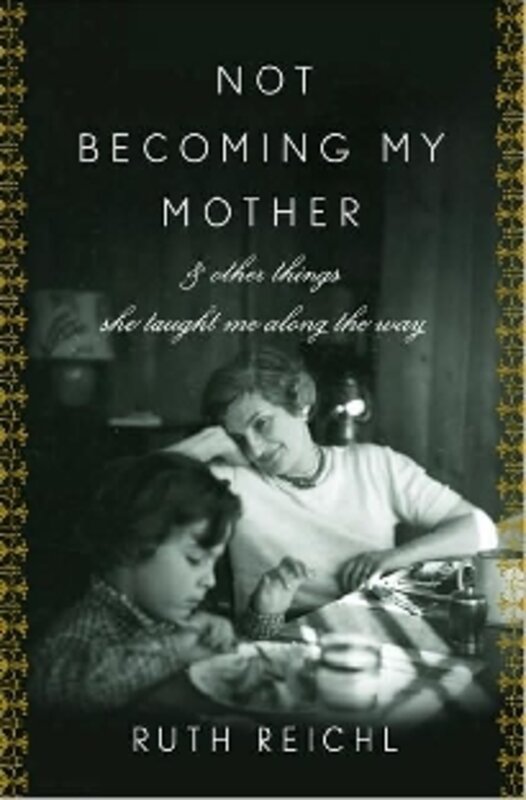

Not Becoming My Mother

Loading...

Ruth Reichl has been dining out on stories about her mother for years. The hilarious opening chapter of her first memoir, “Tender at the Bone” (1998), recounted how her mother, “The Queen of Mold,” accidentally poisoned two dozen people at a party. Young Reichl became a self-appointed watchdog, warning guests off her mother’s more dangerous concoctions.

With Not Becoming My Mother, Reichl, editor-in-chief of Gourmet magazine and former restaurant critic for The New York Times, attempts to atone for having disloyally mined the mother-lode for entertaining material. The book is essentially a posthumous, left-handed Mother’s Day card to Miriam “Mim” Brudno Reichl.

In it, her only daughter thanks her for providing such a strong negative example “of everything I didn’t want to be.”

Reichl isn’t just referring to her mother’s lamentable culinary skills. The lesson Mim imparted went far deeper: Not working causes misery all around. What Reichl took away from her mother’s unhappy life is that the key to fulfillment is meaningful employment.

Reichl comments that “to this day I wake up every morning grateful that I’m not her. Grateful, in fact, not to be any of the women of her generation ...”

This sounds harsher than it actually is, for the remarkable thing about Reichl’s slim book, which grew out of a talk she gave honoring the hundredth anniversary of her mother’s birth, is her determination to see things from her mother’s point of view. She does this by excavating her mother’s personal papers and letters.

What she finds is a woman who was “more thoughtful, more self-aware, and much more generous” than the comic character featured in her Mim Tales.

Reichl boils down her mother’s difficulties to her acquiescence to societal and familial pressures not to pursue a career. Mim later rued her eagerness to please her parents, who considered marriage the end-all and be-all for women.

Reichl comments: “Good women didn’t work if they didn’t have to; it would only humiliate their husbands ...” The result, she said, was a whole generation of smart, educated, bored, miserable women, “a terrible waste of talent and energy.”

Her mother was bright but no beauty, not a winning combination in the marital meat market.

Reichl was taken aback to find a cruel letter from her grandfather dissuading her mother from following him into medicine: “ ‘You are a dear girl,’ my grandfather had written, ‘and you have a fine mind. But you will have to resign yourself to the fact that you are homely. Finding a husband will not be easy.’ ”

With encouragement like that, Reichl says, is it any wonder that her mother held such a low opinion of herself and plunged into a predictably disastrous first marriage?

Among the things Reichl thanks her mother for is giving her the freedom to disobey her. The implication is that if Reichl had received such a letter, she probably would have ripped it to shreds – or used it as literary fodder.

In fact, when her mother – as a test – addressed a letter to her recently married daughter as Mrs. Douglas Hollis, Reichl sent it back, unopened, as she’d said she would. Finding that, too, among her mother’s papers, she discovers that her mother had expected her to return it and had written the letter to herself, a pep talk listing her mistakes and urging herself to stop looking back and start moving forward.

With the rose-tinged clarity of hindsight, Reichl concludes that “my mother deliberately sabotaged my respect and emphasized her failings. She loved me enough to make me love her less. She wanted to make sure that I would not follow her footsteps.”

This is, no doubt, a consoling interpretation of her mother’s woeful behavior, and it sure beats bitterness. But was her bipolar, willfully eccentric, over-medicated mother, a “tsunami of pain,” really in control enough to “willingly” make this “enormous sacrifice?”

Readers of Reichl’s columns and previous books about her culinary and personal adventures, including “Comfort Me With Apples” and “Garlic and Sapphires,” know that she is an irresistibly engaging, natural storyteller.

“Not Becoming My Mother” is more didactic, pitched at inspirational fervor over entertainment. On a mission to convey the unequivocal lessons she gleaned from her mother – “those who are not useful can never be satisfied,” and “in the end you are the only one who can make yourself happy” – Reichl reduces her story to a clear broth that is simple enough to spoon into children, yet bracing enough to fortify everyone.

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a regular Monitor contributor.