Why a Native American vet drives 1,200 miles to care for her peers

Loading...

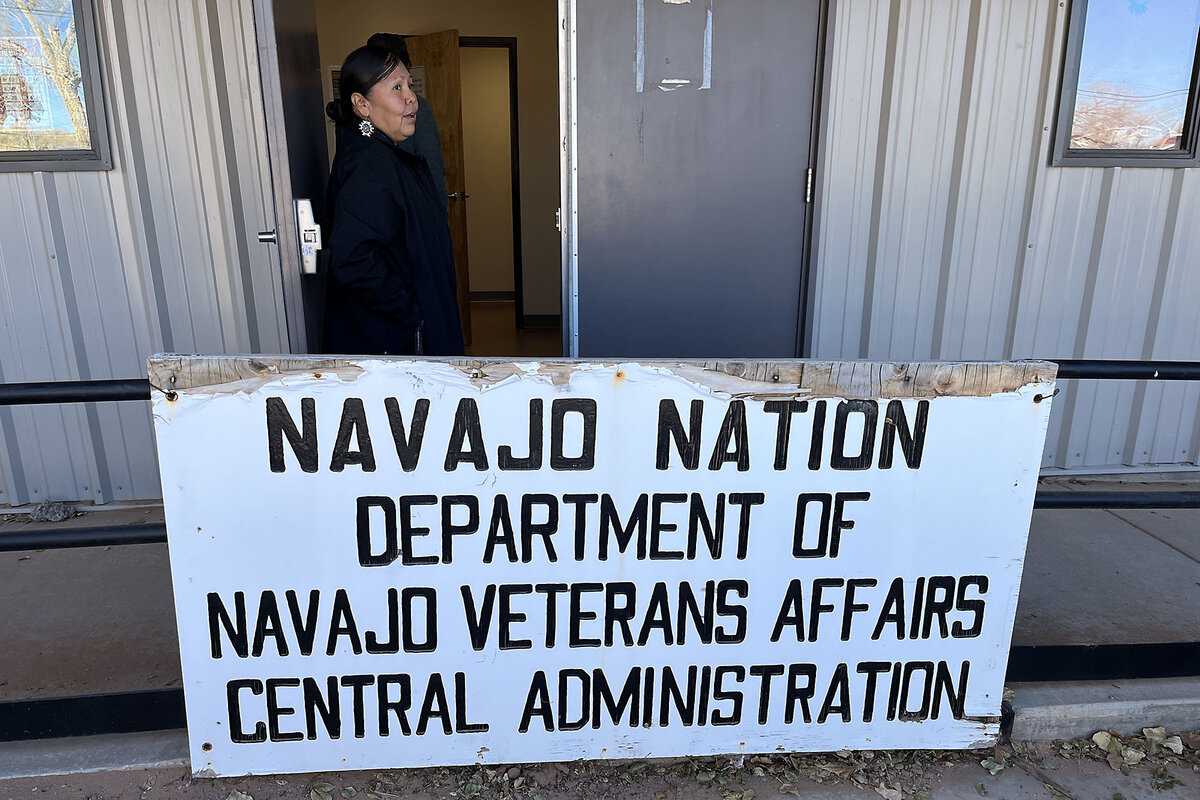

| Window Rock, Ariz.

In her work with U.S. military veterans here on the Navajo Nation, Bernadine Tyler routinely logs 1,200 miles a month driving across an area the size of West Virginia, over high windswept plains dotted with rust-red mesas.

Roughly one-third of homes here on America’s largest reservation don’t have electricity or running water, so Ms. Tyler, herself a member of the Navajo Nation and an Army veteran, brings services directly to her fellow vets, most of whom are over the age of 65.��

She points out the occasional gas station and folks walking on the dusty shoulders of pot-holed roads. There’s a bus, “but it’s very unreliable and only runs one route,” says Ms. Tyler, program lead for the Diné Naazbaa Partnership (DNP), which serves the Navajo Nation and receives funding from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.��

Why We Wrote This

Native Americans serve in the U.S. military at exceptionally high rates, yet face significant post-service challenges. Efforts are underway to better support veterans on the Navajo Nation.

“If you’re there, you’re there. If not, you’ve missed it for the day.”

For vets without transport or refrigerators, she carries bags of ice to fill the convenience store coolers that many use to chill their food and medications. She enlists volunteers, including her sons, to help haul water and chop wood for warmth in the winter.��

Though Navajo and other Native Americans serve in the U.S. military at five times the national average – a higher rate than any other demographic – they are also more likely to be unemployed, grapple with post-traumatic stress, and have lower incomes.��They are also far less likely to use, or even apply for, VA services.

The particular challenges of accessing this care came to light during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Native American veterans living in small multigenerational homes without running water on closed tribal lands died at significantly����than other former service members. The VA subsequently pledged to better serve America’s Native American community.��

In 2020, the VA created the first advisory committee for Native American veterans. It held its first meeting in 2022 and began issuing its recommendations last year. Though they aren’t binding, the suggestions of some committees have an acceptance rate of 90%, according to the agency.��

The committee’s work will be “essential,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said, “in helping us to find and to develop better and more innovative ways to serve native veterans.”��

Congressional charter recognition��

With this year’s 2024 defense spending bill, lawmakers also granted the Native American Indian Veterans a congressional charter, making it the first-ever group dedicated to the interests of Indigenous people in the U.S. to get the status. It is a development that took the NAIV nearly 20 years of lobbying to achieve. With the charter, NAIV can testify before Congress and, ideally, more easily help the VA process benefits claims.��

The hope is that these developments will not only improve care, but also foment faith that, even after decades of neglect, change is possible – particularly among the 57% of Native American veterans who say their top reason for joining the military was a desire to serve their country.��

Native American veterans are among America’s most patriotic, says Adam Pritchard, a researcher at Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families. “It’s a very important step in the right direction to acknowledge their history of the service and their ongoing needs.”��

“Our history has much mistrust,” Ms. Tyler says. Good-faith efforts to fix a long-broken system and build it up, she adds, can help heal old wounds, too.��

From code talking to broken plumbing��

In 1943, Thomas Begay joined the U.S. Marines. He was 16 or 17 years old – he’s not sure which. His grandmother delivered him at home on a snowy day in New Mexico, where his parents spoke Navajo, not English, and didn’t record the date and year of his birth.

He wanted to be an aerial gunner, Mr. Begay told the recruiter, who said, “Sure, you’re just the man that I see in the bubble shooting down the Japanese Zero,” as enemy fighter planes were called.��

The recruiter was being sarcastic, as Mr. Begay learned when he was sent to become a code talker.��While he and his fellow troops practiced the top-secret tribal language with a twist, their basic training was more ad hoc than the Marine norm.��

“They got us a rubber boat, and they just dumped us way out in the ocean and said … ‘Learn how to get to shore,’” he recalled in a 2013 discussion cataloged by the National Archives.

Months later, after landing at Iwo Jima in February 1945, Mr. Begay and his fellow code talkers were hailed as instrumental in taking the island – and later with helping to win the war. Their code was never broken.��

Mr. Begay returned to America and a high school for Indigenous kids after Japan’s surrender, but it was shut down soon afterward. With unemployment high, he joined the Army. While saluting an instructor during training, he was asked, “Are you looking for Indians?” and ordered to give 10 pushups. “I guess it’s comical. I didn’t get offended. No such thing then.”��

Today, Mr. Begay is living in a house where bad plumbing has damaged the floors and ceiling. “It’s not safe for him,” says Karen Shirley, community coordinator for DNP, which is helping him apply for VA grants to fix up his home, or get Mr. Begay a new one.��

“How can we not support this great warrior who helped save this country, and just get him the housing he needs?” Ms. Tyler says.

While there are roughly 17.5 million veterans in the U.S., only some 9 million are enrolled in the VA health care system, notes Jim Lorraine, president of America’s Warrior Partnership, a veterans service organization that acts as an umbrella group for the DNP and other nonprofits that support Native American vets.��

��

Building relationships “before ... they need it”��

In the Navajo Nation, self-harm is very much looked down upon, but depression due to poverty or post-traumatic stress frequently takes the form of alcoholism and drug use, advocates say.��

“We don’t talk about suicide – it’s taboo. We talk about improving quality of life,” Mr. Lorraine says. “If I have good housing, good employment, connection to spirituality, my quality of life goes up, and the suicide risk goes down.”

To date, the DNP has connected with some 1,228 of the estimated 14,700 veterans living on the Navajo Nation. It has also worked with some 370 partner groups to fund more than 1,100 projects to get veterans assistance with everything from improvements in housing to emergency financial aid.��

The key is “to build a relationship with veterans before they think they need it. We don’t wait for people to come to us,” he adds. “You’ve never helped anyone you didn’t know.”��

Regina Lewis wasn’t looking for help in the years after she served in the U.S. Army as a radio mechanic. She enlisted in large part to prove to her family her ability to stand on her own two feet.��

“My uncle told me, ‘You know, you’re not going to make it – you’re too girlie.’ I wanted to prove him wrong.”

Once she returned to the reservation after completing her service in Germany and Texas, she found that as a female veteran, “We’re not as recognized,’’ she said. “When they honor people, it’s the military men.”

She didn’t feel inclined to join local vets organizations.��

This is a common sentiment among female veterans here in a “male dominated” culture that is also heavily maternal, Ms. Tyler says. When women finish their service, the sense can be, “‘OK, now we have to go home and be the nurturers that we are.’ They don’t try to be seen as veterans,” she adds.

Out of the loop of service culture and often without access to reliable technology, many aren’t aware of the VA services available to them. Part of the challenge is getting the word out.

For Ms. Lewis’ part, even though she finished up her Army duties 30 years ago, she just recently learned she’s eligible for VA care.

“I’m new to the whole system – I didn’t know about these services,” she says. She is now getting coverage for service-incurred hearing loss and soon, she hopes, for help building a water tank on her land.��

It needs to be refilled monthly, but it’s better than hauling water from friends’ places for a bath, as she did this morning, she notes.

Through consistent acts of service, the hope, Mr. Lorraine says, is to help Native American veterans grow in trust that “we have their back – no matter what they face.”