'Grim Sleeper' case raises privacy concerns over use of DNA

Loading...

| Los Angeles

To break the "Grim Sleeper" serial killer case in California, authorities used a controversial new law that allowed them to take DNA from the suspect's family members. The evidence led to the arrest of a man suspected of murdering at least 10 women in Los Angeles over 25 years.

Is it a breakthrough in police science? Or does it have the potential for privacy invasion? Such questions are now being debated by law enforcement officials and legal scholars.

Lonnie David Franklin Jr. was arrested July 7 on multiple murder counts after the state DNA lab uncovered a link between murder scene material and Mr. Franklin’s son, Christopher.

Last year, Christopher was convicted of a felony weapons charge and his DNA was collected and sent to the state DNA data bank. Initial searches to find the “Grim Sleeper” suspect under the new program that same month failed to find a relative in the database. A second search this spring was successful.

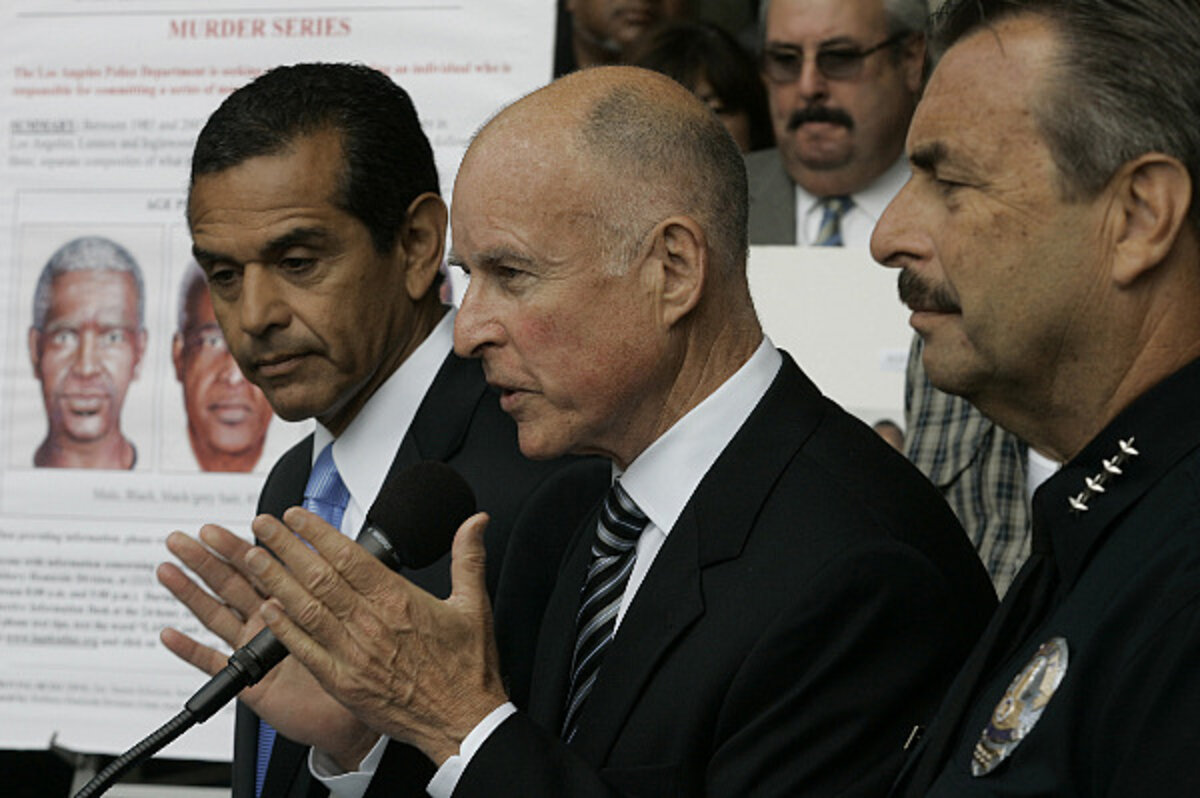

At a press conference Thursday, the mayor, police commission president, Los Angeles County sheriff, victims’ family members, and detectives all lauded the new procedure.

'This will change the face of policing'

“This will change the face of policing in the United States,” said LAPD Chief Charlie Beck, speaking of the new technique. California became the first state to adopt the new search program in 2008, and it has been used only 10 times since its inception.

“The suspect would still be at large except for the familial search program,” said California Attorney General Jerry Brown.

Here’s how the procedure works: Crime scene samples are compared to the DNA of convicted offenders in the state database to see if they match. Forensics experts examine how many of the DNA markers are shared and how rare the markers are.

“Now we’ve proven how important this forensic technology is by tracking down a suspected serial killer who terrorized Los Angeles for more than two decades,” said Attorney General Brown. Still, he acknowledges criticism of the technique based on privacy concerns.

“In the face of a multitude of objections, we’ve crafted a balanced policy to respect the rights of citizens and at the same time deploy the most powerful DNA search technology available,” he said, emphasizing that familial DNA searches are done under rigorous guidelines and that they are only allowed in major, violent crimes when there is a serious risk to public safety.

But law enforcement specialists around the country are wondering about the moral and ethical aspects of this new method of solving crimes.

“This does not violate the US Constitution’s Fourth Amendment protections against unlawful search and seizure,” says Tod Burke, professor of criminal justice at Radford University in Virginia. “But the bigger question is moral and legal: Is this Big Brother? And the answer really is, ‘Yes.’ ”

Professor Burke and others ask how far this kind of investigation will go.

“The government has justified the collection and retention of the DNA in the database on limited and specific grounds, but now they are pushing out into new, possibly unforeseen uses for the DNA,” says Anne Bowen Poulin, a professor at Villanova University School of Law.

“As science progresses, the government may find additional unforeseen uses, some with more negative impact on the source of the DNA,” Professor Poulin says. “Good police work? Most would probably applaud it. Risk to privacy? We probably won’t know until it’s too late.”

The ACLU has weighed in on the “Grim Sleeper” case, named for the many years that passed between the crimes.

“If you are going to use familial DNA testing, this is probably the case for it,” says ACLU staff attorney Peter Bibring. “But it is a mistake to think this should or could be used all the time.”

Serious privacy concerns raised

DNA collection raises serious privacy concerns because it carries so much information about the person’s health and family relationships, Mr. Bibring says. “It’s not just about criminal activity, it’s so much more than that.”

Others note that because this technique is so new, not much regulation exists, and therefore there is likely to be many court challenges.

“Privacy concerns raised by the use of familial DNA to crack the 'Grim Sleeper' murders may create significant problems for the prosecution, should a defense attorney challenge the evidence,” says James Alan Fox, professor of criminology, law, and public policy at Northeastern University in Boston. He calls the arrest in the “Grim Sleeper” case “surprising” and “unusual.”

“Laws permit the collection and storage of DNA data on certain convicted offenders for use in potentially linking future crimes to these same criminals, but not to their blood relatives who happen to have similar genetic profiles,” he says. “This is not so much a concern for the slippery slope of privacy invasion, but a case of legal quicksand.”

Related: