The future of tech in just one word: plastics

Loading...

In the 2002 movie “Minority Report,” director Steven Spielberg painted the future as a place where no surface was still. Newspapers updated in readers’ hands and advertisements talked to passersby. Even cereal boxes were animated.

Now, these technologies are finally arriving, albeit in a piecemeal fashion. One of the driving forces: breakthroughs in plastics-based electronics.

Such gadgets and displays offer several potential advantages over silicon-based electronics – chief among them, they can be manufactured by a cheaper and less energy-intensive process, they’re potentially more energy efficient, and they can bend.

The plastic electronics industry will be valued at $30 billion by 2015, and $250 billion by 2025, predicts IDTechEx, an electronics consulting company.

“Expect a whole host of innovative new applications to start appearing as plastic electronics comes of age,” proclaims an article in the July issue of Physics World.

Bright start in ‘organic’ TVs

So-called organic light-emitting diodes (OLED) – “organic” because, like all known life, they’re carbon-based – are poised to change everything from visual displays to ambient lighting.

Unlike liquid crystal displays (LCDs), OLED displays have no backlight. Each OLED pixel emits its own glow. This saves materials, energy, and space, allowing for ever thinner electronics. It also permits flexibility, viewing at obtuse angles, and, in some cases, visibility from both sides.

For years, however, OLED hopefuls have struggled with problems of durability and uneven wear. Pixels of different colors tended to wear out at different rates, leaving gaps in prototype screens. Researchers are overcoming these problems, say experts, but now the principal hurdle to a mass OLED display roll-out is the price.

In January, Sony introduced the first OLED TV in the United States. It’s 11 inches wide and only 3 millimeters thick. But this tiny TV – puny even compared to old tube TVs – retails for $2,500 and lasts more than 30,000 hours – half as long as current LCDs.

Right now, Sony views the TV as a statement – “a technology piece,” says Greg Belloni, a company spokesman in San Diego, Calif. “We have shown what we can do with this technology.”

Price aside, the superior OLED display quality has many singing its praises.

“OLEDs have profoundly beautiful color,” says Lawrence Gasman, principle analyst at NanoMarkets, LC, in Glen Allen, Va. “It is very, very impressive.”

Samsung has larger OLED TV prototypes, as do several other companies, but they’ve been slow to hit the mass market.

As the technology catches on over the next several years and prices begin to fall, Mr. Gasman and others imagine a generation of huge ultra high-definition televisions that roll up after use. Thin plastic sheets on office walls may do double duty as monitors. OLED wallpaper could light a room.

The OLED display and lighting market could be worth $10.9 billion by 2012, and $15.5 billion by 2014, according to a NanoMarkets report.

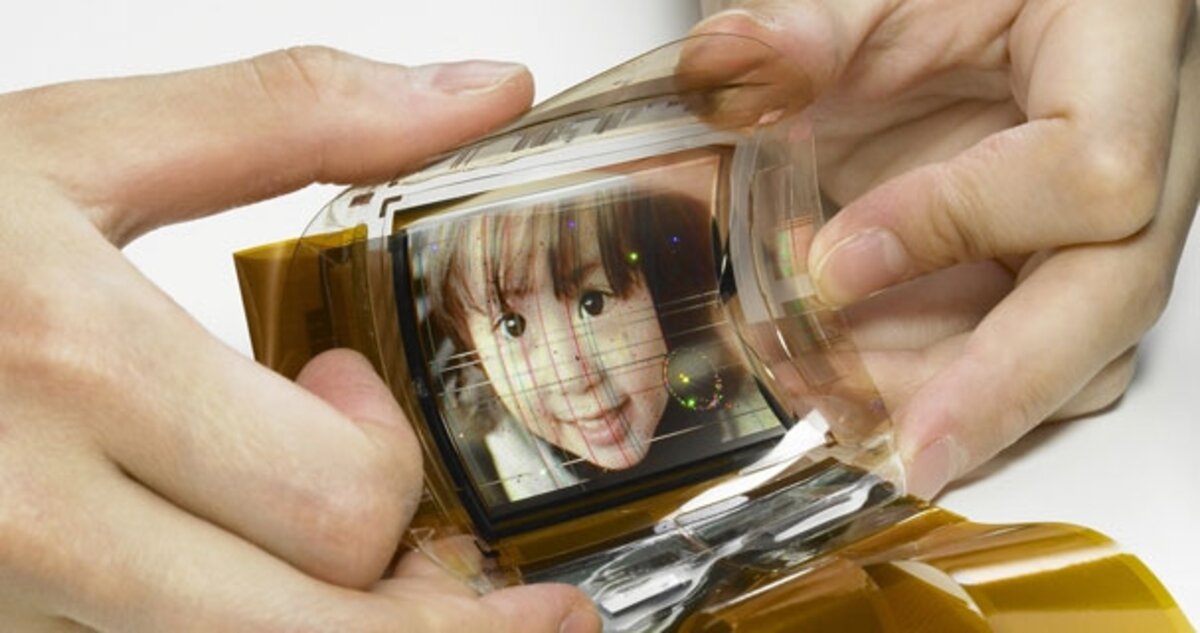

An OLED’s ability to go on a flexible surface – plastic or metal foil, for example – is a major selling point for those seeking improved portability. (OLEDs are already common on cellphones and PDAs throughout Asia.)

Universal Display Corp. in Ewing, N.J., is working with the US Department of Defense on what it calls the “Universal Communication Device.”

Janice Mahon, the company’s vice president of technology commercialization, describes it as an iPhone with a roll-out screen. Rather than lugging numerous maps around, soldiers could one day strap a lightweight, rugged display device to their thigh. The idea: Keep miniaturizing the electronics while maximizing the display.

Flexible displays – LG Display and Sony have prototypes – will likely be on store shelves in the next five years, although they probably won’t be widely affordable for a few more years after that, says Ms. Mahon.

But, she says, “it used to be a matter of if; now it’s a matter of when.”

Thin screens, wide market

The “cool” factor aside, an often overlooked advantage of plastics-based electronics is the potential ease of fabrication, says Gasman.

Making plastic displays doesn’t require parts so much as base materials. So, the electronics can be “printed” roll-to-roll like a newspaper, rather than assembled piece-by-piece like the much more energy intensive process that’s used for LCD displays. This feature will likely reduce OLED manufacturing costs considerably in the future, he says.

DuPont, for example, has spent years perfecting a “nozzle” printer that could cheaply and efficiently deposit the materials on a variety of surfaces, says William Feehery, global business director of DuPont OLEDs in Santa Monica, Calif.

“We are currently making plans to commercialize,” he says. “Our aim is to make it really widespread.”

And then there’s light. In the US, lighting accounts for 8 percent of the nation’s total energy consumption and 22 percent of the electricity used.

The US Department of Energy recently entered a nearly $2 million, two-year contract with Universal Display to develop OLED lighting panels.

They’ll be thin, eventually more efficient than even compact fluorescents (without the mercury, too), and can either be mounted or printed onto many surfaces, says Mahon. One day soon, windows that are transparent by day may emit light by night.

Books that resemble TVs

E-paper is also gradually moving civilization toward a reality of animated surfaces. Amazon’s Kindle, an electronic book reader, is perhaps the best-known example of this technology. The key advance: It only takes energy to “turn the page” – once the text is set, it stops consuming power. There are about 10 other

e-readers on the market, and two or three more about to be released, says Sriram Peruvemba, vice president of marketing for E-Ink in Cambridge, Mass., an electronic paper display company.

Although most current e-readers are rigid devices, they’re moving to flexible surfaces, says Mr. Peruvemba.

Last May, Polymer Vision released the Readius, “the first pocket eReader,” which has a foldable screen and the ability to check e-mail. Both Epson and LG Display have large page-size e-paper prototypes with color. (Black and white is the current standard.)

The goal, says Peruvemba, is to put e-ink on every “smart surface” and get away from the constraints of “dead paper.” One day, subscribers will have one device that updates daily with the most recent edition of their chosen news outlets, Peruvemba imagines.

In that vein, Esquire’s October issue will have an e-paper cover that blinks to commemorate its 75th anniversary.

“I’ve been looking for ways to more fully use the potential of the print medium,” says David Granger, Esquire’s editor-in-chief, in an e-mail message. “The print medium is so compelling that I and we should all be able to do more with it.”

The technology may also lead to a more tree-friendly world. By Peruvemba’s estimate, 95 million trees are cut yearly for books. In the US, 12 billion magazines are printed yearly – and 70 percent of newsstand copies are never sold. Delivering magazines electronically could save the 35 million trees that go into magazines yearly, according to Co-op America, an environmentally minded non-profit. E-paper can offer forests a reprieve.

Solar panels in clothing?

But one of plastic electronics’ truly revolutionary aspects may be somewhat less sexy: to hasten the advent of affordable solar panels. Right now, it takes perhaps 10 years to make back in savings what silicon-based solar panels cost to install, says Alan Heeger, professor of physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and a 2000 Nobel Laureate in chemistry.

“The capital cost of putting in silicon solar cells is just too high,” says Dr. Heeger, who helped start Konarka, a company developing organic solar panels. “We need a technology that will bring that cost down.”

Besides being potentially much cheaper to make, plastic panels can bend, allowing them to be embedded in roof tiles and sewn into bags or clothing. One day you may recharge your cellphone from your handbag’s built-in, plastic solar panel, he says.