On California ballot: Housing’s role in addressing mental illness

Loading...

| Los Angeles

A soft knock on her office door interrupts Olga Recendez, the administrator of a group home for adults with severe mental illness. She rises from her desk and opens the door to find a resident holding artwork: It’s an outline of a cat, loosely colored in with hot-pink marker and dotted with hand-drawn flowers.

Ms. Recendez praises the artist and clips the piece to a collection of similar treasures on a whiteboard. The resident, a willowy woman diagnosed with schizophrenia, also has a question. Will they do something special for her birthday? ‚ÄúYes,‚Äù Ms. Recendez reassures the woman, not named for privacy reasons. ‚ÄúYou are special.‚Äù The resident seems pleased, and the administrator gently closes the door.¬Ý

“These are the few things that make a difference,” says Ms. Recendez, who works here at the ASC Treatment Group, a privately owned facility for 37 adults in a Los Angeles residential neighborhood. “You just need that one-on-one.” It’s one of the reasons the client has succeeded in living here for more than a year – remarkable, given her history of psychiatric hospitals, failed community placements, and urge to run away. Absent this supportive environment, she could “very, very easily” become homeless, says Ms. Recendez.

Why We Wrote This

As states face rising homelessness and mental illness, Californians are seeking solutions. They will soon vote on Proposition 1, which would help people get off the streets and into homes and places for treatment.

As states across America grapple with the twin challenges of rising homelessness and mental illness, California’s counties are clamoring for more places like ASC. But there aren’t enough of them. Neither is there enough affordable housing in this expensive state. Despite billions spent in recent years, homelessness has increased, and many unhoused people struggle with mental illness and addiction. All of this has rolled into a perfect storm impacting public health and safety, businesses, and quality of life – making homelessness a top concern for California voters.

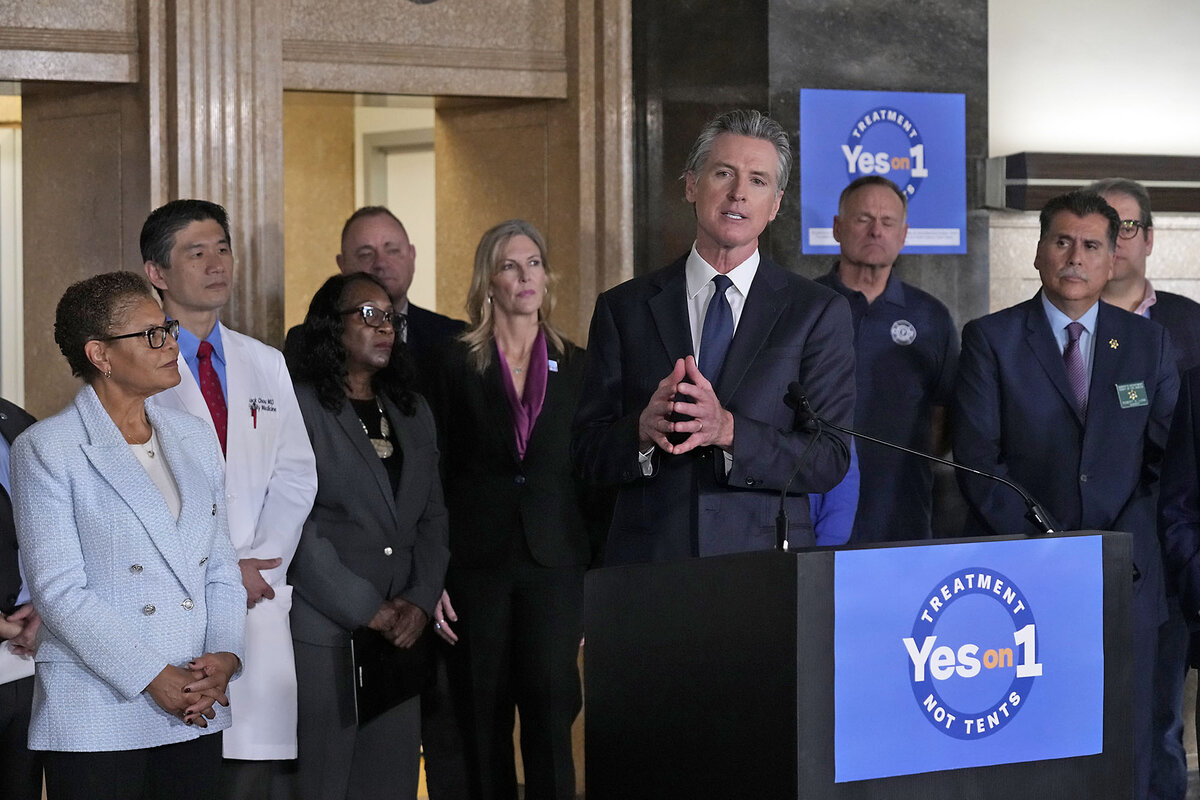

Politicians, not surprisingly, are under tremendous pressure to do something. Their latest effort, , which will be on the March 5 ballot, would overhaul the state’s mental health system to firmly link it to housing. For the first time, counties would be required to spend behavioral health dollars on housing for homeless people with mental illness and addictions. Proposition 1 also includes a $6.4 billion state bond to secure supportive housing and treatment places for homeless people, with $1 billion for veterans. Gov. Gavin Newsom dubs it “treatment, not tents.”

The measure has its critics. One main objection is that more county behavioral health dollars for housing means fewer for mental health services. While the ballot measure promises more than 11,000 places for treatment and living, the independent state legislative analyst says the new measure would reduce statewide homelessness ‚Äúby only a small amount.‚Äù Yet the legislation behind the measure passed with near unanimity in Sacramento last year.¬Ý shows nearly two-thirds of likely voters support it.

‚ÄúIn a perfect world, you wouldn‚Äôt be robbing Peter to pay Paul,‚Äù says Dr. Margot Kushel, director of the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at the University of California, San Francisco. But given funding constraints, ‚Äúwe really don‚Äôt live in a perfect world.‚Äù¬Ý¬Ý

This is not a new problem for California. Homelessness in the Golden State is by far the highest in the nation, in 2022. That’s a third of the total national count and far outpaces second-place New York. Last year, the Benioff initiative conducted the study of homelessness ever undertaken in California. Two-thirds of participants reported symptoms of current mental health challenges. Only 18% had recently received nonemergency mental health treatment. One in 5 who used drugs or alcohol said they wanted treatment – but couldn’t get it.

Even if the ballot measure won’t reach as many people as need help, Dr. Kushel says its significance lies in the marrying of mental health with housing. “There is no medication as powerful as housing,” she says. “There is no amount of fancy health care that I can provide for someone that can really do much if they are still homeless.”

Consequences of closing state hospitals

The nation, including California, is still grappling with the seismic mental health shift of the 1960s – the closing of America’s ill-famed state psychiatric hospitals. No one wants to go back to the asylums that warehoused patients in locked wards, often for decades. The 1975 film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” dramatized this hidden world, ending with the main character’s tragic lobotomy. The film swept the Oscars.

President John F. Kennedy tried to create a landing place for the newly discharged patients by setting up community mental health centers in the early 1960s. By 1977, nearly 400,000 state hospital beds had disappeared. But only 5% of those discharged patients were reappearing in the new local mental health centers, which mostly handled less acute cases, according to ‚ÄúHealing: Our Path From Mental Illness to Mental Health,‚Äù a book by Dr. Thomas Insel, former director of the National Institute of Mental Health.¬Ý

At the same time, the Vietnam War sent home veterans who were struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder and addictions, left to fend for themselves. ‚ÄúA whole range of things came together, and that really was the beginning of the homelessness epidemic,‚Äù says Dr. Insel in an interview.¬Ý

Compounding this, in 1982 President Ronald Reagan sent federal funding for mental health community centers back to the states as block grants. Many states had other priorities and pressures. They focused instead on building prisons and jails, which have become de facto mental health institutions.

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs an absolute disaster for people with these illnesses,‚Äù says Dr. Insel about those who end up in jail. Proposition 1, he says, tries to undo some of this history and help ‚Äúthis very neglected part of the population who has always had a very treatable illness.‚Äù¬Ý

Housing and care together

Stephanie Klasky-Gamer is giving a tour of The Fiesta, an apartment building in North Hollywood designed for those who are chronically homeless with severe and persistent mental illness.

It’s run by her nonprofit, , and is the type of housing that could be covered by Proposition 1, if it passes. Known as permanent supportive housing, it’s independent living, with supportive services for those who want them.

Stepping out of the elevator, Ms. Klasky-Gamer greets a resident, Joseph. Seven years ago, he was living under a freeway overpass. This afternoon, he’s carrying two new king-size pillows up to the studio apartment that he has called home since The Fiesta opened in January 2017.

This is how you measure success, says Ms. Klasky-Gamer, president and CEO of LA Family Housing: ‚ÄúThat he is stable. That he is able to go out and buy two new pillows for his bed, because literally he came in with nothing.‚Äù¬Ý

She remembers the initial move-in day for residents. “It was pouring out,” she recalls, “and people came in with trash bags, dragging their belongings. That he’s here seven years later, looking healthy, able to use his fixed income to take care of himself – that’s pretty good.”

What‚Äôs made the difference, she explains, is having housing and services in the same place. The nonprofit owns and operates more than 30 properties across the county ‚Äì from converted hotels to new buildings. That integration model is showcased here at its headquarters, a contemporary campus designed by Ms. Klasky-Gamer, alongside an architect.¬Ý

Tall glass windows let in shafts of natural light. Courtyards and planters invite socializing – or relaxing. The campus features a health center, dental clinic, on-site case management, and spaces where visiting professionals can offer services like legal advice and employment help.

Families and adults transitioning from homelessness live in interim residences on one end of the campus. The Fiesta, with its 49 studio units, is on the other end. Each apartment floor has its own case manager, located across from elevators and near mailboxes so that counselor-resident interaction is a daily routine. That’s important because accessing services is voluntary.

Ms. Klasky-Gamer backs Proposition 1 because of the need for capital investment in housing after decades of slow-growth policy in Los Angeles. In 2022, homelessness in Los Angeles County reached , up 9% from the year before.

“Without the housing itself, we will make no dent in ending homelessness,” she says.

Moneys from Proposition 1 can’t come soon enough for LA Family Housing. Her organization has 750 permanent supportive housing units in the pipeline. Without those, she says, people moving up from interim housing have nowhere to go.

Proposition 1 side effects

Proposition 1 takes up 68 pages in the voter guide. Not exactly an easy read. It would overhaul a law that voters passed two decades ago when they approved a ‚Äúmillionaires tax‚Äù for mental health services. It was considered revolutionary at the time and raises $2 billion to $3.5 billion each year.¬Ý

Proposition 1 would change that setup in key ways. It adds substance abuse to the ills covered by the tax. It directs a small slice of the tax to training mental health workers, of whom there is a huge shortage. And it requires county mental health departments, which get most of the tax revenue, to divert 30% of those funds to housing that runs the gamut, from group homes, to motel conversions, to secure facilities.

But there is pushback. A group called argues that diverting a third of the tax dollars to housing would hinder current, effective mental health services – like early prevention, outpatient treatment, and crisis intervention.

In San Diego County, for instance, the millionaires tax supports a network of crisis stabilization units – alternatives to emergency departments. Staffed with mental health professionals and peer supporters, they help people access care closer to families and support services, explains Luke Bergmann, director of the county’s Behavioral Health Services.

The stabilization units “have had some pretty dramatic impacts on access to care,” says Dr. Bergmann. If he loses those funds, he asks, “where will I find money for this core behavioral health care service?”

While he welcomes Proposition 1’s emphasis on infrastructure, he says it’s asking counties to do more with less. A silver lining, he hopes, would be if this forces a discussion about how to fully integrate behavioral health care with general health care, instead of having it siloed off with special funds and programs as in Proposition 1.

Supporters acknowledge the funding trade-off, but they say the focus must shift to housing. “The nature of our mental health crisis and homelessness have changed a lot over the last two decades,” says Anthony York, a spokesperson for the . “We have to be able to prioritize.”

Critics target another issue: locked facilities and forced care. California now has only one-sixth of the psychiatric hospital beds it had in the 1950s, which is not enough for some mental health advocates. But others oppose Proposition 1‚Äôs provision for more locked settings.¬Ý

“It’s really hiding the problem, not solving the problem,” says Paul Simmons, one opposition campaign leader.

In recent years, the state has also broadened the legal framework for conservatorship, which allows a judge to appoint a decision-maker for those who can’t manage alone. Civil rights advocates and others have fought this trend, arguing that forced treatment violates a person’s liberties and can make conditions worse.

Alex Barnard, author of the book ‚ÄúConservatorship:¬ÝInside California‚Äôs System of Coercion and Care for Mental Illness,‚Äù sees Proposition 1 as a harbinger of a nationwide shift toward more restrictive, high-level mental health settings. He notes New York‚Äôs nearly $1 million fine¬Ý last year for failing to bring dozens of psychiatric beds back online after the pandemic.

“You’ll hear inflated or exaggerated claims that we’re going back to the mass institutionalization of the 1950s,” says Mr. Barnard, an assistant professor of sociology at New York University. “But I don’t think that’s happening.”

The Proposition 1 campaign says the emphasis on locked facilities is misplaced and expects that much of the new housing will be¬Ýbuilt for higher-functioning people.¬Ý

An investment that paid off

Back at the residential facility in East Los Angeles, ASC executive director Michael Rosberg questions how wisely those Proposition 1 dollars would be spent. Too often, he says, housing is built to work for staff, not those they serve. Like Ms. Klasky-Gamer, he’s a believer in human-centered design as a way to improve mental health outcomes. He’s applying those concepts in a completely different setting that could also be covered by Proposition 1.

ASC runs two treatment residences, as well as an outpatient clinic. But unlike The Fiesta, these are communal living, two-to-a-room, with 24-hour board and care in what‚Äôs called adult residential facilities. ASC‚Äôs clients typically come from acute and locked settings. Most are indigent, on disability. They stay for about 16 months to stabilize and then move to more independent arrangements with wraparound services ‚Äì places like The Fiesta. Sometimes they return to family.¬Ý

On a bright winter day in January, Dr. Rosberg is at the ASC site in Los Angeles, mingling with a few residents on recently landscaped grounds. The peaceful setting, with snowcapped mountains as backdrop, is an investment that has paid off in dramatically improved client behavior.

With a government grant that helped replace turf with drought-resistant landscaping, ASC has transformed its 2-acre site from a patchy, grassy area that people didn’t use to one of healthy ground cover and intersecting gravel paths that lead to social spaces. Benches, a pergola, and a vegetable garden allow for togetherness, while a big tree at the property’s edge provides a private haven where one client rests. It’s his favorite spot.

“We wanted it to be wonderful for the people who live here,” says Dr. Rosberg, a licensed psychologist. “What we didn’t expect was that our clients improved dramatically.”

He ticks off the results: a 70% reduction in substance abuse¬Ý(even though residents are free to go into the community, where drugs and alcohol are¬Ýeasily available); a 34% drop in use of emergency medicines for psychiatric crises; a 70% decrease in the number of people who have run away; a 54% reduction in crisis-driven, staff interventions.¬Ý

An added benefit is that families of the residents want to visit them on campus. They bring lunch and hang out, instead of whisking their relative away to a noisy restaurant.

ASC changed nothing else ‚Äì not the staffing, not the daily meal and snack routine, not the morning meds and therapy, not the activities and small jobs. And¬Ýnot the kindness and acceptance.¬Ý

‚ÄúThe implications for environmental therapy as a component of¬Ýservice are very significant,‚Äù says Dr. Rosberg. Especially for clients who¬Ýare treatment-resistant, as is the case at the ASC facility, ‚Äúit could have a¬Ýprofound effect on the use of resources.‚Äù