

In other cases, she explores authors that intuitively fit together. As an anecdote to her feelings of “frustration and despair” over the state-sponsored violence in Iran that killed hundreds of people in late 2020, she digs deeply into the writings of Zora Neale Hurston and Toni Morrison. She finds in them an unshakable commitment to personal dignity and a defense of “the right of every individual to exercise their independence of mind and heart.” Â

Not all the writers are as well known as Plato, Morrison, Rushdie, and Hurston. In a letter devoted to “the dehumanization and hatred that are intrinsic parts of war,” she considers Israeli author David Grossman, Lebanese writer Elias Khoury, and the much better known (at least to Americans) Elliot Ackerman, a U.S. Marine whose books focus on the people living in Iraq and Afghanistan, where he served five tours of duty. This letter is deeply personal for Nafisi because she lived in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War and writes that her memories of that time “are saturated with fear, with the anticipation of disaster.” Her assessment of these works feels even more heartfelt than the other letters.

Any account of our troubled times must include the COVID-19 pandemic. She suggests that America in 2020 resembled Margaret Atwood’s Republic of Gilead, so she devotes most of one letter to “The Handmaid’s Tale” and its sequel “The Testaments.” These dystopian novels lead Nafisi to consider the ways in which inhumanity becomes accepted – that is, that people “get used to even extreme violence and learn to live with it.” In the final chapter, she contemplates the murder of George Floyd and the protests that followed with a thorough review of the works of James Baldwin, one of her favorite authors. The letters are “a meditation” about her experience in both Iran and the U.S. Her focus is fiction because responding to the challenges the world faces “requires understanding, and for that we need the imaginative power that fiction cultivates.” But not just any fiction – she is focused on “challenging literature.” Too many Americans, she finds, “see reading solely as a comfort, seeking out only texts that confirm our presuppositions and prejudices.” Because change can be a daunting process, we avoid “reading dangerously.” But that is precisely what she calls on us to do.