Nature-inspired robots swim, crawl, and scuttle like animals

Loading...

| Cambridge, Mass.

When it comes to designing a new robot, some scientists are finding a visit to the zoo more helpful than hours spent at the drawing board. Rather than invent new ways for a robot to navigate a forest or crowded city street, they are copying how animals already do it.

If the goal is to make robots capable of surviving any environment, then nature almost always provides a template, says Joseph Ayers, a professor of biology at Northeastern University in Boston. “Animals have evolved to operate in every environment,” he says.

The movement is part of an emerging field known as biomimetics, which takes designs from the natural world and applies them to everything from architecture to textiles.

In robotics, engineer-biologist teams are finding that automatons based on the same design principles as a lobster or a gecko can overcome many of the challenges that have kept robots from entering the real world. This new school of thought is changing many assumptions about how robots operate, by emphasizing simple mechanics that can replace complex software and sensors.

“We’re in the age that robots are moving out of the factory, out of rather structured environments, into a wider range of applications where the environment is less predictable, and there’s a higher premium on being both physically and operationally robust,” says Mark Cutkosky, professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. He has invented cockroach- and gecko-inspired robots, among others. “One of the things that natural organisms do wonderfully well is cope with unexpected variations in the environment.”

While engineers have incorporated some natural design techniques over the centuries – thorn bushes, for example, are believed to have inspired barbed wire – humans have mostly overlooked natural solutions.

After thousands of years of human innovation, “there’s only a 12 percent overlap between the way humans have solved problems and the way the rest of the natural world has solved problems,” says Janine Benyus, cofounder of the Biomimicry Guild, a consulting firm in Helena, Mont. “[That] means that almost 90 percent of the time when you’re looking to the natural world for a solution, it’s going to be novel.”

Most of today’s robots work like machines, not animals. While advantageous in some respects, it’s an immense constraint in others.

“If you’re controlling a robot with a computer program, unless you’ve anticipated every possible situation it’s going to get into, it will eventually get into a situation where it has no escape strategy and it will be stuck. Animals never get stuck,” says Dr. Ayers. “What animals do is they wiggle and squirm [until they escape].”

Many autonomous robots use complex sensing networks to interact with their environment. They must sense everything that’s around them before making any movement, a serious computational task that animals do instinctively. Biomimetics, however, is beginning to provide robots with the ability to move without carefully plotting every step.

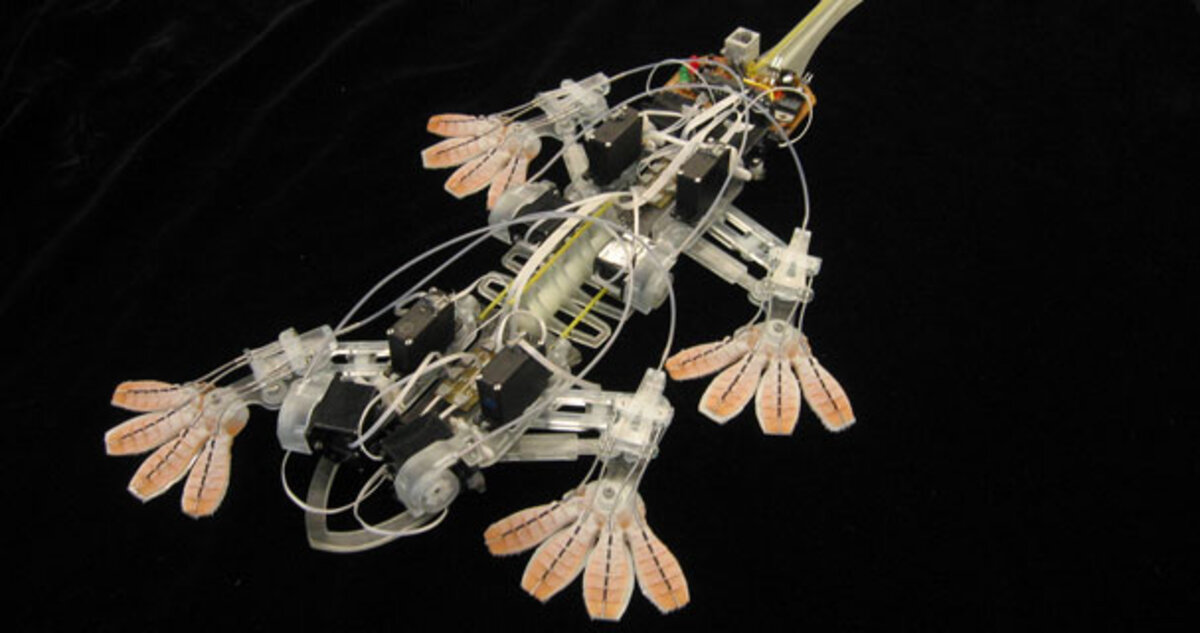

Instead of using complex, expensive sensor networks, Ayers copied the basic physics of how a lobster moves to create a robo-lobster. It reacts with the surrounding environment on something of an intuitive level, he says, not stopping to process what it’s doing or exactly what lays ahead. As a result, the robo-lobster never responds to an obstruction in the same manner. If it gets trapped, it keeps moving until it breaks free.

Dr. Cutkosky’s gecko-inspired robot, Stickybot, also relies on simple mechanics to get around. He and his research team copied the tiny hairs on a gecko’s feet that allow it to seamlessly scale just about any surface. Now his robot can do the same.

“What we’ve been able to learn with the newer bio-inspired approaches to locomotion is that it doesn’t have to be that hard.… They don’t have to be terribly expensive, and they don’t have to have terribly powerful computers and expensive sensors everywhere just to make them run,” says Cutkosky. “Insects don’t have terribly powerful brains and yet they cope pretty well.”

For decades, scientists have tried to re-create the human hand for robots, seeing it as the ultimate manipulator. But the vast majority of robots are still unable to pick up even a cup of coffee, says Harvard University engineering professor Robert Howe. He describes these efforts as an “unmitigated disaster.”

Taking a philosophy that he describes as directly inspired by biomimetics, Howe and graduate student Aaron Dollar, built a hand in 2006 that looks nothing like anything in the animal kingdom, but is capable of picking up anything a human can. Unlike a human hand, which requires 34 muscles to move the fingers and thumb, their robotic hand has only one motor. It relies on springy plastic fingers to naturally grasp an object with the appropriate force. And yes, it can pick up a cup of coffee.

“The idea there is that you put the smarts into the mechanics,” says Howe, describing one of the central concepts for biomimetic robots. “Instead of using sensing and control and computers, you try to build the mechanism so it does the right thing without any of that higher-level supervision.”

Most proponents of biomimetics agree that it’s less about creating carbon copies of nature and more about using it as a starting point.

“Evolution works on the just-good-enough principle, not on the perfecting principle,” says Robert Full, a professor of integrated biology at the University of California at Berkeley.

“So you need biologists who understand not just how organisms work, but how they came to be. Otherwise, you’re going to be getting advice that may be ineffective, that may be not as good as you just doing it with your own engineering solution,” he says.

When Dr. Full was building an underwater robot based on a crab, he initially suggested that each leg have 18 motors because a crab uses the same number of muscles to control each limb. After some consideration though, he realized that those 18 motors could be replaced by two and it would still move like a crab.

“You might say, ‘Why does the crab have all those other joints? What is it doing?’ The crab also fights with other crabs, it mates with other crabs,” says Full, “Robots don’t do that yet, and maybe we don’t want them to do that.”