GMO could bring back the American chestnut. But should it?

Loading...

| Syracuse, N.Y.

Edward Kashmer has fond memories of the American chestnut tree. As a child in the 1930s in western Pennsylvania, he and his playmates would make use of the small, sweet nuts produced by the trees.

“We couldn’t afford golf balls,” he says. “So we used chestnuts.”

Today, on the wall of his apartment in a retirement community in Jamesville, New York, is a regulator clock with an American chestnut cabinet that he says he carved in the 1990s. Mr. Kashmer, who says he owned a woodworking business for 20 years, points out the straightness and closeness of the wood’s grain. “What makes it perfect are the wormholes,” he says indicating the pinpoints bored by insects.

Why We Wrote This

Efforts to repair damaged ecosystems often come with hard choices about what kinds of intervention into nature are permissible and what should be considered off limits.

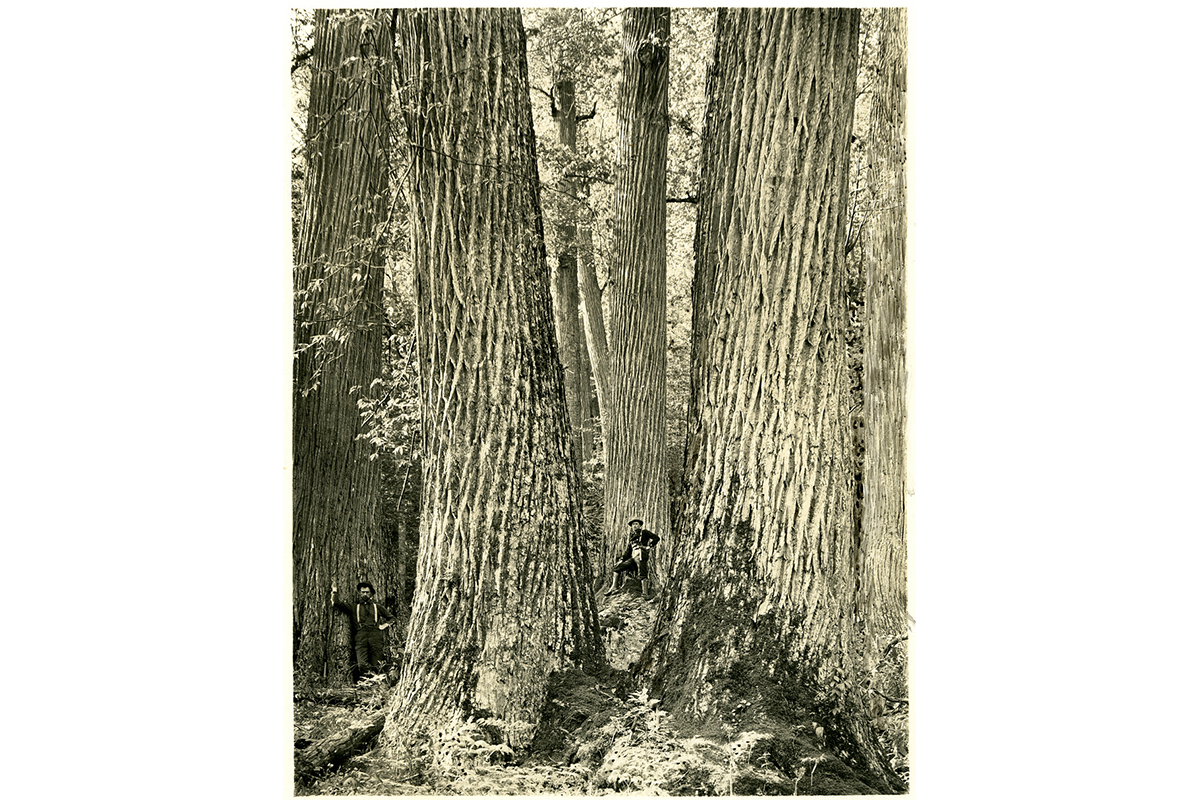

American chestnut trees were once plentiful from Maine to Georgia. But around 1904, a fungus clinging to a Japanese chestnut tree came to New York City. The spores spread on the wind, and within a few decades the American chestnut was all but wiped out. Most memories of mature, living trees reside only in the minds of people in their 80s and 90s.

But less than five miles away from Mr. Kashmer’s retirement community, scientists are working to restore this icon of America’s rustic past. Using a gene taken from wheat, scientists have successfully bred a lineage of American chestnut trees that tolerates the blight,��and they hope to someday release it into the wild.

If approved by federal agencies, it would be the first time a genetically modified organism would be intentionally set free into nature to reproduce. To some environmentalists, including two prominent American chestnut restoration activists in Massachusetts, this is a bridge too far.����

But to biologist��William Powell, one of a duo who led the project, the addition of the wheat gene represents the smallest possible human intervention that could restore the species.��

Standing not far from a grove of transgenic American chestnut saplings at a USDA-permitted research station in Syracuse, Dr. Powell, a professor at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF), hopes his project might help redeem the Empire State.

“New York is where the blight started,” he says.��“And here is where I’m hoping it’ll stop.”

An ‘almost perfect tree’

Dr. Powell calls the American chestnut an “almost perfect tree.” It grows remarkably quickly, and, when planted near other trees, remarkably straight. The wood is easy to split and hard to rot, and from the Colonial era onward, Americans used it for fences, railroad ties, furniture, cradles, caskets, and anything else they wanted to last.

Chestnut trees, which once accounted for a fourth of all hardwood trees in some eastern forests, played a key role in the southern Appalachian economy. Free-range hogs would forage on the chestnuts. People could collect chestnuts to pay off grocery debts or trade them for shoes.

“It has so many values to it,” says Dr. Powell. “Almost everything eats chestnuts.”

That began to change in 1904, when chestnut trees at the Bronx Zoo started dying. The culprit was soon discovered to be Cryphonectria parasitica, a fungus native to Asia to which the American chestnut lacks any natural immunity.

The blight spread from New York, devastating eastern forests. By 1945, the year Mel Tormé and Bob Wells wrote about roasting chestnuts on an open fire, some 4 billion trees were gone.

In southern Appalachia, the blight destroyed a way of life. Striking during the Great Depression, it ended many people’s ability to live off the land, driving them into wage labor, often in the coal mines.

In a sense, both the trees and those who lived off of them were forced underground. Because microbes in the soil kill the fungus, many of the trees’ root systems survived, awaiting the day when the blight would no longer afflict them.

‘A little bit of an art’

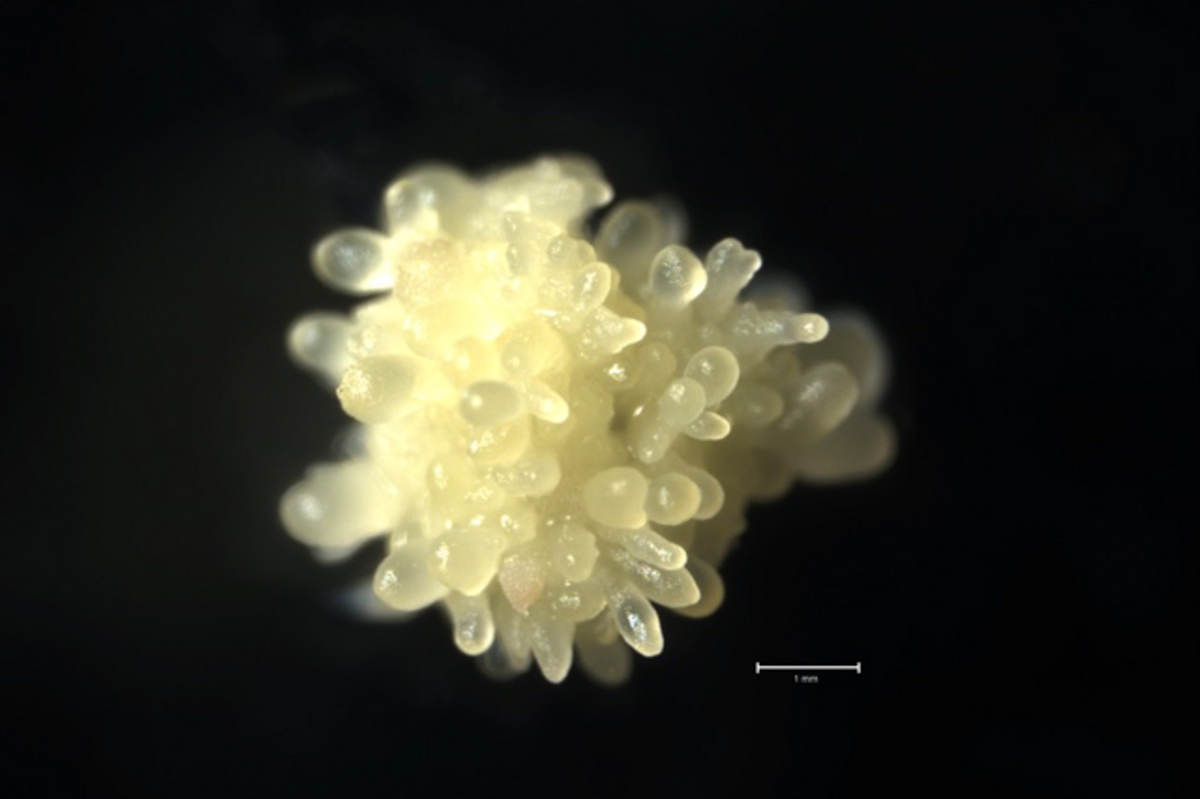

Through a microscope, the chestnut embryos at the lab for the American Chestnut Research & Restoration Project at SUNY ESF’s Illick Hall look like Israeli couscous: clusters of tiny pearl-like spheres. The embryos are the progenitors of Darling 58, chestnut trees whose genome Dr. Powell and his colleague, Charles Maynard, spent decades learning to tweak by adding a single gene from bread wheat.

At the lab, the trees are reproduced asexually, first by cracking open the nut and removing the embryos from the tip of the nut. These embryos are cleaned and then placed in a petri dish containing a nutrient-rich gel, where, if all goes well, they will multiply. Like growing plants, they are repotted into new petri dishes with new nutrients every few weeks as they grow and, eventually, sprout.

“We try to replicate what goes on inside the nut,” says Linda McGuigan, a researcher at the lab. “It’s a little bit of an art.”

When the transgenic trees are crossbred with American chestnuts, only about half of the plants will carry the gene. “Because it’s only on one chromosome, you would have half the [offspring] being transformed,” says Sara Fitzsimmons, a Penn State forest researcher and the director of Restoration for the American Chestnut Foundation, a nonprofit that sponsors the work at ESF.

At a greenhouse on the top floor, the leaves from transgenic chestnut saplings bear holes from hole-punchers used to collect leaf samples for testing. Those shown to have the gene will eventually go on for further testing, perhaps at the nearby research station where, enclosed in deer fencing, healthy American chestnut trees are growing in upstate New York again.

An ‘irreversible experiment’

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Environmental Protection Agency will need to sign off on the transgenic trees before they are released into the wild to reproduce, a process that could take up to three years. Dr. Powell says that he hopes to have approval by 2020.

But not all environmentalists champion the work.��Today a group of activists opposed to genetically engineered trees released a white paper arguing that the unknown risks are far too great.

“The release of GE AC into forests would be a massive and irreversible experiment,” reads the paper, authored by��Rachel Smolker of Biofuelwatch and Anne Petermann of the Global Justice Ecology Project.

The authors argue that the project at ESF represents a “Trojan Horse” that would open the gates for regulatory approval for genetically engineering trees for profit.

Doria Gordon, a senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund,��agrees that caution is warranted when dealing with transgenic organisms. But she sees little evidence for the Trojan horse argument. “Those floodgates,” she says, “already were open with the extensive use of genetically modified crop species.”

In March, two board members of the Massachusetts and Rhode Island chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation, one of them the chapter president, resigned in protest over the national organization’s support for the technology.��

“I’m not against genetic engineering,” says Lois Breault-Melican, who walked away from what would have been her fifth year as president. “That’s not the problem.”

To Ms. Breault-Melican, who has long promoted backcross breeding, which involves hybridizing the American chestnut with its more blight-tolerant Asian and European relatives, the transgenic trees are unnecessary.

“There’s no hurry to do this,” she says. “The backcross breeding program is working the way that it is supposed to work. When we joined, they realistically said to us that this will probably be a 100-year project.”

Dr. Powell insists that time is of the essence. While the trees’ roots can survive the blight, they cannot live forever. Those roots are crucial for a healthy restored population. “Every year that passes, we lose some genetic diversity,” he says. “We don’t want a monoculture.”

But it’s the trees longevity that also concerns Ms. Breault-Melican. “When they genetically engineer a corn plant, that plant will live for a year. But if you get a genetically engineered tree, well, American chestnut trees live up to 200 years.”

“It’s the unknown risks of the GE tree, especially down the road,” she says.

Ms. Fitzsimmons at Penn State says there are no guarantees that any single approach will prove fruitful. “You can’t say with certainty that this gene will, no matter what, restore the species.”

All you can say, she says, “is ‘Let’s take multiple approaches to create a more robust population that can persist into the future, that will give us a better chance.’”

At the American Chestnut Foundation, those approaches take the form of the three B’s: conventional breeding, biocontrol to keep the fungus away from the trees, and biotechnology.

Dr. Gordon at the Environmental Defense Fund��agrees that a multipronged approach is needed in a world where forests are under assault from climate change, invasive species, and other environmental perils. “We are going to need every tool in the toolbox to make sure that we have resilient natural and human systems into the future.”

“But,” she says, “we must be precautionary in how we deploy novel gene types into the environment.”

“I am sympathetic to the individual reactions of people and their belief systems to these kinds of technologies,” she says. “We have to have a process for weighing those concerns against the other risks and benefits of deploying genotypes that may increase the resilience of our land and water systems.”

This article has been updated to clarify that the national and regional chapters of the American Chestnut Foundation are distinct entities.��The regional chapter does not hold a position on genetic modification.