Why Abraham Lincoln's birthday isn't a federal holiday

Loading...

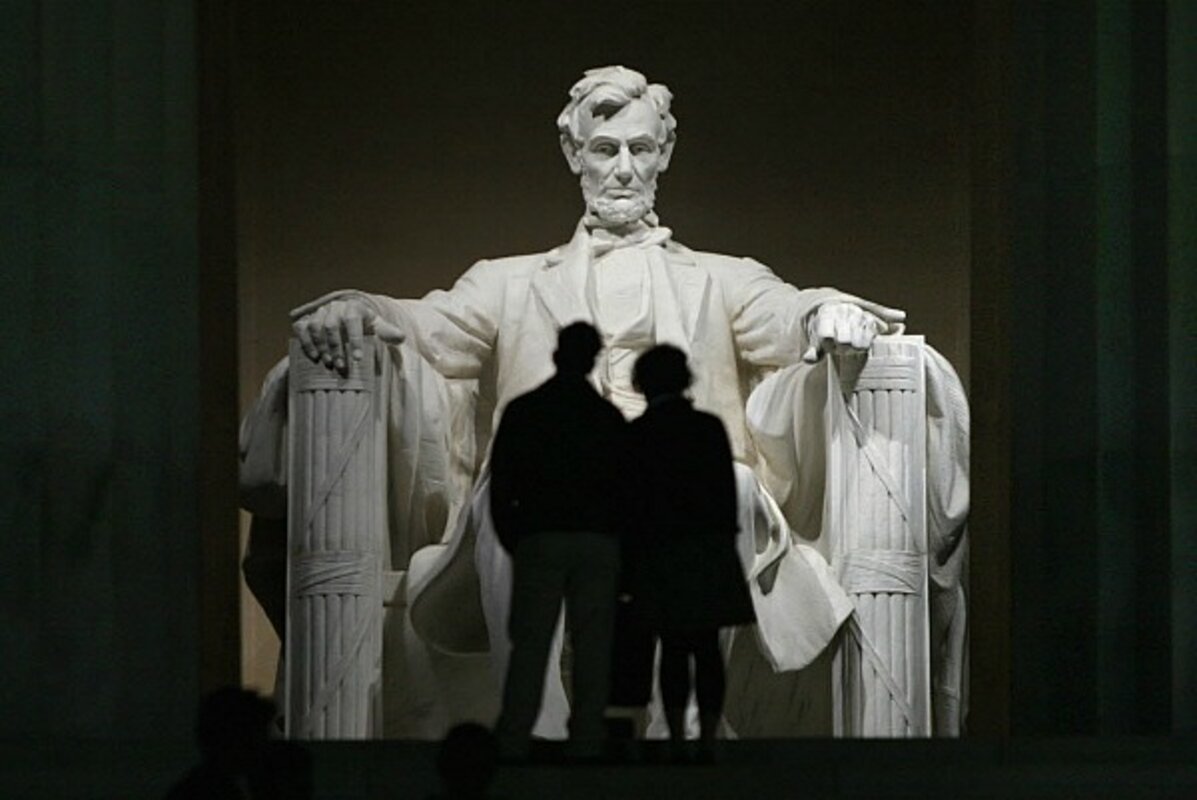

Abraham Lincoln may be the greatest of all US presidents. He ended slavery, won the Civil War, and ensured that the United States would remain united in the modern world. His face is printed on the five-dollar bill and stamped on the penny. The Lincoln Memorial is one of the nation’s iconic sites.

But Lincoln’s Birthday on Feb. 12 is not a national holiday, and it never has been. Nor is Lincoln officially remembered on a federal President’s Day in late February. That’s just not the case, despite a widespread belief to the contrary.

True, people have tried to make Lincoln’s birthday a US day of commemoration. One of the first was Julius Francis, a shopkeeper from Buffalo, N.Y. Beginning in 1874, he made the public remembrance of the 16th president his life’s mission, according to a 2003 Buffalo News article on the subject. He petitioned both Albany and Washington. New York went along and made Feb. 12 a state holiday. Washington and Congress did not.

Remember that for decades following the Civil War the South and North remained split as to how to remember its sacrifice and heroes. Days to remember the fallen arose on separate dates in the two regions. In was only with the nationalizing tragedy of World War I that these combined into the Memorial Day .

Thus, a national Lincoln holiday would have been controversial to many in the South until well into the 20th century. Perhaps that’s why Congress as a whole remained resistant.

That didn’t stop states, of course, and many state governments followed New York’s lead in establishing Lincoln’s birthday as a holiday. On Feb. 13, 2012, state offices in Illinois will be closed to honor the Great Emancipator.

But in recent years, some states have ditched Old Abe, in part because it falls near the federal holidays of Washington’s birthday and Martin Luther King Jr. Day. In 2009, the California legislature passed a bill ending Lincoln’s birthday as a paid state holiday.

Then there is the persistent legend of President’s Day – a legend formed around a nugget of truth.

In 1968, Congress considered the Uniform Monday Holidays Act, legislation that aimed to shuffle certain US holidays around so as to create three-day weekends and increased sell-a-thon opportunities.

Early drafts of this bill did include a Presidents’ Day meant to supplant the existing Washington’s birthday holiday. This name change was suggested by one of the bill’s main proponents, Rep. Robert McClory, who was – you guessed it – a Republican from Illinois.

But the bill stalled in committee. Eventually Congressman McClory dropped his Presidents’ Day proposal to mollify lawmakers from Virginia, who wanted Washington’s prerogatives preserved, according to an account of the legislation in a magazine published by the US National Archives.

Momentum was restored, and the bill passed, creating the framework of three-day federal holidays Americans enjoy today. The name of the celebration on the third Monday in February remains “Washington’s Birthday,” as is clearly stated on the .

Still don’t believe us? Check out the US Office of Personnel Management list of 2012 holidays for federal workers. It lists “Washington’s Birthday,” with an asterisk, which leads to an explanation.

“Though other institutions such as state and local governments and private businesses may use other names, it is our policy to always refer to holidays by the names designated in the law,” .

In February 2001, Rep. Roscoe Bartlett, a Maryland Republican, made a final try at raising Old Abe’s holiday profile by introducing a

This bill called for the legal public holiday known as “Washington’s Birthday” to be known by that name and no other. But it also requested that the president “issue a proclamation each year recognizing the anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln and calling upon the people of the United States to observe such anniversary with appropriate ceremonies and activities.”

This legislation was assigned to the House Committee on Government Reform, and there it languished, unpassed. Thus, 203 years after his birth in humble circumstances in rural Kentucky, Abe Lincoln still doesn’t have a federal day to call his own.