After the Large Hadron Collider, an Even Larger Hadron Collider?

Loading...

Even though the world's most powerful atom-smasher was completed just six years ago, its makers are already looking ahead to the next one.

CERN, the world's largest particle physics lab, famous for developing the World Wide Web and, more recently, discovering the Higgs boson, wants to build a circular atom smasher with a circumference of 49 to 62 miles – three or four times the circumference of its record-breaking Large Hadron Collider (LHC) – and collision energy of up to 100 TeV.

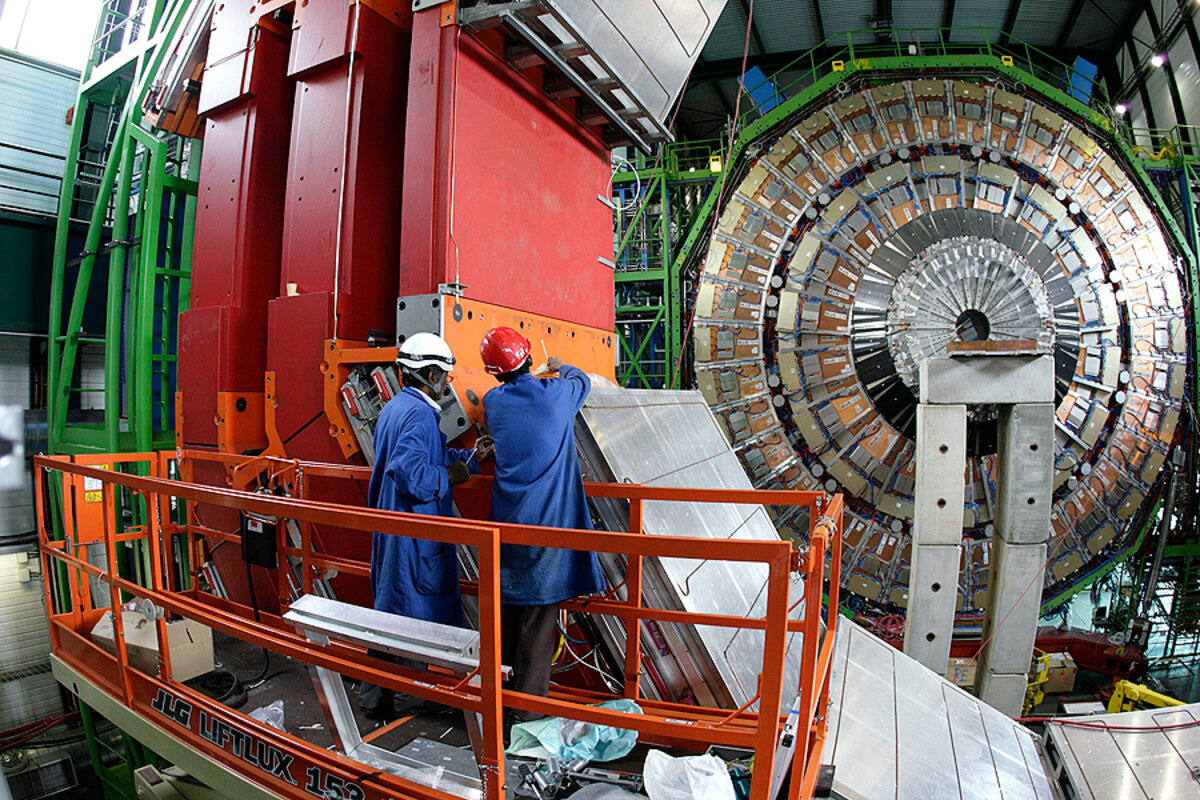

The LHC is a ring of superconducting magnets in a 16.5-mile circular tunnel buried 100 meters below the Swiss/French border.

"A worthy successor to the LHC, whose collision energies will reach 14 TeV, such an accelerator would allow particle physicists to push back the boundaries of knowledge even further," CERN announced in a press release.

In the early 1980s, while the Large Electron-Positron (LEP) collider was being designed and built, scientists at CERN were already thinking about the LHC. It took 25 years for the plan to take shape and for LHC to become a reality. The LHC finally started its operations in 2008.

"Even though the LHC programme is already well defined for the next two decades, ," CERN said in a statement.

“We need to sow the seeds of tomorrow’s technologies today, so that we are ready to take decisions in a few years’ time,” said Frédérick Bordry, CERN’s Director for Accelerators and Technology.

This collider is part of the Future Circular Colliders (FCC), a five-year international study program that focuses especially on studies for a hadron collider, like the LHC, capable of reaching collision energies of 100 TeV.

But scientists are keeping their options open. The FCC will run alongside another study of the Compact Linear Collider, or “CLIC” which has been underway for a few years now. The CLIS could be another post-LHC option for CERN.

"The aim of the CLIC study is to investigate the potential of a linear collider based on a novel accelerating technology," CERN said.

In 2012, CERN scientists announced that they had observed particles consistent with the Higgs boson – an elusive particle that could explain how other elementary particles gain their mass.

Later on, CERN confirmed that the particle observed after experiments at CERN's Large Hadron Collider was a Higgs boson, but "," according to CERN. Scientists at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory near Chicago had collected and analyzed data that pointed toward the existence of

“We still know very little about the Higgs boson, and our search for dark matter and supersymmetry continues. The forthcoming results from the LHC will be crucial in showing us which research paths to follow in the future and what will be the most suitable type of accelerator to answer the new questions that will soon be asked,” said Sergio Bertolucci, Director for Research and Computing at CERN.