Schiaparelli's descent to Mars: How did the ESA pick this landing spot?

Loading...

On Sunday, The Schiaparelli began its daring descent to the Red Planet.

The lander, developed by the European Space Agency (ESA) in collaboration with Russia’s Roscosmos, detached from the ExoMars spacecraft on Sunday morning. As it separates from the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), Schiaparelli begins  a three-day journey to the Martian surface.

The landing could represent a new beginning of sorts. If successful, Schiaparelli will become the first European lander on Mars, laying the groundwork for future research. Looked at another way, the impact will conclude of years of exhaustive planning around a single question: Where will we land?

ExoMars is a $1.4 billion enterprise – to justify that cost, researchers must maximize the mission’s scientific returns. That’s why location is everything. Schiaparelli will target a generalized landing site – relatively flat, ellipse-shaped and about 60 miles across – on Mars’s Meridiani Planum.

“Among the highest-priority sites are those with subaqueous sediments or hydrothermal deposits,” wrote Boston University researchers Bradley Thomson and Farouk El-Baz in . “The ExoMars rover will have the capability to drill up to 2 meters into the subsurface and will search for evidence of organics from an environment that is shielded from surface radiation.”

The topology of a landing site is also essential. Crewed spacecraft are capable of making landings on more complex geographical locations, but the communication delay between Earth and Mars means that uncrewed rovers aren’t able to make on-the-fly adjustments. Probes are more likely to survive impact with flat ground than with uneven surfaces.

Energy efficiency is also a key consideration. The TGO, along with future ESA rovers, are powered largely by solar panel arrays. To maximize sunlight exposure, many lander missions choose to touch down close to the planet’s equator. The Meridiani Planum, which was also the 2004 landing site for NASA’s Opportunity rover, is located just 2 degrees south of Mars’ equator.

The ESA will from mission control as the lander begins its descent.

єЈЅЗґуЙс’s Weston Williams reported:

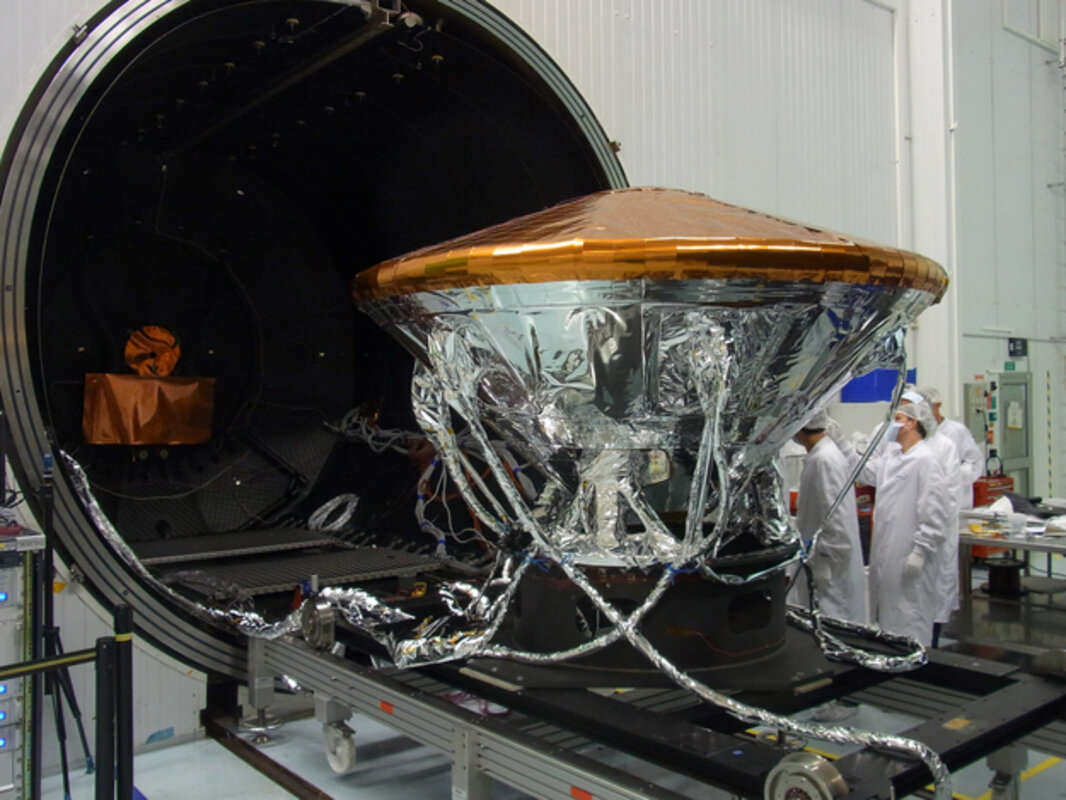

Essentially, Schiaparelli will be launched with a traditional heat shield and parachute combo, but the thin atmosphere will not be enough to slow the [Entry, Descent and Landing Demonstrator] down enough for a safe landing with those methods. Once the parachute slows the descent as much as it can, the hydrazine rockets will slow it the rest of the way before cutting out two meters from the surface. From there, the probe will drop, with a crushable layer protecting the rest of the probe from harm.

If the lander survives the impact, it will test a series of technologies for future ESA rovers. Schiaparelli isn’t solar powered, so it will perform only for a few days before its batteries run dry.

The agencies hope to discover further evidence of methane on Mars’ rocky surface. Much of Earth’s methane is produced by living organisms, so trace methane on the Red Planet could be evidence of previous life. Geological phenomena, however, can also produce the rare gas.

The lander was named for Giovanni Schiaparelli, the Italian astronomerВ who made the first crude maps of Mars in the 19th century.