Now playing: Hollywood’s dystopian view of Silicon Valley

Loading...

The techno-exuberance on full display in “The Circle,” the movie adaptation of Dave Eggers’s 2013 book, is all too familiar for anyone who’s listened to Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk lately.

The founder of Facebook is on a mission to connect the entire planet “to amplify the good effects and mitigate the bad.” And the Tesla chief executive wants to colonize Mars.

It’s heady stuff. And it’s that kind of wide-eyed, shoot-for-the-stars (literally), disrupt everything, innovate-first-and-ask-questions-later attitude that “The Circle,” along with a growing body of films and TV shows, are questioning. Just how much power should the likes of Mr. Zuckerberg, Mr. Musk, and the other tech industry visionaries have over our daily lives? Where are they taking society? And do we want to go along for the ride?

“The Circle,” named for a fictional social media company that resembles a mash up of Apple, Facebook, and Google, is just Hollywood’s latest critique of a software-driven society. Remember the 1983 film “WarGames” and the computer that nearly destroyed civilization? And sci-fi films have long forecast dystopian futures in which computers threaten human survival – from HAL 9000 in "2001: A Space Odyssey" to Skynet in "The Terminator."

But now writers and directors are increasingly turning their attention to how technology affects more intimate and personal interactions: How we communicate, how we show affection, how we reveal our deepest thoughts and feelings, and whether personal privacy is a memento of the analog age.

In many ways, the growing body of work – in books, films, and television – critiquing Silicon Valley is about “the amount of power these companies have,” says Noam Cohen, a tech writer and author of the forthcoming book “The Know-It-Alls: The Rise of Silicon Valley as a Political Powerhouse and Social Wrecking Ball.” It’s a cultural response to their influence, he says.

Often the problem with how Silicon Valley views the world, he says, is that “everything is an engineering problem.” Developers may perfect a frictionless, real-time video platform or build a smarter robot he says, but that doesn’t mean society has to accept those machines, Mr. Cohen says. “Do we have to go there even if it’s not the best for all of us?”

Critique of technology, and its purveyors

For instance, the most recent season of Netflix’s “Black Mirror” offered a dark and unsettling critique of technology, beginning its third season last fall by portraying a life in which everyone is instantly judged by a social media score sheet. HBO’s “Westworld” imagines a future in which robots appear so human that real humans can’t differentiate between people and machines. And the most recent season of “Homeland,” the Showtime spy drama, included a subplot about an online fake news operation that was eerily similar to the Russian propaganda campaign ahead of the most recent presidential election.

One of the most stinging critiques of Silicon Valley comes from “Silicon Valley,” the HBO comedy from writer and director Mike Judge (who directed the films “Office Space” and “Idiocracy”). Last year, Andrew Marantz of The New Yorker called it the “first ambitious satire of any form to shed much light on the current socio-cultural moment in Northern California.”

“Silicon Valley” not only demystifies tech culture in ways that make it seem downright drab and often depicts the Northern California tech bubble in dark terms (making poignant statements about how tech companies and venture capital firms treat female engineers and immigrants).

The series is at its best when it's lampooning startup culture. Doree Shafrir's new novel "Startup" also takes jabs at the pretentiousness that's all too common among the young and brash tech workforce. She opens the books by describing a social media company's early morning dance party for its employees. "They posted this moment on Snapchat and Instagram, on Twitter and Facebook, anywhere that their message – I was here – could be loudly, clearly received."

Luddite's version of social media?

Neither the TV show nor the book paints nearly as a dark portrait about the overall internet economy as “The Circle,” directed by James Ponsoldt, who cowrote the movie with Eggers.

When Eggers’s book came out, it was panned by tech journalists as a luddite’s version of social media gone awry. In both book and movie, the social media company The Circle hatches an idea to spread tiny cameras around the world that can broadcast anything – at any time – via the web, a system that takes radical transparency (or radical surveillance) to an entirely new scale. And, in true Silicon Valley fashion, it launches the product, turns on the cameras, and waits to see what happens in the real world. Disruption in real time.

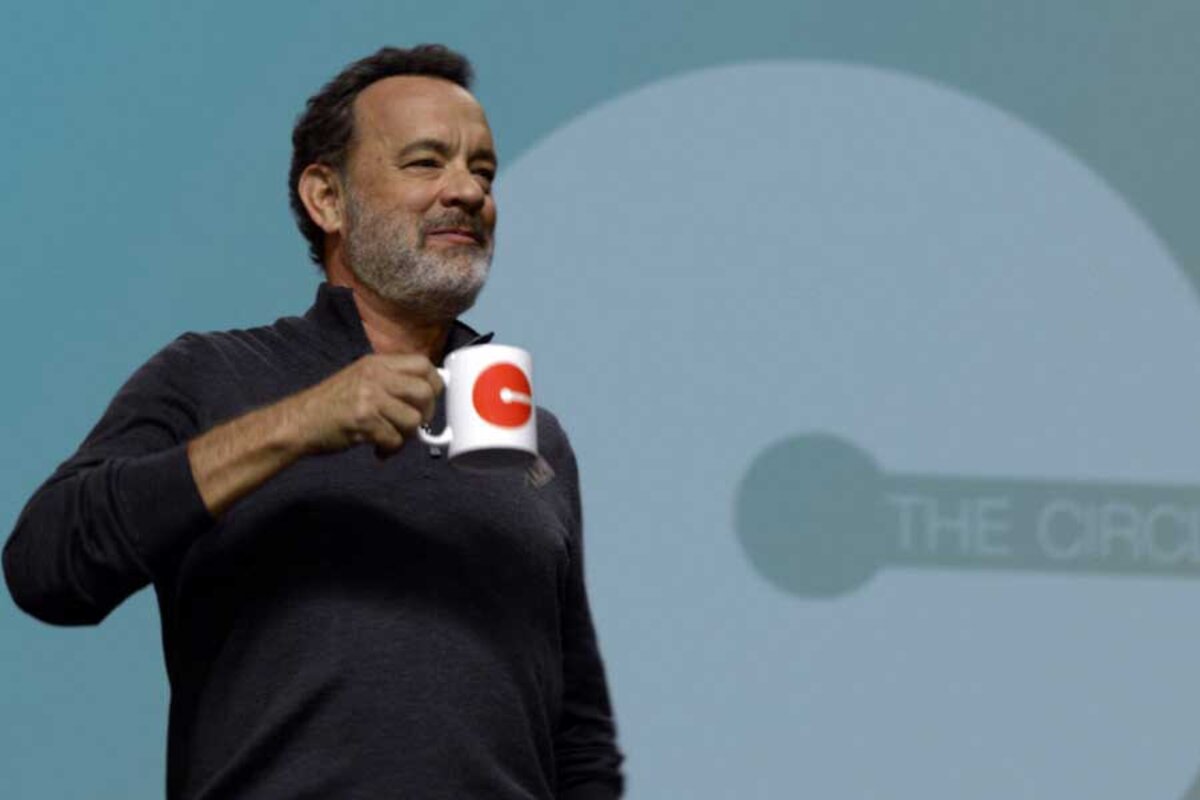

When The Circle’s leader Eamon Bailey (played by Tom Hanks) introduces the SeeChange camera system, he hails it as a mechanism for keeping tyrants and wrongdoers in check. “We will see it all; if it happens, we’ll know,” he says. “Imagine the human rights implications. The need to be accountable. So many of our lies that get us in trouble, the things we hide. We care about everybody you care about, because knowing is good. But knowing everything is better.”

That sort of wide-eyed optimism about technology without regard for any downsides (in this case, the complete end of privacy) isn't that dissimilar to the enthusiasm Zuckerberg showed for Facebook Live, the company's real-time video streaming platform. When it launched last year, he said it would offer users the “the most personal and emotional and raw and visceral ways ... to communicate.” But since then, amid the and , Facebook users have broadcast rapes, abuse, and even murders via Facebook Live. Facebook announced this week it was hiring 3,000 people to review posts and videos that might contain crimes or suicides.

To be sure, “The Circle,” which was widely panned, shows a one-dimensional view of Silicon Valley. It makes its point about privacy in blunt, Orwellian terms (the characters say things like “secrets are lies” and have a rather different take on the Care Bears slogan “sharing is caring”). However, critics say it fails to capture the full scope of how tech intermingles with society and how privacy (in some cases) can accompany a more interconnected world.

A Facebook employee who saw the film told The Guardian newspaper that the company’s employees are hardly “some homogeneous, dumbed-down, clap-for-everything crowd that’s like, ‘Yay! We hate privacy!’”