Vowing to bulldoze corruption, Tanzania's president bulldozes dissent

Loading...

| Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

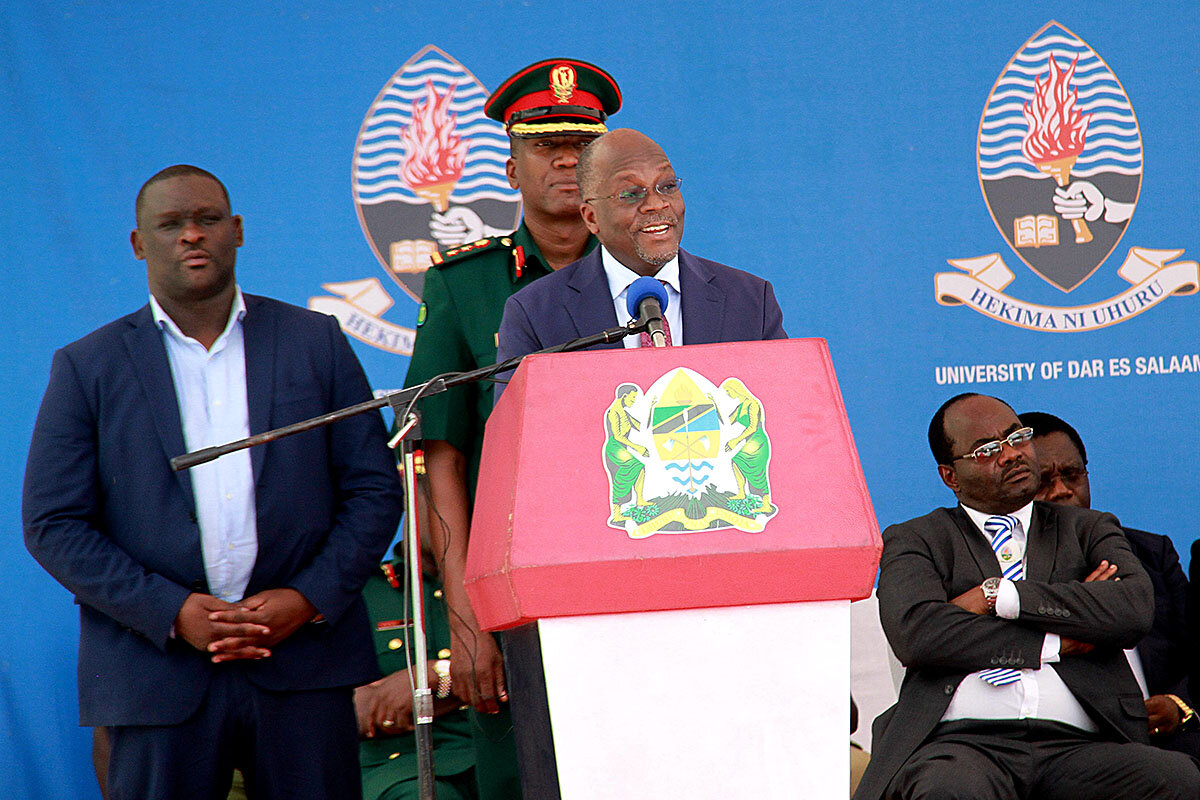

On a December day three years ago, two months after he was elected president of Tanzania, John Magufuli walked out of the presidential palace here and began scooping handfuls of dried leaves and torn plastic bags into a trash bin.

The symbolism of his participation in the nationwide cleanup could not have been more pointed.

Mr. Magufuli had run a campaign promising to clean up government in Tanzania, weeding out corruption and bureaucratic bloat. His supporters called him “The Bulldozer.”

Why We Wrote This

It’s a familiar pattern: Populist leaders pledging to clean up government wind up taking an authoritarian turn. In Tanzania’s case, some international donors are starting to push back.

They meant it as a compliment, and he took it as one. Magufuli, whose party, the CCM, has ruled Tanzania in various iterations since independence, quickly slashed the size of his cabinet, cut government travel spending and his own salary, and sacked the director of the largest public hospital in the country during a surprise inspection. He slashed 16,000 “ghost workers” collecting salaries from government payrolls and slapped higher taxes on international mining companies extracting the country’s precious metals.

“Magufuli has proved to be immensely popular not just because Tanzanians have suffered under the yoke of corruption for many years, but also because his actions seemed to say that he was a different kind of leader — someone who understood that the role of the president was to make sacrifices for the people rather than the other way around,” writes Nic Cheeseman, a political scientist at the University of Birmingham, .

His brash efficiency has also taken a darker turn. His administration has passed a succession of laws that it routinely uses to harass and arrest journalists, activists, and critics. Opposition political gatherings have been banned. His bold proclamations on the economy have spooked investors. And his statements against pregnant teenagers, members of the LGBT community, and users of birth control have frustrated Western donors – some to the point of cancelling aid to the country.

But if the president’s authoritarian pivot surprised some, many observers say his efficiency and silencing of those he disagrees with are two sides of the same coin, part of a strategy of governing that delivers results in return for quiet allegiance.

“Magufuli’s crusades have always been personal; he doesn’t feel the need to work within the framework of the law or within institutions,” says Dewa Mavhinga, the southern Africa director for Human Rights Watch. “And that has created many of the problems we’re now seeing.”

'Watch it'

For many Tanzanians the chill under Magufuli’s administration descended slowly, like a changing of seasons. In the first two years of his presidency, as his cleanup projects in government dominated the headlines, his administration began developing legislation that fenced in the activities of local media and research organizations. One law slapped a $930 registration fee on news websites and bloggers, forcing many to shut down. Another threatened anyone who disagreed with official government statistics with jail time or a hefty fine.

“Media owners, let me tell you: Be careful. Watch it. If you think you have that kind of freedom – not to that extent,” he warned last year.

When protestors against the president held a rally in June 2016, police broke it up with tear gas, and then banned all opposition demonstrations until the 2020 elections.

“The government has made clear that it wants civil society to be quiet, to stay in line,” says Mchereli Machumbana, a human rights activist. “The civic space is shrinking all the time.” (Several other activists in Tanzania interviewed for this story asked not to be quoted out of concern it could jeopardize their work.)

Meanwhile, in a kind of society-wide echo of his campaigns to clean up government, the president began pushing a moral agenda. He promised that teenage girls who became pregnant would never be allowed to return to school () and said that of LGBT rights. Women who used birth control he said at a rally reportedly attended by a representative of the UN Population Fund, and so was.

The comment on birth control, like many of the president’s other statements, did not provoke an immediate change of policy. But they helped create a climate of deep fear among many groups. In October the commissioner of the Dar es Salaam region, Paul Makonda, encouraged citizens to report LGBT individuals so that a government task force could round them up. Magufuli’s government distanced itself from the remarks, but many observers point to a rise in anti-LGBT rhetoric during his presidency. Ten men were arrested on the island of Zanzibar, and untold numbers disappeared into hiding. (Gay sex is illegal in Tanzania, but the law has been rarely enforced.)

Pocketbook pushback

Many of Magufuli’s proclamations on morality seem crafted to assert Tanzania’s independence from the Western governments and institutions that provide it aid, says Mr. Mavhinga of Human Rights Watch. The country is the third-largest aid recipient in sub-Saharan Africa and has long been a darling of donors.

Those same donors have begun pushing back. On Nov. 13, the World Bank withdrew a $300 million education loan over the prohibition on pregnant girls returning to school (an old rule, but one the president vowed to protect),

A few days later, however, the Bank announced that it would after Tanzania’s government agreed to make a provision for pregnant girls’ education.

China, meanwhile, has become another major aid player in Africa, including Tanzania, and may help cushion the government against disapproving Western critics.

“The thing that makes you happy about [Beijing’s] aid is that it is not tied to any conditions,” Magufuli said in November, . “When they decide to give you, they just give you.”

Domestic activists say they see flickering glimmers of resistance to many of Magufuli’s policies.

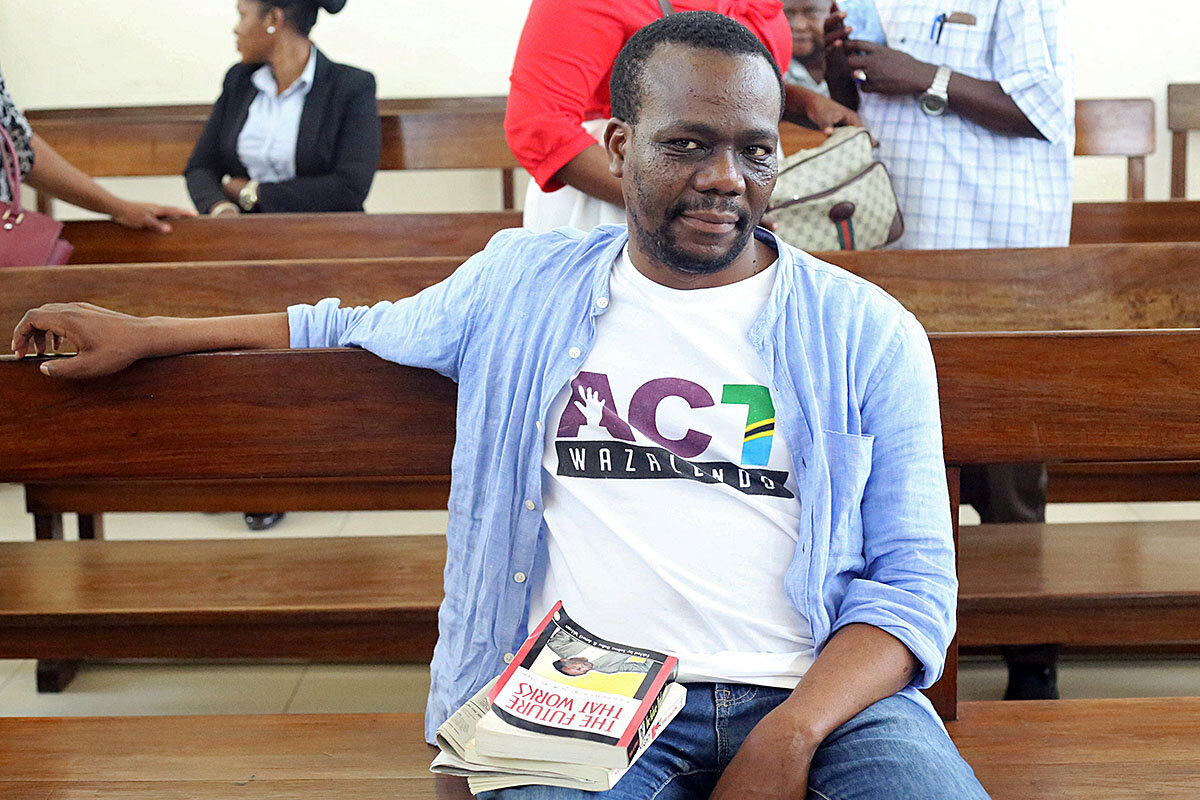

The country’s courts, for instance, have sided with several activists’ challenges against new laws, including in several cases against the founder of a popular website, Jamii Forums – sometimes compared to WikiLeaks – which the government has repeatedly attempted to shut down.

And in several denominations have used their own moral authority to challenge the president’s.

‘There is a group of people whose duty is to instill fear in people who speak the truth,” said Fredrick Shoo, the presiding bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania, . “This is wrong. Jesus was born to enable us to live in truth and not in fear.”

Shortly after his statement, by Catholic and Pentecostal leaders, the permanent secretary in Tanzania’s Department of Home Affairs warned that churches who waded into politics were breaking the law and would be deregistered.

It never happened, however, and churches continued to speak out. Other activists also refused to be bowed.

“Before I think we were sleeping on the job of protecting our democracy,” says Risha Chande, a senior communications advisor at Twaweza, a civil society organization. “We saw problems here and there, but overall the situation looked okay. Now, I think, we have really woken up.”