Room for everyone: Tribal college expands its reach

Loading...

| TOHONO O’ODHAM NATION, Ariz.

Deep in the Sonoran Desert, near the Arizona and Mexico border, picnic tables under ramadas at Tohono O’odham Community College sit empty. A new amphitheater for songs, prayers, and ceremonies is silent under a November sun.

But the college, located on the Tohono O’odham Nation, about an hour west of Tucson, has more students than ever – just not on campus.

During the pandemic, the college, founded in 1998 to serve its tribe, moved all its courses online and offered them without charge to any Native student. Enrollment nearly doubled to more than 900 students. Tohono O’odham had the largest increase of any tribal college – 96% in 2020.

Why We Wrote This

Can a tribal college support its own community’s culture while also enrolling students from many other Native American groups? One school in Arizona is committed to trying.

Students liked online courses and free tuition so much that when the college reopened this fall, they didn’t return to campus. And the college grew more diverse. There are now 55 tribal nations represented among students where there used to be eight or nine, says Paul Robertson, president of the college. The increasing diversity is changing the composition of a campus rooted in serving the Tohono O’odham people, prompting concern about the small college’s identity and the best way for it to contribute to Native education.

College deans, faculty, and employees have met together in recent weeks to address what initially Dr. Robertson says was “an existential crisis” that raised the question: “What are we?”

The question echoes throughout Indian Country, as tribal colleges and universities, largely federally funded and founded to serve their specific communities, strive to meet a vast need among Native students for higher education.

The colleges “counter some really negative forces in our culture in terms of giving up your background,” says Jon Reyhner, professor of education at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff and co-author of “American Indian Education: A History.” “Knowing your history breeds resilience.”

The Tohono O’odham Nation founded its college, one of about 35 tribal colleges nationwide, with the aim of preserving the culture and traditions of a people whose ties to the region date back thousands of years. But Dr. Robertson, the college president, says the immense need among all Native students suggests the college has a purpose beyond its tribe. “There’s a lot of students out there,” he says. “I think we’re starting to see that.”

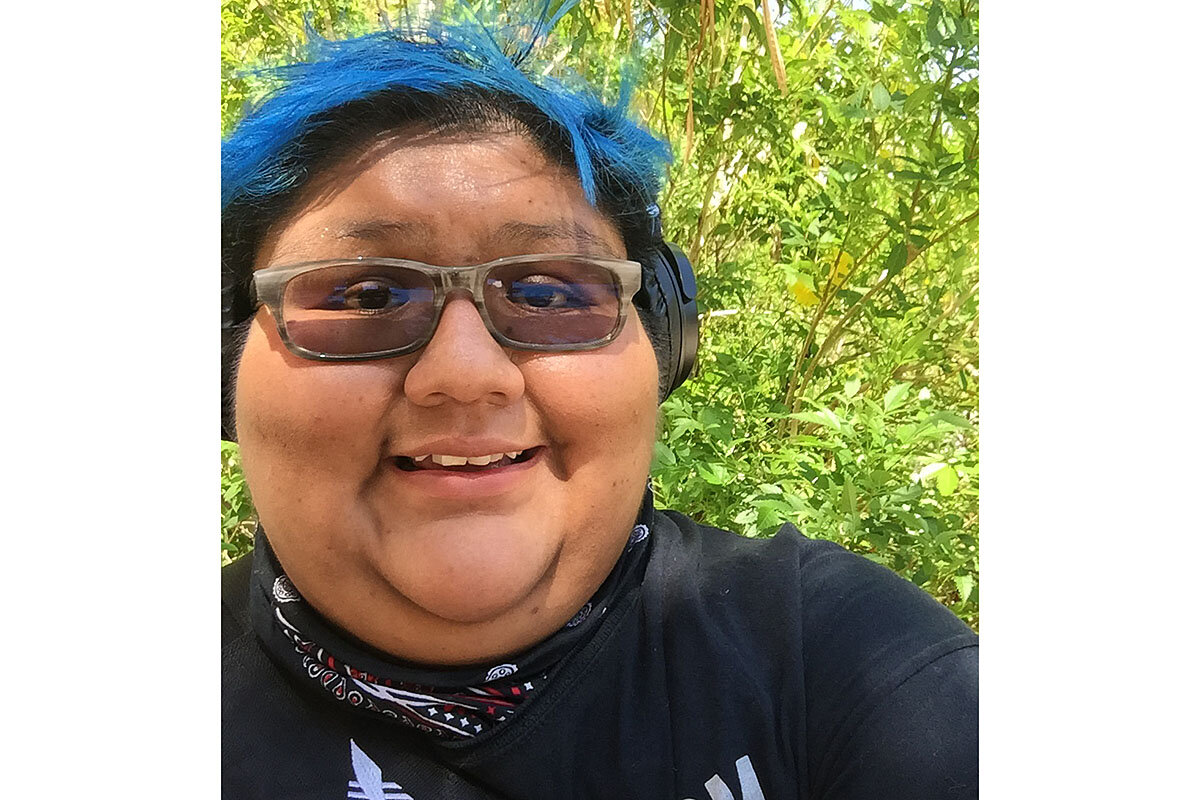

Josie Pete of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah says she likely would not have been able to enroll at Tohono O’odham Community College a year ago without the availability of online classes and free tuition since she was working from her home on the Utah reservation.

“It was something that was convenient,” she says. “I didn’t really have to wonder, ‘How am I going to pay for school? How am I going to pay for books?’”

Ms. Pete wanted to study art and the college sent her supplies, including sketchbooks, pencils, paints, and charcoal. “The school believed in me enough to send me the supplies,” she says. “It was just really special.”

Though she is from another tribe, Ms. Pete says she has enjoyed taking the required Tohono O’odham language and history classes. “I’m actually all for it,” she says. “It’s unique to learn about another culture that is similar to my own.”

When she finishes in about a year, she intends to go to a four-year institution where she also can study online for a bachelor’s degree in art, and eventually become an illustrator.

Feeding a hunger for education

Tohono O’odham Community College has been able to accommodate additional students, like Ms. Pete, through a combination of federal funds and support from the Tohono O’odham Nation, which provides about 42% of the college’s annual budget, according to Dr. Robertson. Federal funding to tribal colleges and universities is only given for Native American students, who make up 95% of students at Tohono O’odham.

The school is a model for what other tribal colleges and universities can achieve through developing a strong online presence, says Carrie Billy, president and CEO of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

“That’s exactly how we want to serve Native people, wherever they are,” Ms. Billy says. “There’s a hunger for culturally grounded education.”

Drawing Native students from all over online can only bolster college attainment among American Indians, says Ofelia Zepeda, chair of Tohono O’odham Community College’s Board of Trustees and Regents’ professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “It’s just great to see because it has been so long in coming.”

American Indian graduation rates have long been a struggle: 15% of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared with 32% of Americans in that age group, according to census figures. In Arizona, home to one of the nation’s largest Indigenous populations, the numbers for both groups lag even more, with 11% of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 25 and older holding a bachelor’s degree or higher compared with 29% of Arizonans in that age group.

Studies have shown that the culturally enriched experience at tribal colleges feeds students’ success. Native language, culture, and history courses about their tribes are key to the curriculum. That’s the point of a tribal college or university – to build and reclaim community. Schools are evaluated based on their tribe-specific relationships. The tribal college movement of the late 1960s and 1970s grew out of the oppression and frustration many American Indian children experienced after decades of forced assimilation to Western customs in boarding schools. Most tribal college graduates stay on or return to their reservation.

The Tohono O’odham Nation, one of the nation’s largest in land area at nearly 3 million acres, has about 34,000 enrolled members, including those who live in Mexico, says Bernard Siquieros, vice chair of the college’s board of trustees.

The tribe founded the college to “provide an opportunity for our young people to have a good starting place in their higher education journey,” Mr. Siquieros says. The teaching of the nation’s language, history, and culture – known as – is a key part of the curriculum. But welcoming students from other tribes helps all Native students and the college, he says.

Still, the college balances that with its original mandate. Some students from other tribes ask about taking a class in their own tribal language, but that’s not what Tohono O’odham Community College is, says Alberta Espinoza, college counselor. Students understand, she says, when she tells them, ‘This is Tohono O’odham Community College,’ and they don’t have to pay any tuition as a Native student, she says.

“The universal Indigenous world view is like, ‘This is a gift,’” Ms. Espinoza says. “You just don’t look a gift horse in the mouth. And so, you be respectful. You take what is given to you and then you move on from there.”

“It felt like a family”

Officials want students back at the physical campus, offering incentives like free meals and gas vouchers. And there are plans for a completed wellness center and a four-year degree in Tohono O’odham studies.

Caralina Antone, now working toward her bachelor’s degree at Arizona State University, credits the college’s supportive atmosphere with helping her get back on the college path.

“They continued to encourage me,” she says. “It felt like a family. … You’re not alone.”

Many Native people, like Ms. Antone, live in urban areas but want to attend tribal colleges, which are often in rural and remote places. Ms. Antone, an orphan raised by her grandmother, wanted to go to Tohono O’odham’s college because that was her grandmother’s tribe. At first, she commuted nearly six hours daily from the Phoenix area to the college and back. “I got up at 3 a.m. to be out the door by 4:30,” she says. “I wanted to honor her and complete school.”

She missed having in-person classes after the pandemic started, but adapted to the online work. She was the college’s student of the year when she graduated in 2020. She hopes to become a social worker and help adolescents.

“You need to finish what you start,” she says. “I’m glad I got through it.”

Tohono O’odham Community College officials met last week and are “united” that the college’s “mission will continue to be the same” as the college faces a future rooted in serving students from many more tribes, Dr. Robertson explains in an email.

“Through much discussion we have reached a consensus that we can accommodate the changes,” he notes, “and still maintain our identity.”