Syria and Afghanistan: the withdrawal dilemma

Loading...

| London

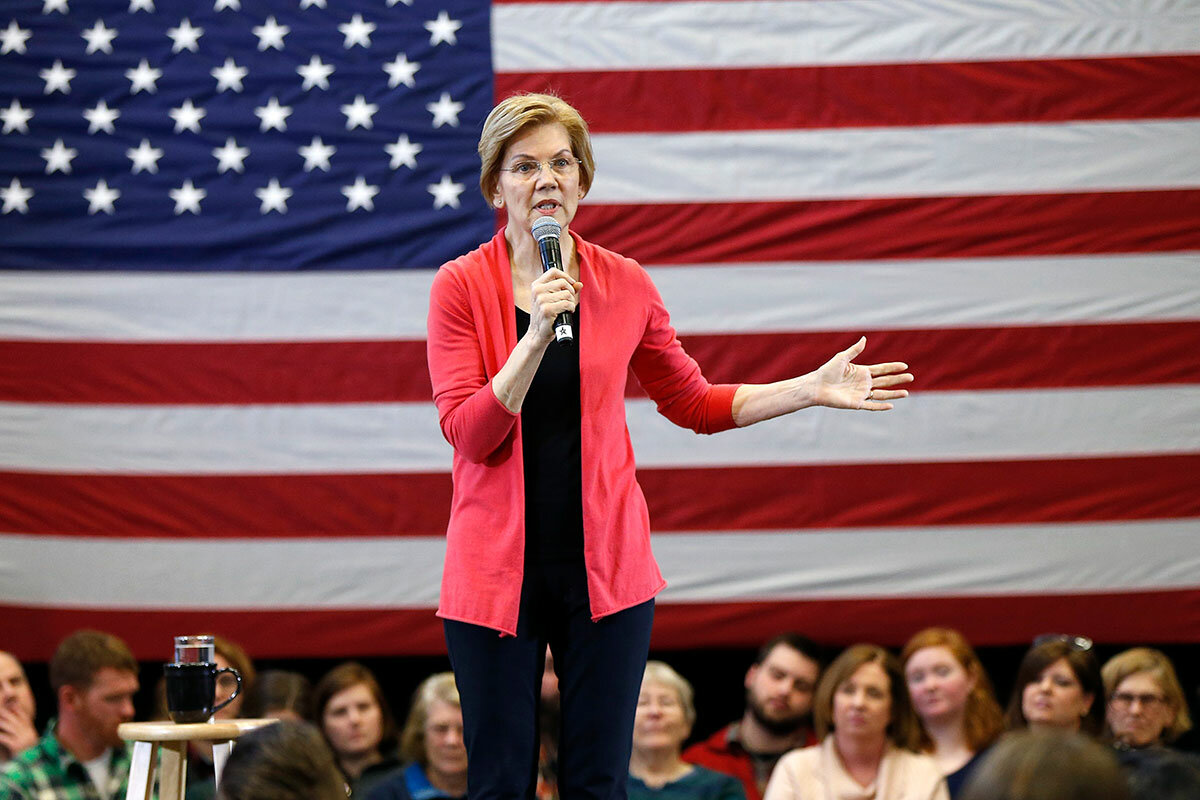

When President Trump agrees with Sen. Elizabeth Warren, the Democratic Party adversary he most likes to bait and denigrate, it’s worth taking note. Especially on an issue of real policy significance.

In this case, it’s the belief that the US military presence in both Syria and Afghanistan is wrong, and that a main reason the troops are still there is a cozy consensus among America’s defense and foreign-policy “establishment.” Mr. Trump is backing his words with action, ordering a pullout from Syria and signaling his determination to reduce troop levels in Afghanistan.

Yet with political debate likely to intensify as such pullouts proceed, it’s important to recognize that Part 2 of the Trump-Warren argument – the notion of a self-reinforcing, pro-war consensus among policy experts and professionals – is at the least an oversimplification.

Why We Wrote This

Donald Trump and Elizabeth Warren both say it: The US presence in Syria is wrong, and it’s the result of a self-reinforcing policy “establishment.” But it’s not that simple.

There was indeed broad establishment consensus on the need to contain Soviet expansion during much of the cold war. The long, failed war in Vietnam also enjoyed such support at first. As David Halberstam revealed in his seminal 1972 book “The Best and the Brightest,” that war was in some ways the creation of a coterie of academics and intellectuals around President John F. Kennedy who, in Mr. Halberstam’s phrase, crafted “brilliant policies that defied common sense.” The same has been said about the neoconservatives around President George W. Bush in the 2003 Iraq War.

Yet in part because of the failures in Vietnam and Iraq, there has also been a countercurrent of skepticism in the policy establishment in recent years.

Resisting retreat

The military brass does seem instinctively inclined to resist any notion of retreat. But retired Army Gen. H.R. McMaster, Trump’s national security adviser until April last year, wrote a seminal book as well. Called “Dereliction of Duty,” it criticized top members of the military for failing to challenge President Lyndon Johnson on his strategy as the Vietnam quagmire deepened. In the run-up to Iraq, it was Secretary of State Colin Powell, a former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who raised the central argument against the war: the challenges of a post-invasion Iraq. “You break it,” he reportedly told the president, “you own it.”

In my years covering members of the so-called policy establishment as a foreign correspondent, I found that many viewed their main role as providing what Halberstam said was missing in Vietnam: common sense.

That’s certainly true of Afghanistan and Syria. When America first intervened, after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, not just the experts but the country was in no mood to question. Eighteen years later, I don’t know a single policy-establishment figure who thinks the war is winnable. But some do raise a question a bit like the flip side of Mr. Powell’s. With the Taliban in the ascendancy, and groups like Islamic State (ISIS) and Al Qaeda there, too, what might come next if the US withdraws?

In Syria, the US has only 2,200 special-forces troops, alongside a far larger contingent of Kurdish fighters against ISIS. Russia and Iran are the dominant forces. Yet the US presence has meant they haven’t had completely free rein. Nor has Turkey, which has vowed to attack the Americans’ Kurdish allies. Some policy experts are also concerned a withdrawal would leave Israeli military action, with the risk of wider conflict, as the only counterweight to an Iranian military “land bridge” from Tehran, through Iraq, to Lebanon on the Mediterranean.

None of that means withdrawals are necessarily wrong. Senator Warren has raised a question long frustrating the policy establishment itself. She said that those in the defense establishment who kept saying “no, no, no, we can’t do that” in response to calls for withdrawals needed “to explain what they think winning in those wars looks like.”

The problem in both conflicts is that conventional victory is not on offer. The reason for the “no, no no” – or “think carefully before acting” – from some policy professionals is that in today’s world, America's main challenge is not rival armies, but militia or terror groups feeding on instability in failed or embattled states. In that context, they suggest, the question isn’t what winning looks like. It’s the potential costs to US security interests from pulling out altogether.