Who owns the moon? Competition heats up for Google's Lunar X Prize.

Loading...

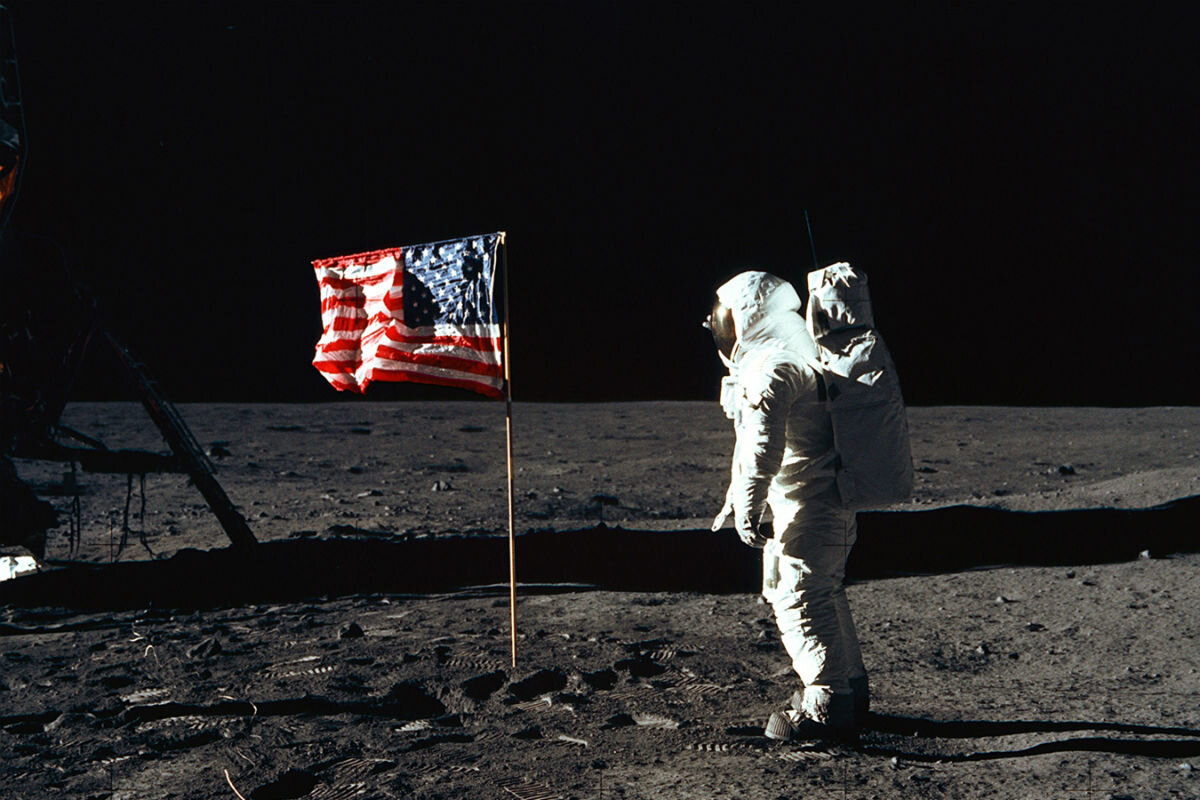

A small step for a private company might turn out to be a giant leap in the new commercial space race to the moon.

The US-based Moon Express announced on Friday that it has all the funding it needs to land its first rover on the moon. It joins a handful of other teams competing for Google’s Lunar X Prize, which aims to open up private pathways to Earth’s only satellite. As commercial exploitation of the moon and other celestial objects becomes more realistic, international discussion of the legal ramifications is heating up.

Google is offering a $20 million dollar payday to the first team to complete three tasks: land a spacecraft on the moon, drive 500 meters, and transmit high-definition footage back to Earth. A runner-up will receive $5 million. The catch? The winning team must carry out their mission , using almost exclusively private funding.

One of the five hopefuls is Moon Express, who made history in August when it became the first company to receive permission to engage in commercial activity beyond Earth orbit from the US government. Now, having raised a reported $20 million in "Series B" funding, they have in place to shoot for the moon, said chief executive and co-founder Bob Richards in a statement.

With the legal and financial hurdles out of the way, “[n]ow it’s ,” Mr. Richards said. And that rocket science stuff is far from guaranteed. The company has secured a contract with US Aerospace corporation Rocket Lab, which plans to early this year.

But Moon Express’s ambitions extend beyond Google’s prize money. If their mission goes according to plan, the MX-1 spacecraft will carry commercial payloads in addition to the hardware required to satisfy Google’s requirements.

Eventually, the company aims to run a full-fledged lunar delivery service. "We envision bringing precious resources, metals, and Moon rocks back to Earth," said co-founder and chairman Naveen Jain in a statement.

The idea of space mining is nothing new. The moon’s helium 3 reserves would be valuable fuel for future fusion reactors, and its ice could be melted for water or split for hydrogen to power spacecraft. Another company, Planetary Resources, has set its sights on harvesting metals and water from asteroids. It estimates that water alone, which it calls “the oil of space”, could become a .

But all of this fervor surrounding celestial resources raises the question, who owns space? According to the UN, everyone and no one. The Outer Space Treaty of 1966 established guidelines governing the extraterrestrial activities of states. Among them, no weapons, no claiming territory, and all enterprises should be carried out in peace for the .

It’s those last two points that are proving controversial. To pave the way for Moon Express, Planetary Resources, SpaceX, and a growing legion of private space ventures, the US government passed the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act in 2015.

The law justified the mining of the moon and asteroids by granting companies the right to own and sell resources extracted from space objects, but not the objects themselves. Apparently, in space, possession (and access) is ten-tenths of the law. Some argue that this approach , if not the letter, of the Outer Space Treaty’s provision that space should benefit all countries.

Indeed, as more companies and countries start to participate in what could become a scramble for space, demand for a more robust legal framework will grow. In anticipation, universities are already offering programs in space law.

Until then, Moon Express and its X Prize competitors will continue their race to usher in a new era of exploration and development. As Richards put it, “We are now free to set sail as explorers to Earth’s eighth continent, the Moon, seeking new knowledge and resources to expand Earth’s economic sphere for the benefit of all humanity.”