Germany struggles with remnants of the Reich

Loading...

| Nuremberg, Germany

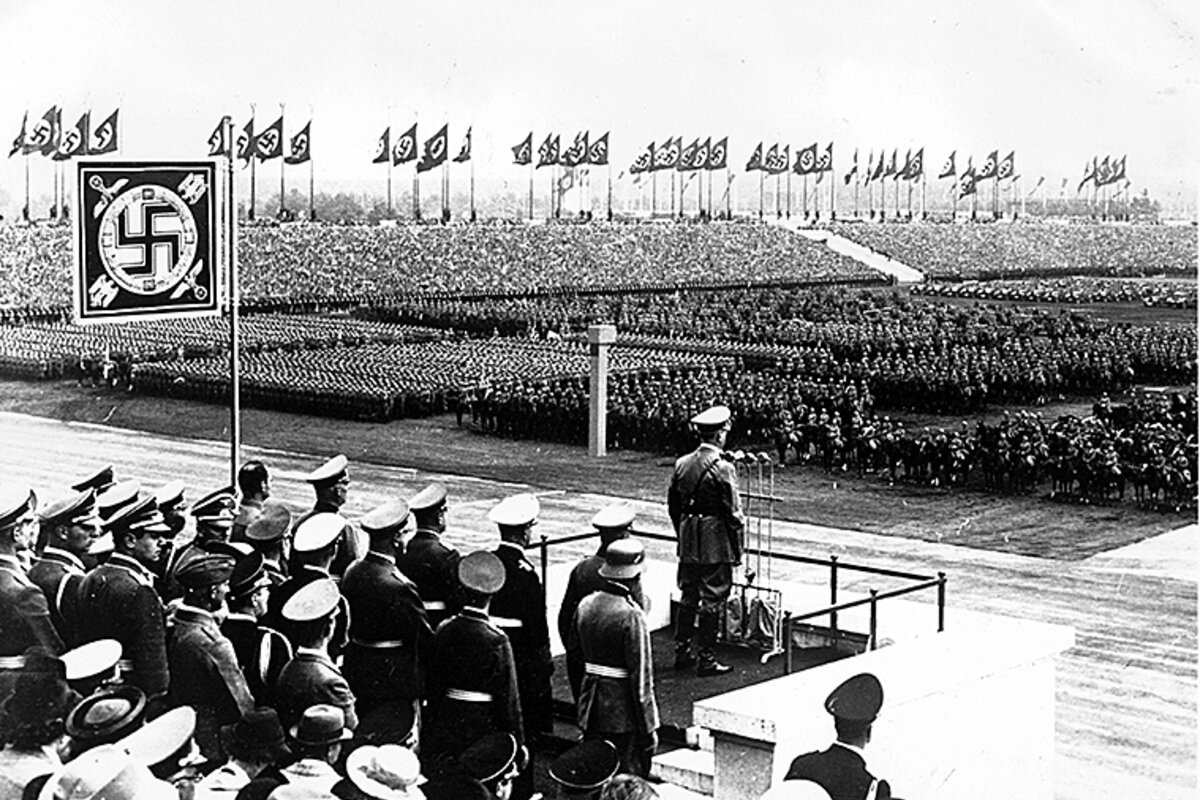

It doesn’t look like much. In fact, it’s easy to mistake the expansive parade grounds as a construction site, with all the fencing and warning signs, until you see the flashes from people taking pictures at the lectern. For it is here, at Zeppelin Field, where Adolf Hitler beguiled the masses in Nazi Party rallies held throughout the 1930s in this Bavarian city.

Nuremberg’s rallies, immortalized by Leni Riefenstahl in her 1935 film “Triumph of the Will,” have seared this city in the public’s consciousness as National Socialism’s ideological heart. While the swastika atop the grandstand of Zeppelin Field was famously blown up by the US Army in 1945, today these grounds stand as the best physical proof of Hitler’s ambitions for a thousand-year Third Reich.

For decades, most in this city preferred that these buildings simply disintegrate into the dustbin of history. And it shows. Walking along the grandstand, the length of three football fields, visitors are warned in German and English: “Enter at your own risk.” The stands are chipped and decrepit. Chain-link fences encircle much of the arena. Graffiti mars the podium where Hitler stood in his jackboots, spewing fiery rhetoric and pumping the air with his fist.��

Now the city is at a critical juncture as it debates the future of the Nazi Party rally grounds, raising questions as practical as they are philosophical. Nuremberg is in the midst of a pilot project to determine the final cost of refurbishing Zeppelin Field, the details of which will be made public by the middle of this year.

The city says that if nothing is done, the site will one day be too dangerous to visit. Ultimately, some historians argue, this gives Nazi architect Albert Speer exactly what he wanted: a mythical ruin. Others believe that old Nazi architecture merits not a single cent from the public purse. In their view, seeing it crumble is the boldest message that Germany could convey.

Nuremberg is not alone in dealing anew with its Nazi heritage. The entire country has been swept into a debate this year about the release of a new edition of “Mein Kampf,” the first time Hitler’s book has been published in Germany in 70 years. Both clashes come as Germany faces the reemergence of xenophobia that has flared as the country sits at the center of Europe’s refugee crisis. Some worry that both the book and the buildings, if renovated, will become rallying points for today’s neo-Nazis.��

The debates in Germany highlight a fundamental question that many countries in the world struggle with: What do you do with symbols of a past that many people today find abhorrent?

In the United States, fights over the display of the Confederate flag in public places surface almost weekly. Ukraine is systematically removing statues of Vladimir Lenin and other totems of the country’s Soviet past. In Spain, where authorities in Madrid are renaming streets that commemorate Francisco Franco, divisions simmer over demands to remove the late dictator’s body from the vast monument named�� Valley of the Fallen that glorifies his reign.

The Rising Sun flag – a controversial symbol of Japan’s imperial history – is still used by the country’s Maritime Self-Defense Force, much to the anger of Japan’s neighbors. Britain has been embroiled in a controversy over whether to remove a statue of Cecil Rhodes – for whom the prestigious Rhodes scholarship is named – from a college at Oxford University because of critics’ concerns about his ties to Southern Africa’s colonial and racist past. The university says it will stay right where it is.

Yet in few places do historical symbols evoke more sensitivity than in Germany.��

One reason is the sheer scale of the atrocities committed during Hitler’s reign, which is why Germany banned the swastika and other Nazi iconography right after World War II. But the republishing of “Mein Kampf” and the possibility of refurbishing Zeppelin Field signal what may be a new willingness among many Germans to confront the country’s dark past, in ways that would have been considered unthinkable just a decade ago.��

“The connection between the two is that we don’t hide any buildings, and we don’t hide any books,” says Alexander Schmidt, a historian at the documentation center of the Nazi Party rally grounds. “We can’t hide history.”

When Cornelia Kirchner-Feyerabend, a high school history teacher, was growing up in Nuremberg, the rally grounds were hidden. Not physically – for their size, more than four square miles in total, made that impossible. The site includes the semicircular Congress Hall, the largest remaining National Socialist structure in Germany, and the Great Road that gives a view of Nuremberg castle, a symbol of Hitler’s expansionary aims.

It was more that schools didn’t organize trips to the site. Nor did Ms. Kirchner-Feyerabend, as a youngster, ever go to a concentration camp. Visiting both is obligatory now.

In the aftermath of World War II, history was shrouded in silence. It wasn’t until the 1960s, during the trials of 22 SS men for their crimes at Auschwitz in Frankfurt, that many young Germans learned about the crimes of their parents – turning the protests of that turbulent era into ones specifically directed at Nazi collaboration and impunity. Kirchner-Feyerabend, a history buff in a suit and pearls, says she doesn’t know what her own father, a soldier in Russia, did during the war. “You can’t imagine how many times I’ve regretted I never asked,” she says.

In fact, like so many of her generation, she says she learned the most about her country’s history watching the 1978 award-winning American TV miniseries “Holocaust,” featuring Meryl Streep.

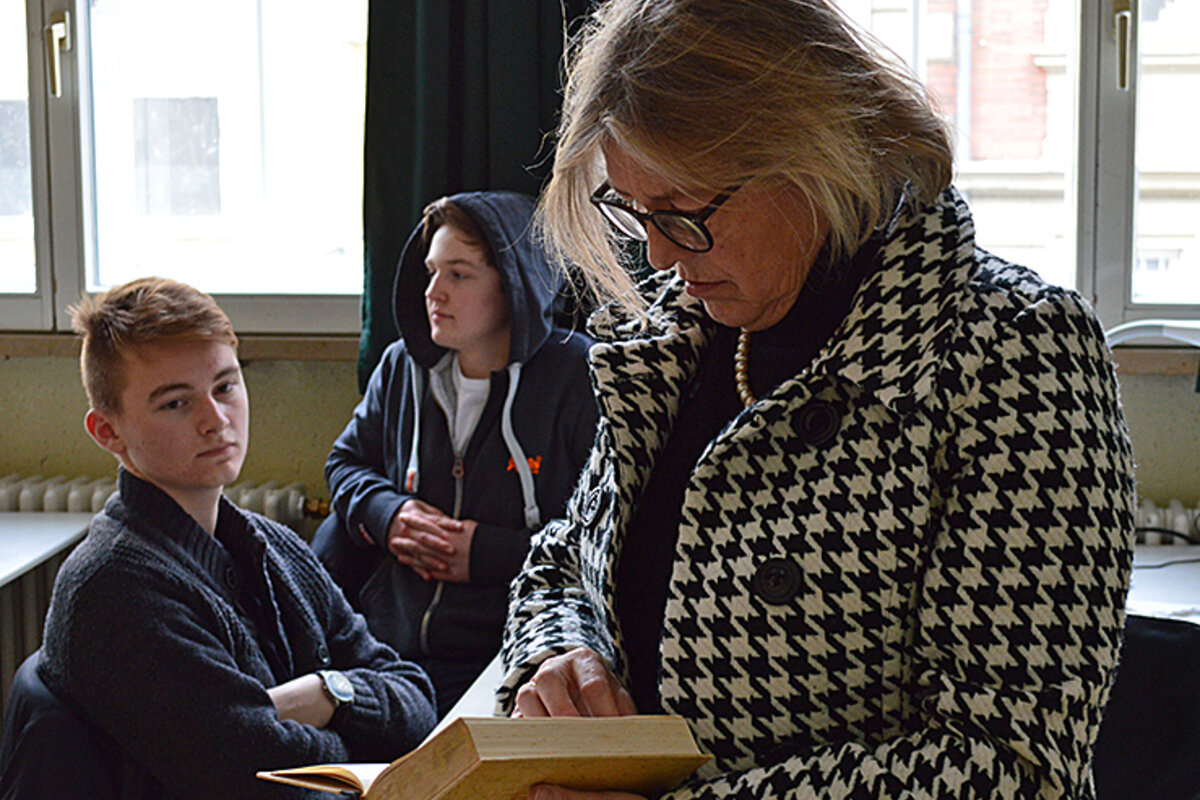

On a recent day at her public high school, the oldest one in Germany, she leafs through an antique edition of “Mein Kampf” that one of her students brought in. It was his great uncle’s and, inside, the dedication signed by the mayor of Munich reads: “For the newlywed couple with best wishes for a happy marriage.”

Her own history teacher, she says, would not have dared to bring the book into the classroom. He was not an “Old Nazi,” she says, but for everyone at the time, Hitler’s text was treated as something to be locked in the “poison cabinet.” In fact, here in Bavaria, where Hitler rose to power and where his last address was listed, the Americans handed the state the copyright of “Mein Kampf” after the war. Bavaria promptly banned its republication; the ban expired on Jan. 1 of this year.

A new, annotated version by a Bavarian research institute was released Jan. 8. Even though it is 2,000 pages long, it has sold out, showing the interest in an edition that dissects the book. Kirchner-Feyerabend’s school, Melanchthon, an imposing sandstone structure with a red-tile roof, is on a waiting list.

The book has stirred criticism, especially from some Jewish groups. They are worried about a rise of religious intolerance, both from old anti-Semites and by newer disaffected Muslim immigrants in Europe. But in a telling sign, the main teachers union in Berlin called for it to be introduced in classrooms.

“Nowadays, too many countries are affected by political extremism associated with propaganda and slogans, and excerpts from the annotated edition of ‘Mein Kampf’ can show young people how speech and text can lead to disaster,” says Josef Kraus, head of the teachers union GTA.

“I believe that 70 years after the end of World War II, German society has become more sovereign and more mature. We finally have the opportunity to crush both the myth of Hitler and that of ‘Mein Kampf,’ ” he says.

The students in Kirchner-Feyerabend’s class are like any group of high-schoolers. They’re dressed in the standard teenage uniform – jeans and hooded sweatshirts. They frequently goof off. She asks them to quiet down, on more than one occasion. The students don’t feel the heaviness of Germany’s past the way their parents, and especially their grandparents, do.��

Their views on what to do with the Nazi Party rally grounds reflect the divisions in society, but they all believe it’s nothing to be afraid of. For them, studying “Mein Kampf” as a primary educational source is natural. Many fail to understand Hitler’s appeal in the 1930s, seeing him as “ridiculous” or “insane.” During class, they talk about a movie some have recently seen, “Look Who’s Back,” a bestselling satire recently adapted for the screen about Hitler returning to Germany in modern times but with no knowledge of what transpired after 1945.

Alex Wekerle, a student in a red sweatshirt in the back row, says that his grandmother, who participated in the Nazi Party’s young people’s movement, Hitler Youth, wouldn’t be able to view the past through satire. And yet, young Germans still feel what is called here a “special responsibility,” and often reflexively disassociate themselves from the period.��

The student who brought in his great uncle’s issue of “Mein Kampf,” Johannes Jung, immediately prefaced it by clarifying that his uncle wasn’t a Nazi. Coping with the past, or �ձ�������Բ���Գ�ٲ������ä���پ����ܲԲ�, still plays a central role in German society. It undergirds the country’s pacifist foreign policy, its close relationship with Israel, and its fears of the far right generally.��

The refugee crisis, which Germany has been at the center of, has inspired violence; brought out an angry display of xenophobia with Pegida, the anti-Muslim movement; and boosted the right-wing political party Alternative for Germany. But many people also see German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s acceptance of refugees as a noble position formed by, among other impulses, a desire to be “good.” Often the weight of the past is blamed for naiveté or extreme political correctness on the part of the government. This includes claims that Berlin underplays the problems caused by foreigners – exemplified, most recently, by the sexual assaults on women in Cologne on New Year’s Eve – so as not to stoke the far right any further. Many outsiders say it is time for Germany to play a bigger role militarily in Europe, to get over its fears of the moral ambiguities of conflict.

• �� �� • �� �� •

if you ask the students in the animated classrooms and bustling hallways at Melanchthon whether a 70-year ban on “Mein Kampf” was excessive, they’ll say it wasn’t. For starters, a collective national response to such a sensitive topic could never have happened before reunification in 1990. Prior to that, the nation was divided over the legacy of the Nazis, with communist eastern Germany perpetuating the fallacy that it was West Germans alone who backed fascism.

Students also say that it wasn’t until 2006 – just a decade ago – that Germans raised the national flag without inhibition. Germany hosted the World Cup that year, and suddenly, in the heady drama of the soccer competition, a new German patriotism took root. Still, they say flags are taboo enough that they would only wave them at a game.

One other sign that German attitudes about the past are changing is a theater production now traveling the country. Created by the company Rimini Protokoll, the play, “Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf, Vol. 1 & 2,” explores the myths surrounding Hitler’s manifesto. The production has been sold out at every stop.

Relying on documentary theater, the Berlin-based group traveled around Germany to talk to some 50 people about their history and experiences with taboos surrounding the book.��

“This text has come along with a myth in Germany that it’s infectious, that if someone reads it he could convert into some kind of radical [right-winger] or anti-Semite or racist,” says Daniel Wetzel, one of the artists who leads the theater group. “With the process of the book becoming available to everyone, there is a kind of adjustment in thinking.”

A shift in attitudes is taking place over the Nazi Party rally grounds, too. Amid the shortages and destruction that existed after the war – nearly all of Nuremberg’s medieval old town was bombed – the grounds had to be reused. Former SS Barracks housed the US Army. The Great Road was used as a runway for the US Air Force. For decades, the space was occupied but the history of it ignored. Authorities tried to rename Congress Hall, but the new name never caught on, so it went back to Hitler’s original name for it.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that the first information exhibit was erected. The documentation center didn’t open until 2001. Today, some 250,000 Germans and foreigners visit these grounds each year. In fact, a city that always preferred to emphasize its imperial history now understands that its Nazi legacy is just as big of a tourist draw. Stephen Brockmann, author of “Nuremberg: The Imaginary Capital,” attributes that to a new “sense of normalization and responsibility.”

Old Nazi architecture, of course, exists everywhere in Germany. Some of it, like Zeppelin Field, is listed on a federal registry and cannot be bulldozed. Most often it has been repurposed. Federal ministries sit in old Nazi buildings; soccer teams play in their stadiums. On the island of Ruegen, an abandoned resort called Prora, built between 1936 and 1939 as part of the Nazi’s Strength Through Joy project, is being redeveloped into a tourist destination – unapologetically. Developers say 85 percent of the condos and apartments, to be completed in 2017, have been sold.

“We live in the here and now,” says Iris Hegerich, a managing director of Irisgerd, a property firm whose development of condos and vacation rentals there is called New Prora. “The German population can’t change the past.”

• �� �� • �� �� •��

Preserving the Nazi Party rally grounds has in some ways been a less controversial project because it’s not being done for overt commercial gain. Yet the size and scale of the undertaking has brought it national scrutiny – and at least some criticism. First, initial estimates put the cost of the renovation at €60 million to €75 million. The plan is not to restore the buildings to how they looked prior to the war, at the apogee of Hitler’s power. It is to maintain them in their current, half-ruined state. In short, authorities want to do the absolute minimum so that the ruins can be handed on to the next generation. “Maybe in 100 years they’ll decide they don’t need [the grounds],” says Mr. Schmidt, the historian at the documentation center.

This is a critical year. Once the exact cost of the renovation is determined, the city will ask the state and federal government for financial backing. It’s too expensive for the city to undertake alone. Plus, the longer the wait, the more costly the renovation will be.

Looking out at Zeppelin Field from a window in the documentation center, Schmidt acknowledges that this is not a straightforward preservation project, like earmarking money for restoring a school or church.��

“It is not so easy to know what is right,” he says. “We know this is not a nice building. It is not connected to good history, only bad history.”

But, he says, if authorities allow Zeppelin Field to disintegrate, they run the risk of turning the grounds into a potent symbol, as he argues the prohibition of republishing “Mein Kampf” did. And, without refurbishment, the entire area will be closed off to those who use the space today for everything from car races to cycling. It would take away a piece of land that served as a recreational area well before the Nazis came to power.

Yet others believe the only way Nuremberg can move forward is by letting go of the past, not preserving it. Zurich-based architect Willi Egli, who also chairs the advisory council on architecture in Nuremberg, believes the grounds should be allowed to crumble naturally, even if that entails fencing it off.

“Without spending millions, the Zeppelin Field is destined to die anyway, and, in all clarity, it should be allowed to do so,” he says. “Germany shouldn’t look backwards anymore. It should rather bring into the future its enormous, sophisticated vitality.”

Others say that preserving Zeppelin Field is the progressive way forward, part of the continuum of Germany dealing with its dark history. Postwar silence eventually gave way to truth seeking, but the emphasis at first centered on the Nazi leaders of the time. Historians then began to probe German institutions that allowed the Holocaust to happen. Then they started to cope with the idea that ordinary Germans enabled the tragedy to happen – some directly, some with willful blindness.

The evolution of thought is reflected in monuments, too, from the opening of concentration camps to the public to erecting memorials to the dead. The Nazi rally grounds represent one more step.

“This is not a memorial of victims; it is the other side, a memorial of bystanders,” says Schmidt.

He notes that, standing at Hitler’s rostrum, feeling the dimensions of the space and the intentions of what the Führer had for the future, visitors are prompted to ask themselves a central question: “Perhaps if I had lived in Nazi times, what would I have done, if I stood in Zeppelin Field? That is the question we should be asking ourselves, so that we aren’t bystanders again.”

Correspondent Daniel Mosseri��contributed to this report from Berlin.

��