Biden to allies: Enduring values stand up in a changed world

Loading...

| London

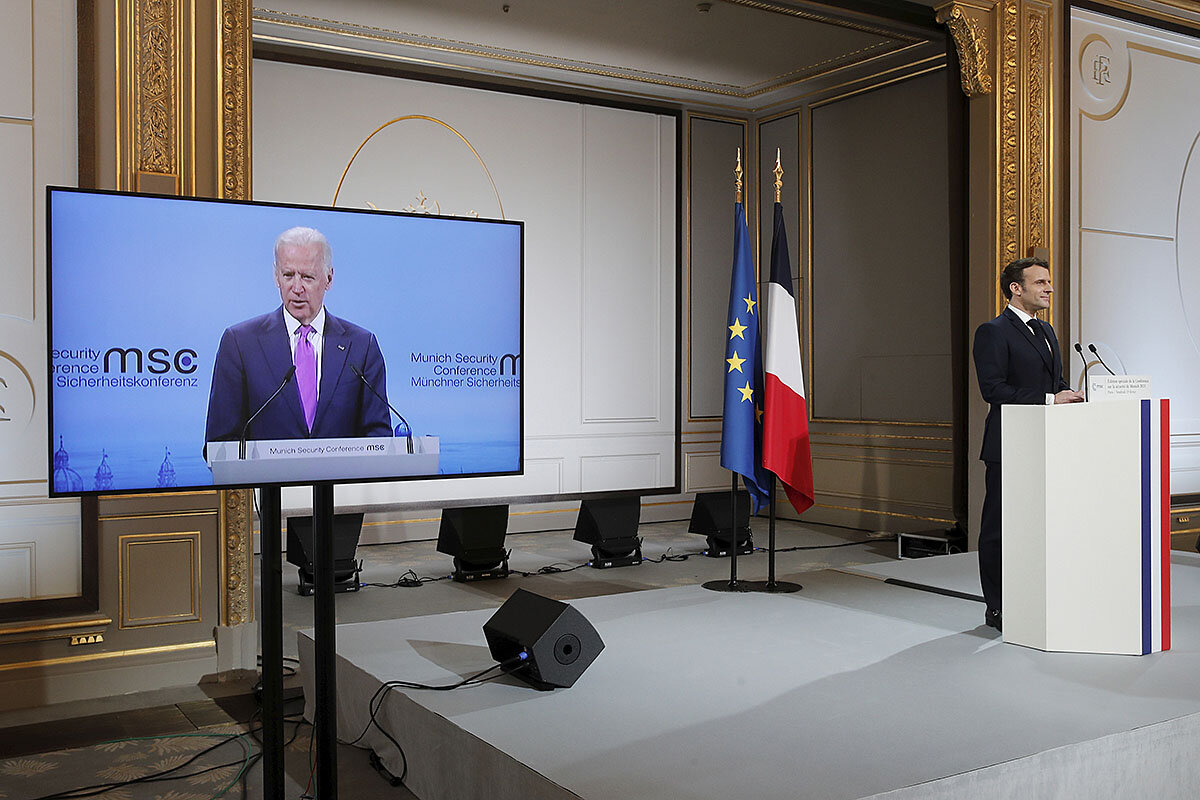

“You know me.” It’s been a refrain all across Joe Biden’s half-century in public life. And the consistency of his core policy beliefs was on full show last week, in his first foreign policy address from the Oval Office.

His remarks were delivered remotely to an annual European security meeting he’s long attended in person. And they highlighted a new challenge: applying his enduring values and priorities to a world changed beyond recognition since his last time in national office, as Barack Obama’s vice president.

Some of the changes have been building for years, above all the increasingly assertive and emboldened stance of China and Russia. Yet others are newer, and could prove even more daunting: the geopolitical after-effects of former President Donald Trump’s reshaping of America’s approach to the world.

Why We Wrote This

As President Biden tries to shape a fresh path for U.S. influence globally, he's leaning in on a message of firm commitment: to the idea that bedrock democratic values still matter, and to working with allies.

Mr. Biden’s abiding vision has been of an America leading alliances of like-minded democracies, standing strong against rivals where necessary, yet cooperating with them where possible. Those alliances, in his view, ultimately win the hearts and minds of the wider world “not by the example of their power, but the power of their example.”

All of that, he made clear to the delegates, was what he still believed in.

But beyond the challenge of China and Russia, this year’s Munich Security Conference brought to the fore doubts over bedrock assumptions of a long line of U.S. leaders: the robustness of America’s alliances; the impact of its leadership role; and, for the rest of the world, the lure of democracy itself.

China and Russia, to be sure, pose tests for the new president.

A different world

When Mr. Biden spoke in Munich a dozen years ago, soon after he and President Obama had taken office, his focus was mostly on broad international challenges that read like today’s headlines: world economic crisis; climate change; cybersecurity; Iran’s nuclear program. Even the shared challenge of fighting “endemic disease.”

But back then, he made only a glancing, largely conciliatory, reference to Russia. He didn’t mention China at all.

Appearing in Munich four years later, at the start of the Obama administration’s second term, he did cite differences with Russia. Yet he remained largely upbeat about cooperation. He spoke about China, too. But again – citing talks with the man who would become China’s leader, Xi Jinping – he voiced optimism that “healthy competition from a growing, emerging China” would prove positive, and that the U.S. and China weren’t destined to be “enemies.”

Unsurprisingly, his tone toward both rivals at last week’s conference was far tougher. He still stressed the importance of seeking cooperation, citing a range of issues where he felt it was simply essential: the COVID-19 pandemic, arms control, climate change.

But referring to Russia’s leader only by his last name, he accused Putin of seeking to weaken democratic alliances, “bully” other states, and hack into vital European and U.S. computer networks.

On China, he said it was essential to “push back” against its “economic abuses and coercion,” and shape new rules for future technology to ensure it is used to “lift people up” rather than “pin them down.”

Yet that brought Mr. Biden back to his yearslong belief in the core importance of America’s democratic alliances. Now more than ever, he said, the U.S. needed to “work in lockstep” with them.

It was on that issue that Munich highlighted what may prove his trickiest diplomatic challenge.

A different United States

Despite the welcome for his overall message that “America is back,” there were signs of continuing tremors from Mr. Trump’s downgrading of alliances in favor of bilateral “America first” dealings with individual world leaders.

In their remarks to the conference, two of Europe’s most influential leaders signaled that truly rebuilding the trans-Atlantic partnership – certainly “in lockstep” – might not prove easy.

During the Trump years, both German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron publicly questioned whether Europe could still rely on America’s bedrock support. At the Munich conference, Mr. Macron did say he believed in NATO – the military alliance between the U.S. and Europe that, under President Trump, he’d pronounced no longer viable. But he reiterated a call for Europe to seek “strategic autonomy” from Washington. And Chancellor Merkel – whose country has important economic ties with both China and Russia – paired her endorsement of Mr. Biden’s emphasis on the alliance’s “shared values” with a practical caveat: “Our interests will not always converge.”

And there is a deeper source of European skepticism: over the staying power of Mr. Biden’s worldview, and whether a Trump-style nationalism might yet return in the future.

Mr. Biden was clearly aware of all this, speaking of the need “to earn back our position of trusted leadership.”

But his most emotive words were reserved for a far wider, longer-term challenge: the struggle for the very future of democratic governance against an argument being made by China, Russia, and a number of other countries that democracies simply aren’t up to the task of handling the economic, health, and security tasks of the 21st-century world. That “autocracy is the best way forward,” as Mr. Biden summed up their view.

That is wrong, Mr. Biden asserted. “I believe with every ounce of my being that democracy will and must prevail,” he told the conference.

Of all the long-held values he brought to his address, none better defines the worldview with which he has invested his presidency. Yet now his task, and clearly his hope, will be to bring America’s overseas allies along with him.