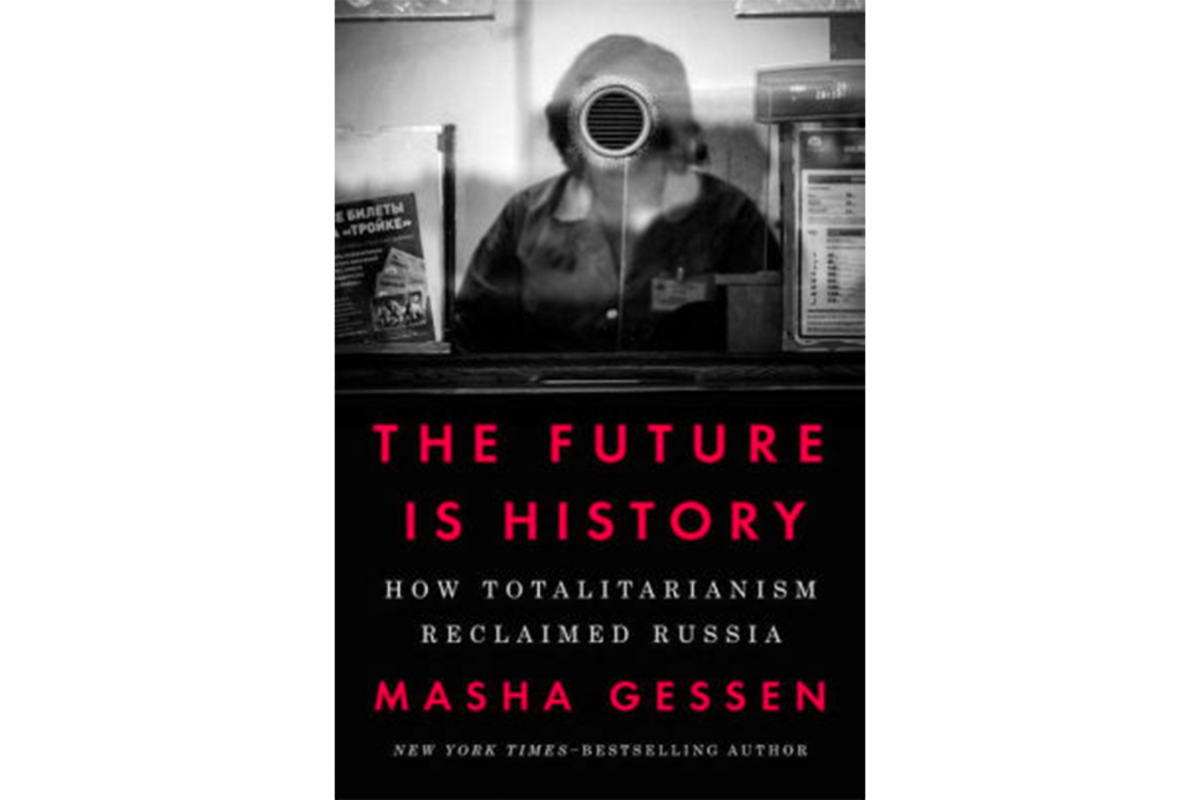

'The Future Is History' is a dark examination of what went wrong in Russia

Loading...

The future is history because, as the Russians say, “Budushego net," there is no future.

Masha Gessen, the sterling Russian-American journalist and activist, has been outspoken in recent press articles about the threat of totalitarianism in America. But in her latest book, Future Is History, she never mentions America’s problems.

Here, instead, she examines what is wrong in her native country and lets readers, wide-eyed, draw the parallels. She notes that, in Russia, “a constant state of low-level dread made people easy to control, because it robbed them of the sense that they could control anything themselves.”

The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, with various republics spinning off into their own situation-tragedies or into an alternative-reality show (i.e., Ukraine). What did Mother Russia have as soil in which to cultivate a new political system? “… Soviet institutions had become Russian institutions after 1991, and soon the Russian bureaucracy began to guard many Soviet secrets like its own.” Poisoned ground!

Gessen asks: “Had the ideas of freedom and democracy really been forgotten no sooner than they had apparently won?” Apparently so. Gessen delivers answers in her usual emphatic way: “Old government, Party, and KGB hands had filled the many voids at all levels of the bureaucracy and had resumed their ascent up the power ladder, as though the end of the Soviet Union had caused just a temporary layoff.”

Why should we care about how and why Russians lost the chance to purge the Soviet system from their souls? Why should we care about the earnest and hopeful intelligent young people who came of age in the new Russia and who slowly found themselves in the clutches of the Soviet zombies that have come back to power (not life, but power)?

Gessen was herself one of the hopeful, but she has preferred in this book not to discuss her own situation or her experiences trying to fortify a budding open society in Russia. She lost that battle to Putin when the Russian government passed laws allowing it to abduct children from gay parents, and she had to retreat to America for the sake of her marriage and children. The Russian government seems to want to pretend that gay people (not corruption, violence, racism, religious and cultural intolerance, economic inequality, alcohol, and drug abuse) are the primary source of the nation’s ills. However, charges Gessen, much of the inspiration for such cruel bigotry was imported from America. She writes that Russian homophobes love the American academic Allan Carlson’s “World Congress of Families,” a ���Ǵ��� group “dedicated to the fight against gay rights, abortion rights, and gender studies.”

Gessen takes turns focusing on four particular earnest brave resisters to the totalitarianism of their country, Zhanna, Masha, Seryozha, and Lyosha. It never becomes exactly clear, though, why Gessen chose these four. She seems to have known them all for many years, since their childhoods, but are they random representatives of Russian life? No. They’re more similar to Greek mythic tragic heroes, like Antigone, Electra, and Orestes – smart and capable, admirable for their persistence and integrity, and for their necessary courage in opposition to tyranny.

Zhanna’s father, Boris Nemtsov, a politician regarded as dangerous by the Kremlin because of his faith in democracy, was assassinated in 2015 in front of Red Square, his murder covered up by the government. Lyosha, a careful, cool, optimistic gay rights advocate and sociology professor, has had to move to New York for fear of his life. This is a grim book.

In her attempt to define the requirements of a totalitarian system, Gessen quotes a priest who fled Mussolini’s fascist Italy: “Everyone must have faith in the new state and learn to love it. From the schools up to the universities conformity of feeling is not enough; there must be an absolute intellectual and moral surrender, a trusting enthusiasm, a religious mysticism where the new state is concerned.…”

The dictator-president Putin’s cynical play to nationalism has created a swamp of intolerance, and the country has taken on a fearful though familiar ugliness, bringing back Soviet-style denunciations, censorship, and self-repression. If the thugs would only leave people their privacy. But no, those who stand out and speak up for social justice, for religious tolerance, for democracy, risk being denounced and losing their jobs or being beaten and jailed.

A pioneer in Russian psychoanalysis, Marina Arutyunyan, one of Gessen’s primary sources, diagnoses Mother Russia as depressed and suicidal, which leads to Gessen’s conclusion: “This country wanted to kill itself. Everything that was alive here – the people, their words, their protest, their love – drew aggression because the energy of life had become unbearable for this society. It wanted to die; life was a foreign agent.”

All of which leaves the reader asking: Can Russia save herself? It's not clear that even the courage of resisters like Zhanna, Masha, Seryozha, and Lyosha offer grounds for cautious hope.

Bob Blaisdell is writing a biography of Tolstoy.