Measuring up: Why humans want to quantify everything

Loading...

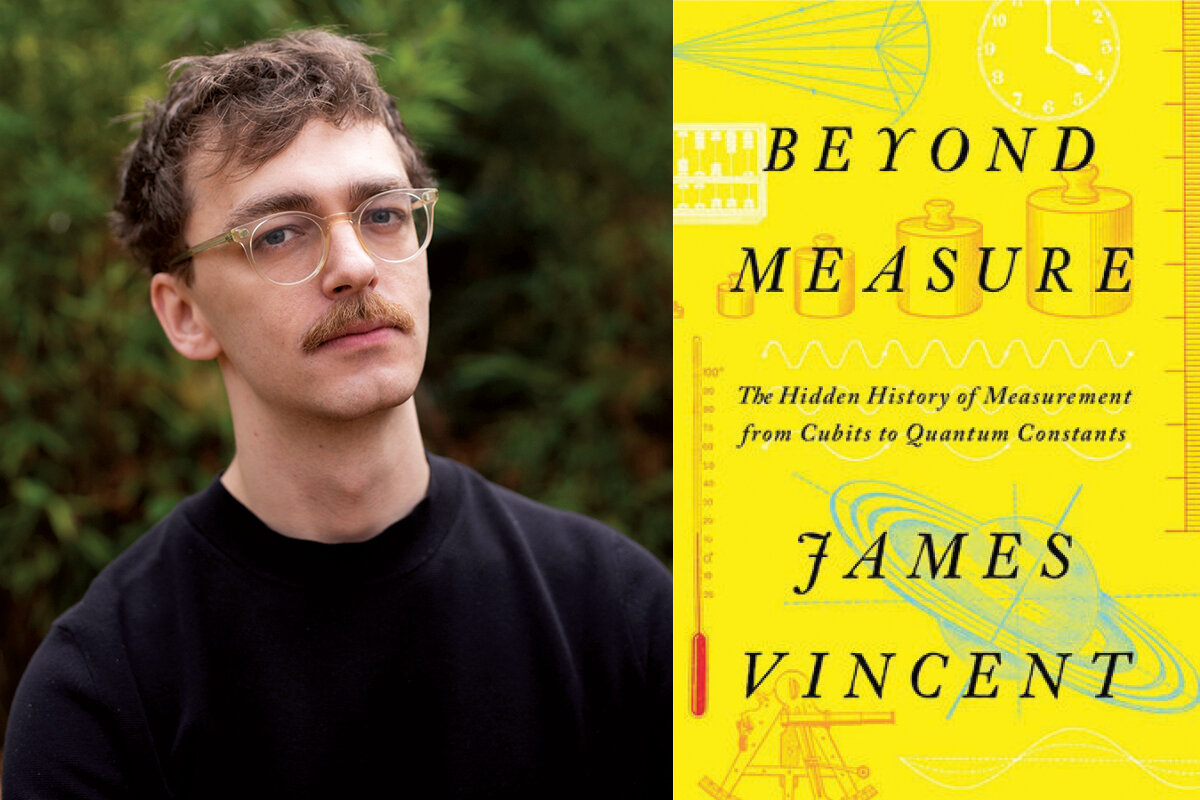

When we talk┬Āabout what ŌĆ£counts,ŌĆØ we mean what matters. How numbers shape worth is a key question in ŌĆ£Beyond Measure: The Hidden History of Measurement From Cubits to Quantum ConstantsŌĆØ by James Vincent, a senior reporter at The Verge. In the book, he metes out a social history of the human desire to quantify. He also makes the case that stats are far from static ŌĆō theyŌĆÖre personal and political. ŌĆ£Beyond MeasureŌĆØ demonstrates that measurements are as malleable and fallible as the humans who made them. Mr. Vincent spoke by video chat with the MonitorŌĆÖs Sarah Matusek.┬Ā

What is your favorite thing to measure?

Time. I mean, itŌĆÖs not my favorite thing, but I think itŌĆÖs the thing that engages me most consistently, confuses me, and challenges. ... IŌĆÖm a man of lots of checklists.┬Ā

It sounds like your 2018 reporting on the redefinition of the kilogram inspired ŌĆ£Beyond Measure.ŌĆØ At what moment was your interest in pursuing this book sparked?┬Ā

I think the initial spark was just finding out that the kilogram existed. It had never crossed my mind before that there might be a physical kilogram. ... It was that sort of realization that something as seemingly fundamental in our lives was arbitrary, was entirely invented ŌĆō not only invented but required maintenance. That was the moment where I sort of volunteered for this trip [to France] to go see the debate about the definition of the kilogram. ... This is of course the International Prototype of the Kilogram, the IPK or ŌĆ£Le Grand K,ŌĆØ as itŌĆÖs been nicknamed by its keepers, which is this platinum-iridium cylinder, about the size of an egg, making this very dense and durable metal that for more than a century was used to define the kilogram. [The kilogram is now defined based on a constant of nature.]

Our earliest units were derived from ourselves, as you note, like the cubit based on the length of the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. Do you see traces of this ancient innovation in present-day measures?┬Ā

Absolutely. ... YouŌĆÖre measuring a new piece of furniture, you immediately go, ŌĆ£Ah, is it about this big? Is it about as wide as my arms?ŌĆØ You do a fathom without even thinking about it. I think our bodies are just obviously the natural arbiters for measurement, because everything we need to measure needs to make sense to us.┬Ā

Did the book change how you think about data as a journalist who covers technology?

It made me much more suspicious, absolutely. ... For example, when you look at the business use cases of measurement, there are so many reasons to be suspicious about statistics and figures that we are given by companies that only they can measure.

Q:┬ĀYou offer frequent reminders of how scientific progress is a double-edged sword. Statistics advanced public health but also paved the way for eugenics. Is there any recently adopted innovation whose implications concern you?┬Ā

Artificial intelligence. ... IŌĆÖm writing about its use in academia and whether the ability to use tools like that to write essays on command will erode part of the educational system ŌĆō the way in which we learn, the way in which we teach. ... All sorts of automated systems that are used in policing, that are used in health care, and that are used to make predictions of the sort that statistics first made possible ŌĆō to predict who needs help, who might re-offend and therefore adjust their sentence, how long theyŌĆÖre going to spend in jail. I think those are very dangerous, because they take human agency out of the system.┬Ā

When I think about the big history of measurement, I call it a history of increasing abstraction. The measurement starts, as youŌĆÖve mentioned, as something thatŌĆÖs very close to the body, very close to nature, that is sort of fundamentally relatable on an individual level. Forces of digitization, of globalization, mean that we measure at a distance, and every time we measure at a distance, we lose connection to the subject.