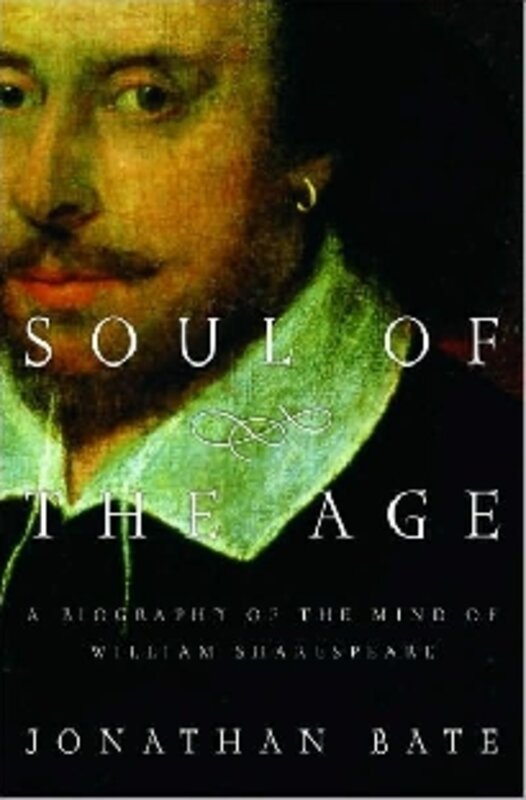

Soul of the Age

Loading...

As usual, George Bernard Shaw said it first and got it right: “Everything we know about Shakespeare,” he pointed out, “can be got into a half-hour sketch.”

Jonathan Bate begins his new book, Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare, by acknowledging this truth. We know so little about the man (outside of his texts – assuming that they really are his) and that little has been worked over relentlessly for centuries now. Is there really anything more to be said?

The answer is yes, and there will always be. Bate’s approach is to focus on Shakespeare as “the Soul of [his] age” (a line of posthumous praise heaped on Shakespeare by contemporary Ben Jonson.)

In this book Bate (an academic with impeccable credentials as both a Shakespearean historian and critic) considers Shakespeare as a man of his times, focusing on both the ways in which he was shaped by the intellectual currents of his era and the ways in which he stood apart from them.

Setting Shakespeare in historic context, of course, is not a novel idea. But Bate is a skilled guide through complex territory. He knows his history, but even better he knows his Shakespeare and he does a good job of tying the two together.

Bate takes the “unifying image” of his book from Shakespeare himself, considering the Bard at each of the “seven ages” of man spelled out in “As You Like It”: the “mewling and puking” infant, the “whining schoolboy,” the “sighing” lover, the “bearded” soldier, the justice with the “fair round belly,” the “lean and slippered pantaloon,” and finally “the last scene of all.”

This conceit works better in some places than others but at least it gives “Soul of the Age” a focus and helps to keep it accessible to general readers. And particularly in the early chapters, the method yields some lovely results.

In the “Infant” section, Bate reminds us that Shakespeare was born into “the herbal economy of rural England.” Although we often associate Shakespeare with the “glorious court” and “bustle” of Elizabethan London, he was also very much a man of “the rivers, hills, and woods, where the names of the villages nestle among the natural features of the landscape.”

In fact, Bate makes a convincing case, Shakespeare is in part responsible for the “invention” of our concept of “deep England.”

The “Schoolboy” chapters make a lively read as well. Bate considers the texts Shakespeare was likely to have studied in school and reminds us that “the idea of education” is “the essence of northern European humanism.” It makes it seem very natural, for instance, that “The Tempest” would have been built around the question: “What do we have to learn from books?”

In thinking about Shakespeare as “Lover,” Bate treads some of the same ground recently worked over by Germaine Greer in her book “Shakespeare’s Wife” about Anne Hathaway.

Both Bate and Greer examine records of the era, and although they disagree on some particulars, they converge on the main point: Despite years of myth built up around the subject, there is no real evidence that Shakespeare’s wedding to Anne was a shotgun wedding.

But when it comes to understanding Shakespeare as a lover, Bate is left in the same blind corner as the Bard’s other biographers. Shakespeare’s works tell us that their author knew love both as a deeply emotional participant and as a detached, bemused observer. But to go any further is mere speculation.

The ‚ÄúSoldier‚Äù section of the book offers some interesting commentary on the north-south (Protestant-Catholic) and east-west (Islamic-∫£Ω«¥Û…Ò) splits that shaped Shakespeare‚Äôs age. Bate also looks at Shakespeare‚Äôs plays as chronicles of England‚Äôs shift from ‚Äúthe old code of honor to the new politics of pragmatic statecraft.‚Äù

The book’s last sections, unfortunately, drag a bit. Bate’s conjecture, for instance, that during his “lost years” (1585-92) Shakespeare may have undergone “some kind of rudimentary legal training” feels just like that – conjecture.

It is also difficult to connect Shakespeare to the late “ages of man” as he died at the age of 52 (after, the story goes, a night of hard drinking with his friends).

But for readers eager to explore Shakespeare as a thinker rich in the qualities most valued by this age – shrewdness, acuity, and understanding – Bate’s book has much to offer.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was also right when he said, “Shakespeare is the only biographer of Shakespeare.” But at least Bate knows his material well enough to point us in the right direction.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor‚Äôs book editor.¬Ý