How do you teach third-grade math?

Loading...

This is part 7 of a year-long project - to see the full story go to

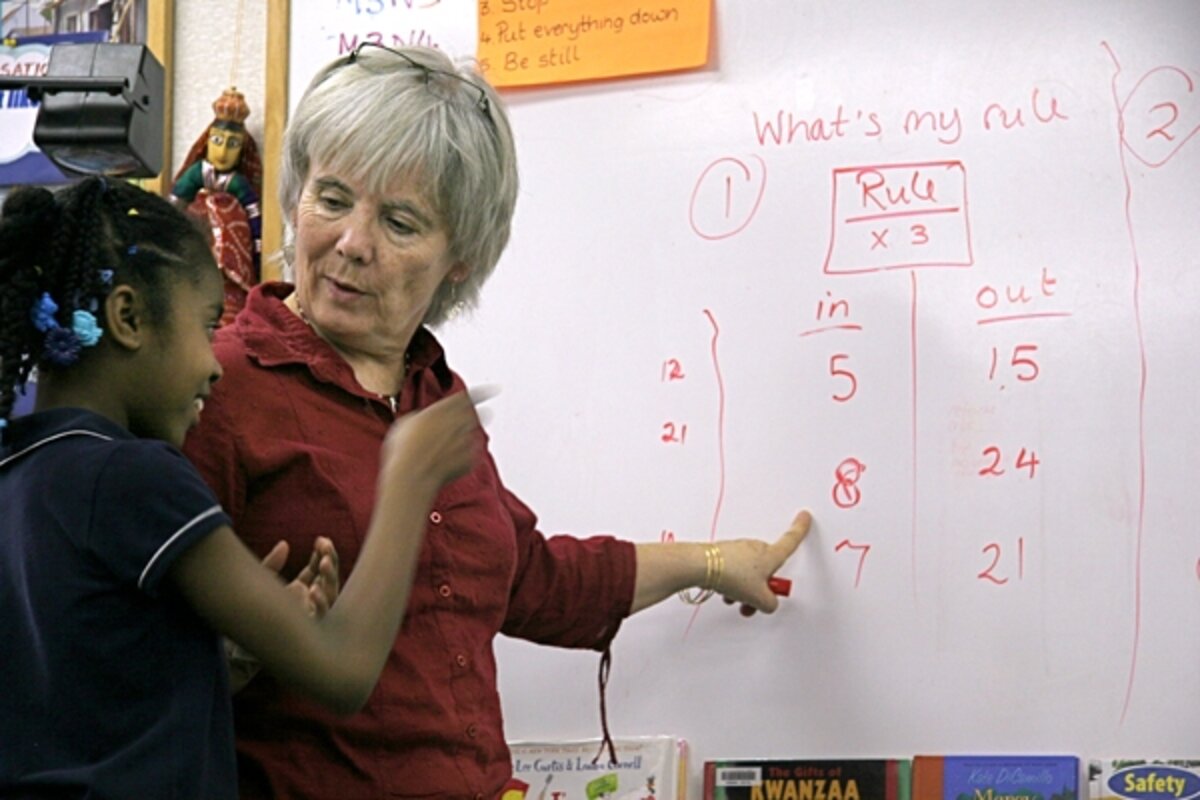

Some of her kids can multiply dozens; some are still adding on their fingers. Some, by Georgia standards, are failing third grade math. But today, whatever Ann Griffith’s students know about division, they’re fired up about it.

A dozen 8-to-10-year-olds sit cross-legged on the carpet of her trailer classroom, around their small, feisty teacher and the large rectangular white board on which she’s written:

Rule:

x3

in | out

__| 15

“Who can tell me?” Ms. Griffith asks.

A girl with wheels in her sneakers shoots a hand into the air. A curly haired boy looks lost. To one side, a kid whose contraband calculator Griffith confiscated a moment ago is looking around for fresh mischief. And from the vicinity of Griffith’s right foot, someone is squeaking.

“Ooh!” says Erin Harris, “Ooh, ooh!”

Since school began in August, Erin, a dedicated writer and artist, has been fearful of math. This winter morning, there are pushier students on the floor with their hands up, and kids likelier to get the problem right. There are hungry kids, distractable kids, kids whose families are suffering in this economy; 67 percent of students at the Erin attends receive free or reduced-price lunches. Half of the 400 students at the public charter school outside Atlanta were born overseas; many came to the US as and are struggling to master English. Erin’s not.

She’s just sitting on the carpet, hand in the air, unaware in her excitement that her torso and arm now form a 60-degree angle with the floor, bent by the force of an answer she’s sure she knows.

Griffith has a split second to calculate all of this and decide – in light of nearly two decades’ experience teaching in schools across the globe and four months getting to know these 12 students – whose name to call. It’s a problem with countless variables and no perfect solution. At this moment, Griffith reckons, Erin is the one in this third-grade math class who most needs to be right.

“Erin is bursting,” she says.

“Five!” says Erin triumphantly.

“That’s right,” Griffith says, filling in the answer on the board. “Now, how did you figure that out?”

“I knew it.” Erin can’t articulate what classmates leap to explain: She could have gotten the answer counting up by fives, or dividing three into fifteen. She’s not there yet.

But today, for the first time, Erin knows her threes. And it feels marvelous.

“You just knew it,” says Griffith solemnly, “Isn’t that cool?”

“Yeah,” says classmate Ross Wills, who mastered his times tables this fall, “she knows them by heart.”

It’s a pause, a breath in the lesson, to acknowledge Erin’s breakthrough. But Griffith can’t stop there. Because gears are turning in 10 other heads, and now Mateo Tewari, the curly haired kid who looked so lost a moment ago, has his hand in the air and wants to know: What if you had 4 plus 4 plus 4 plus 4? Would that be multiplying?

How do you teach third-grade math? Most of us, who learned it ourselves, assume we know.

This story continues .