For Mexico's migrant workers, a push for cross-border justice

Loading...

| Guanajuato State, Mexico

This article was designed to be read on the Monitor's long-form platform.

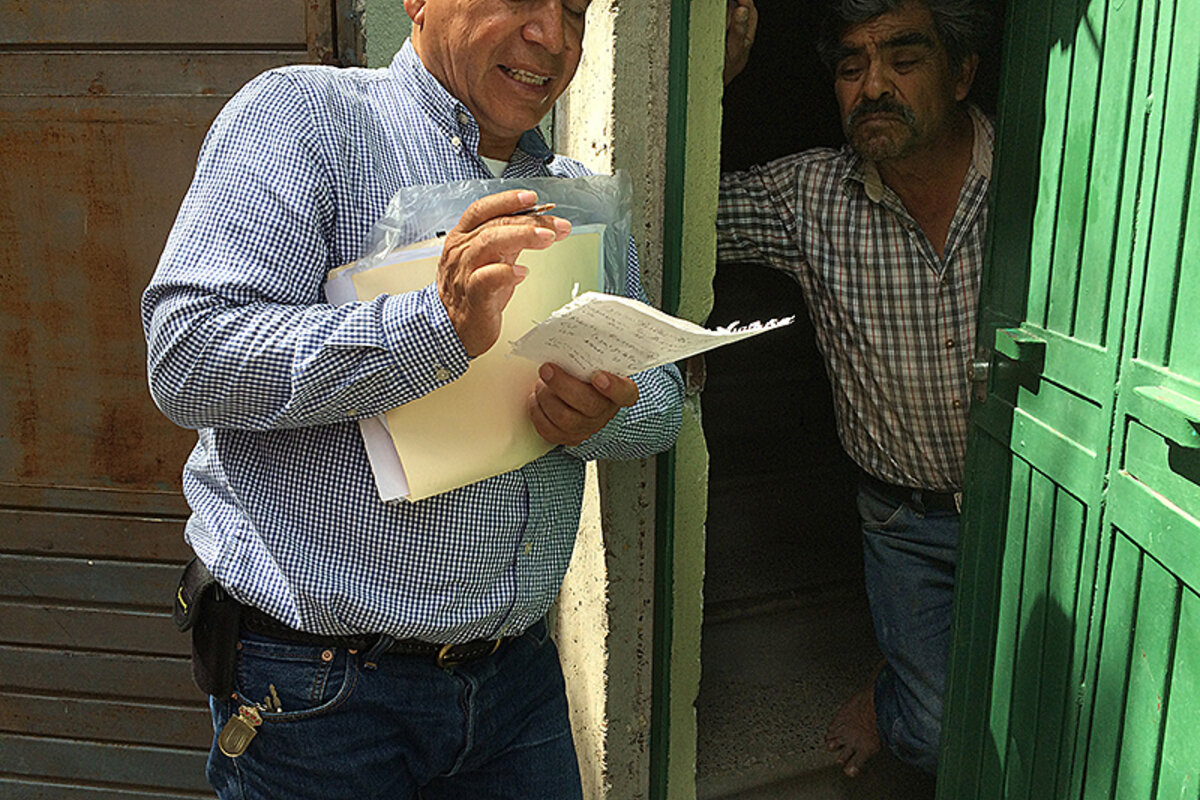

Miguel has been in this small, hillside town in central Mexico for no more than 30 seconds before he focuses in on his first target: a heavy-set man sweeping the floor of an upholstery shop.

He crosses the main road to ask the shopkeeper if he’s heard of two men that supposedly live here and spent time picking vegetables in the United States. They’re eligible to join a lawsuit and possibly receive thousands of dollars for their unpaid work.

The upholsterer says no, but points Miguel down the road to a paper-goods store.

It’s the beginning of a game of neighborhood hot-potato, where Miguel, a US-trained lawyer who now works with return migrant laborers, is passed from one shop owner to another. By the time he arrives at a hardware store on the edge of town, he’s left wondering if people here truly don’t know these two men, or if they’re just too scared to talk.

Every hunt for justice has to start somewhere.

“Sometimes I feel like an ant trying to strangle an elephant,” says Miguel, whose last name is withheld due to security concerns. “But I think that the more people that do this, that try to help, the bigger difference we could make.”

On Miguel’s car console balances a pile of double-sided papers listing scores of names of migrant workers who picked onions and cucumbers in the US on temporary visas between 2012 and 2014 and had big chunks of their wages withheld.

For decades, foreign workers have traveled to the US on guest worker visas to help pick fruit and vegetables, cut lawns, work in restaurants, and set up carnivals. Workers from Mexico make up the large majority of visa holders for these low-skill categories of guest laborers.

Migrant workers say they expected the visa process to protect them from exploitation. But the way the system is designed can make many workers vulnerable to exploitation and trafficking. Temporary workers are bound to one employer, and often arrive in the US in debt due to illegal recruitment fees or upfront transit costs.

Advocates say abuses that can add up to trafficking – lying about the nature of the work before arrival, forcing employees to work long hours without breaks, making threats about worker’s families, paying workers below the minimum wage, and physical or sexual assault – are exacerbated by the fact that guest workers are required to leave the United States at the end of each season. Back home, they are far away from the US legal system or advocates that might help them push for justice against abusive or exploitive employers.

But over the past decade more lawyers like Miguel, NGOs, government representatives, and migrant advocates on both sides of the border have worked together to short circuit a guest-worker system that relies on laborers not knowing that they are entitled to legal recourse, or how to go about getting it. They see this effort for cross-border justice, painstaking and time-consuming as it is, as vital to reducing labor trafficking and migrant worker exploitation in the US.

“The message needs to be clear to US employers that workers aren’t disposable. If you don’t have people working in the country of origin to empower workers to access justice at home, [US] employers assume they can send them home and silence them,” says Cathleen Caron, executive director of the Global Workers Justice Alliance, which provides “portable justice” to migrant laborers in Mexico and Central America through a network of local advocates. “The reality is the workers’ lives are in two countries, so our solutions have to be in both countries, too.”

‘I’ve never heard of them’

After six hours, Miguel encounters a glimmer of hope.

A group of neighbors gathered outside the lone bodega along a dusty, back road say yes, they’ve heard of a pair of brothers. In fact, that’s the boys’ father driving by right now.

Miguel hops back into his car. He crosses a set of railroad tracks and passes a two-story kiln billowing with black smoke.

He pulls over and approaches the man believed to be the father, introducing himself and explaining why he’s there. Before Miguel can finish, the man says briskly, “I’ve never heard of them.” The conversation is over.

“People get scared. They think the US is one big guy with connections to everything, like God,” Miguel says later. “Their fear is very real, even if it seems irrational.”

Over the past seven years, Miguel has worked on scores of cases, finding hundreds of workers who have suffered from abuses ranging from withheld wages to modern day slavery. While days like this, where he can’t seem to catch a break, are common, he also has a long list of successes – like the time he found 20 workers in three hours, or the days when he gets to tell workers that they’ll be receiving money from a settlement.

But even when delivering positive news, Miguel’s role as a foot soldier in these legal battles is replete with frightened workers.

Once he visited a town in southern Mexico on a case that had already settled. Many of the people he found didn’t want to accept the thousands of dollars awarded to them: They feared they would be blacklisted by recruiters or that the US government wouldn’t issue them future work visas.

Francisco used to share that anxiety.

He had worked for a landscaping company in Dallas for eight years when he learned he was owed thousands of dollars for travel expenses – which most years put him into debt before he even arrived – that should have been covered by his employer.

When a paralegal with the advocacy group Centro de los Derechos del Migrante (CDM) traveled to his rural town in 2013, he told her he wouldn’t join the case. “I was too afraid. My family would have nothing,” if the company retaliated by not asking him back, he says.

A year later, the company changed ownership, and the paralegal contacted Francisco again. He no longer felt his job was at risk and joined the suit. He was awarded more than $2,000, which is helping him build a home for his wife and five children. Even more, he says it’s changed the way he thinks about the position of guest workers in the US.

“I learned more about my rights,” Francisco says, noting that his former employers often used scare tactics – like threatening to send people home or dock their pay. Other employees reported being forced to go to the bathroom in disposable bags so they didn’t waste company time. Now, he says, when he goes to work in the US, he carries phone numbers of people he can call for help or share with other workers if something doesn’t seem right.

“I have more confidence,” he says. “I feel like there was some justice.”

It’s critical to hold employers accountable for their actions, but educating workers about their rights is also integral to curbing modern day slavery, says Staci Jonas, a managing attorney of the human trafficking team at Texas Rio Grande Legal Aid.

And the more who stand up, the better.

“Each plaintiff that can overcome this cloud of fear and intimidation [to ask for legal recourse] is more powerful and makes a case more powerful,” says Andrea Ortega, the director of the migrant farm worker unit at Florida Rural Legal Services. “If you have just two to three plaintiffs that sign on to a case, an employer would rather pay them off and continue doing what they’re doing, because they’re making profit.”

And though pursuing cases like unpaid overtime may seem like small beans, the Urban Institute found that trafficking victims frequently suffer other civil and criminal abuses.

“My feeling is that if you combat wage theft, you are also combating trafficking,” says Martina Vandenberg, the founder and president of the Human Trafficking Pro Bono Legal Center in Washington. “You really need to combat all forms of exploitation, and then you will also capture the more heinous abuses on the spectrum.”

Some trafficking cases are identified through these more “routine” inquiries.

A current civil case in Florida was discovered when a Honduran strawberry picker called a legal services group about worker’s compensation after he was injured on the job. It turned out that he and 50 others had been duped into selling property and taking out high interest loans to pay up to $4,000 apiece to work on what they were told would be a well-compensated, long-term gig. When it became clear that wasn’t the case and workers wanted their money back, they say the recruiter threatened to kill them – and their families back in Honduras.

“For decades attorneys have seen these kinds of abuses against workers,” says Ms. Jonas. “What’s changed in recent years is the realization that this is more than just a wage violation or a human rights complaint. It’s something that there’s a name for: modern day slavery.”

It’s 1:30 a.m. Time for work.

Growth in the guest worker visa programs, which has been accompanied by a rise in abuses over the past several decades, has fed the need for more legal assistance.

Although the total number of trafficking cases investigated by federal agencies went up between 2012 and 2013, only 25 labor trafficking cases were prosecuted in 2013, according to the State Department’s Trafficking in Persons report. Ms. Vandenberg says this is in part due to the fact that labor trafficking cases are often harder to prosecute than sex trafficking cases.

Despite the challenges of bringing criminal charges at the federal level, since 2008, more tools have become available to lawyers to litigate trafficking cases. That includes special visas that allow victims of trafficking or serious crimes to remain in – or return to – the US after their work visas expire.

One cross-border case that relied on these tools involved seven Mexican workers at a seafood plant in Louisiana.

Martha Uvalle, one of the workers, first came from the Mexican state of Tamaulipas to boil and peel crawfish in 2006 and was asked back every year by her employer. But work conditions started to worsen. By 2011, hours shifted from eight-hour days, to 1:30 am wake-up calls and shifts that could last between 16- and 24-hours. The plant doors were sometimes blocked to keep workers from leaving to use the restroom or take a break.

Her boss heard rumors that workers were thinking about calling the police. “At one point he told us, ‘There are good people and there are bad people in the world,’ ” says Uvalle. “And that he knew where our families lived.”

A colleague called labor activists, who helped Uvalle and other workers set up a meeting with their boss to ask him to improve working conditions. When their requests were declined, they decided to pursue legal action. Uvalle and three others remained in the US while the investigation was under way, while three other workers returned home to Mexico.

The company ultimately was fined more than $34,000 for safety violations and was ordered to pay more than $200,000 for violations of wage and hour rules. Uvalle and her peers who stayed in the US applied for and were issued special visas that allowed them to remain in the states after their work visas expired.

But for the three workers that chose to return to Mexico, things didn’t move as quickly.

‘FedEx doesn’t go to these places’

There’s no case without a worker’s voice, says Greg Schell, the managing attorney at the Migrant Farmworker Justice Project in Florida.

“[Guest worker] conditions can only change with carefully planned and executed lawsuits. And we need workers’ voices to do that,” says Mr. Schell. “They are more than pawns in this deal. They need to be involved in the solution.”

Done right, cases can have a long-term impact. Take one he worked on in 2002 with Mexican guest workers that established that all agriculture employers have to reimburse visa and transportation costs within the first week of work. The ruling – later expanded to include nonagriculture workers – cuts down on scenarios where workers are in debt when they arrive, which puts them at greater risk of trafficking or exploitation on the job, according to by the US Government Accountability Office.

But the “glacial pace” of the US justice system can be hard on workers, he and others say.

“Navigating the transnational web [of justice] is extremely frustrating prior to, during, and even after a case,” says Ms. Ortega. Many migrants don’t have cell phone service in their small hometowns, and often there’s just one landline shared by an entire community. “Even when I talk to a client, we can’t necessarily get paperwork to them,” she says. “FedEx doesn’t go to these places” where an address might read, “small house on a hill behind the church.”

Recently, Ortega hired an advocate from the Global Workers Justice Alliance to help her locate a client in Oaxaca. Without his signature, his case couldn’t move forward. The advocate, Maribel, drove into a dangerous and politically unstable part of the state, parked her car, and walked for nearly two hours to reach the client.

It seems like a lot of time for just one person’s signature, but Maribel, whose last name was withheld due to security concerns, says she doesn’t see it that way. “This is a chance for someone to have his or her rights as a worker and as a migrant recognized.”